Solar tax equity structures

The US government offers two tax benefits for renewable energy projects: an investment tax credit and depreciation. They amount to at least 44¢ per dollar of capital cost for the typical solar project.

Few developers can use them efficiently. Therefore, finding value for them is the core financing strategy for most solar companies.

Tax equity covers 35% of the cost of a typical solar project, plus or minus 5%. The solar company must cover the rest of the project cost with some combination of debt and equity.

Most debt is back-levered debt, meaning it sits behind the tax equity in terms of priority of repayment. Such debt is cheaper than tax equity. Competitive pressures mean back-levered lenders are not charging higher interest rates than they would charge for senior debt at the project level.

More than 40 tax equity investors invested in the solar market in the 18 months before COVID-19 hit. Roughly 50% of tax equity last year was supplied by just two large banks: JPMorgan and Bank of America. Renewable energy tax equity was a $17 to $18 billion market in 2020. It had been expected to hit $20 billion in 2021 before supply-chain difficulties began causing projects to slip into 2022.

Tax equity yields this past year have been mainly in the 6% to 8% range. After this yield is reached, the investor's economic interest in the project drops usually to 5%. Tax equity investors charge structuring and unused commitment fees and price to a second all-in yield 50 to 100 basis points higher to be reached in many transactions around year 20 to 25.

Most tax equity investors are banks and insurance companies for whom a 6% to 8% yield is attractive compared to alternative uses of money, like making loans. A theory that internet retailers who have made huge profits since the start of the pandemic would be future sources of tax equity proved unfounded, as such companies can earn higher returns by reinvesting earnings in their own businesses.

Individuals, S corporations and closely-held C corporations, meaning corporations with five or fewer individuals owning more than half the stock, have a harder time than large companies acting as tax equity investors. They must thread passive loss and at-risk rules that make it harder for them to use tax benefits from such investments.

There are three main solar tax equity structures with two significant variations. The three are partnership flips, inverted leases and sale-leasebacks.

Each of the tax equity structures raises a different amount of tax equity, allocates risk differently and imposes a deadline on when the tax equity investor must fund its investment.

About 80% of solar tax equity deals are structured currently as partnership flips.

Solar companies have been restricted since 2006 to claiming an investment tax credit that is a percentage of the amount the owner paid for the project and is claimed entirely in the year the project is first put in service. The "Build Back Better" plan being debated in Congress would allow production tax credits to be claimed instead. These are tax credits of at least $25 a megawatt hour that are claimed over 10 years on the electricity output. Partnership flips are the only structure that works for projects on which production tax credits will be claimed.

Partnership Flips

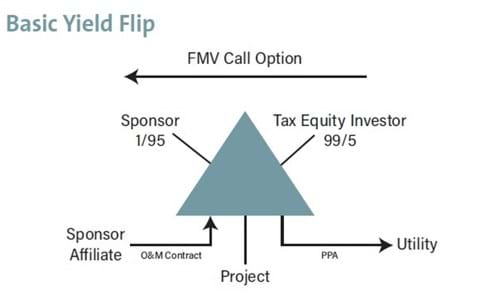

A partnership flip is a simple concept. A solar company brings in a tax equity investor as a partner to own a renewable energy project together. Partnerships do not pay income taxes; rather, any income earned, loss suffered and tax credits to which the partnership is entitled are reported by the partners.

The partnership allocates taxable income, loss and tax credits 99% to the tax equity investor until the investor reaches a target yield, after which its share of income and loss drops to 5% and the solar company has an option to buy the investor's interest. Cash may be distributed in a different ratio before the flip.

Any purchase after the flip is usually for fair market value determined at time of purchase. The Internal Revenue Service allows fixed-price purchase options as long as the price is a good faith estimate of what the investor's post-flip interest will be worth when the option can be exercised.

The IRS issued guidelines for partnership flip transactions in 2007. The guidelines provide a "safe harbor" for transactions that conform to them. Most do. The IRS said in 2015 that the guidelines were written with wind projects in mind and are not a safe harbor for solar transactions. (For more detail, see "The Partnership Flip Guidelines and Solar" in the July 2015 NewsWire.)

The central tension in flip deals is what label to put on the tax equity investor. The investor must be a real partner to be able to share in tax benefits at the partnership level as opposed to a lender earning a largely fixed return by an outside maturity date or a bare purchaser of tax benefits. Federal tax benefits may not be bought and sold.

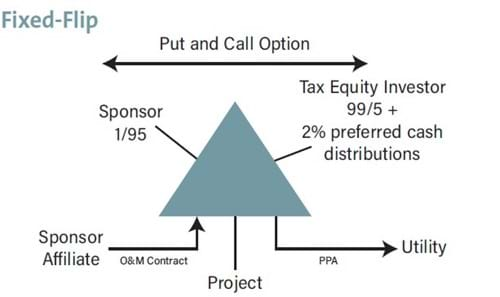

There are two main variations in flip structures. In addition to the yield-based flip, there is also a fixed-flip structure that is offered by a small subset of tax equity investors and that leaves as much cash as possible for the solar company.

The tax equity investor in a fixed-flip transaction usually receives annual preferred cash distributions—ahead of any other distributions—equal to 2% of its tax equity investment. Almost all the remaining cash is retained by the solar company.

There are usually call and put options after the fixed-flip date. The solar company can buy the 5% post-flip interest of the investor for the fair market value at time of purchase. If it chooses not to so do, the investor can "put" its interest to the partnership usually six months later. It is important that there be a time lapse and a difference in exercise prices for the call and put.

The solar company is responsible for day-to-day management of the project. Tax equity investor consent is required for a list of "major decisions."

The tax equity investor may invest by buying an interest in the partnership from the company or by making capital contributions to the partnership. In most transactions, the solar company sells the special-purpose project company near the end of construction to the partnership as a way of stepping up the asset basis for calculating tax benefits to fair market value.

Almost all partnership flip transactions have "absorption" issues. Each partner has a "capital account" and "outside basis" that are two ways of measuring what the partner put into the deal and what it is allowed to take out in tax benefits. Most tax equity investors run out of capital account before they are able to absorb 99% of the depreciation. At that point, any remaining net tax losses shift to the solar company.

There are two ways to deal with the problem. One is by putting debt at the project or partnership level. This turns the losses into "nonrecourse deductions" that can be claimed even after the investor has run out of capital account, but at a cost to the investor of having to report an equivalent amount of "phantom" income later as the senior debt principal is repaid. (The income is "phantom" income because cash from electricity sales that the partnership might otherwise have to distributed to partners for use paying taxes on the income has gone to repay the debt principal.)

The other way to address absorption issues is for the investor to agree to make a capital contribution when the partnership liquidates to cover any deficit in its capital account. This is called a "deficit restoration obligation," or "DRO." Some tax equity investors have been willing to agree to DROs of as much as 50% to 70% of their initial tax equity investments. DRO percentages lately have been smaller. The IRS requires that certain steps be taken to show the DRO is real. (For more detail, see "Deficit Restoration Obligations" in the December 2019 NewsWire.)

In many solar deals, the income allocated to the tax equity investor drops to 67% after year 1 until the partnership turns tax positive. The sharing ratio is often restored to 99% once the partnership starts earning income.

Yield-based flips in the solar market price to reach yield in six to eight years. Fixed-flip deals flip at five to six years. Investors want at least a 2% pre-tax yield, but treat the tax credits as equivalent to cash for purposes of these calculations.

For more detail on partnership flips, see "Partnership Flips" in the February 2021 NewsWire.

Sale-Leasebacks

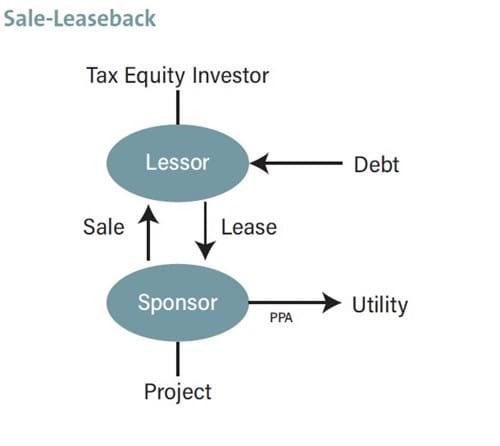

In a sale-leaseback, the solar company sells the project to a tax equity investor and leases it back.

Unlike a flip where the tax equity investor gets at most 99% of the tax benefits, all the tax benefits are transferred to the tax equity investor without complicated partnership accounting. The investor calculates them on the fair market value purchase price it pays for the project. The lessee has a gain on sale to the extent the project is worth more than it cost to build.

A flip raises 35% of the project value, plus or minus 5%. A sale-leaseback raises in theory the full fair market value, but in practice, the solar company is usually required to return 15% to 20% of the amount at inception as prepaid rent.

The prepaid rent is treated as a "section 467" loan by the solar company to the tax equity investor that is worked off over time. The solar company has to report interest on the loan as income and the tax equity investor has interest deductions to the extent it can use them under the current 30% cap on interest deductions. (For more detail, see "Cap on Interest Deductions Explained" in the August 2020 NewsWire.)

The IRS has guidelines for "leveraged" leases where the tax equity investor raises part of the purchase price by borrowing from a bank. These guidelines limit the term of the leaseback to 80% of the expected life and value of the project. If the solar company wants to keep the project at the end of the lease, the solar company must repurchase it. Any lessee purchase option cannot be at a price that makes the option reasonably likely to be exercised. There also must not be any economic compulsion for the solar company to exercise.

Sale-leasebacks remain common in the commercial and industrial and small utility-scale solar markets. They are uncommon in the rooftop market, where the deals are split currently between partnership flips and inverted leases. Rooftop companies dislike sale-leasebacks because they feel the tax equity investors pay too little at inception for the residual value after the lease ends. It frustrates them then to have to pay the full residual value to buy back the assets.

Inverted Leases

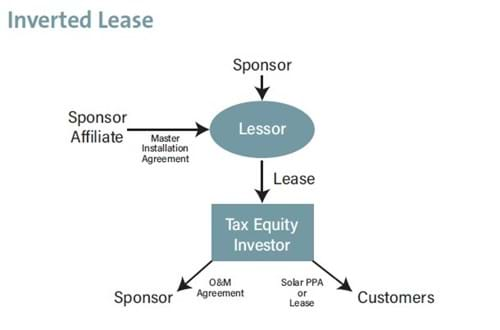

Inverted leases are used mainly in the rooftop market, although some utility-scale transactions have been done, including with debt that is effectively senior to the tax equity.

Think of a yo-yo. A solar rooftop company assigns customer agreements and leases rooftop solar systems in batches or "tranches" to a tax equity investor who collects the customer revenue and pays most of it to the solar company as rent. The solar company passes through the investment tax credit to the tax equity investor. It keeps the depreciation. The solar company takes the asset back at the end of the lease. The transactions work the same way in the utility-scale market, except that the tax equity investor is assigned a long-term power contract and then leased the solar project.

Solar companies like inverted leases because they get the asset back without having to pay for it, and the investment credit is calculated on the fair market value of the solar equipment rather than its cost. Unlike a sale-leaseback, the step up in asset basis does not come at a cost to the solar company of a tax on a commensurate gain.

There are no IRS guidelines for inverted leases, unlike the other two structures. However, the structure is common in transactions involving tax credits for rehabilitating historic buildings, and the IRS acknowledged it in guidelines in early 2014 to unfreeze the historic tax credit market after a US appeals struck down an aggressive form of the structure in a case called Historic Boardwalk. (For more details, see "IRS Sheds Light on New Tax Equity Guidelines" in the January 2014 NewsWire.)

The tax equity investor must have upside potential and downside risk to be considered a real lessee. Some tax counsel like to see a "merchant tail," meaning a period after the customer agreements or power contract ends when the lessee is exposed to market risk on electricity sales. Others focus on the amount of prepaid rent paid by the lessee and want to see at least a 20% rent prepayment on the theory that the more skin the tax equity investor has in the game, the more likely the lease will be respected.

Some big-four accounting firms treat the structure as a secured loan by the tax equity investor to the solar company, rather than a real lease, for book purposes.

Inverted leases raise the least amount of tax equity. The central challenge in inverted leases is how the capital raised by the structure moves from the tax equity investor to the solar company.

In the conservative form, the tax equity investor contributes the tax equity investment to a lessee partnership that is owned 1% by the solar company and 99% by the tax equity investor, and the capital contribution moves to the lessor (i.e., the solar company) as prepaid rent.

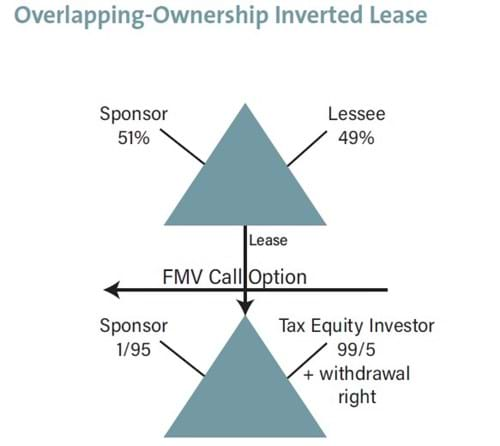

In an overlapping ownership structure, the tax equity investor makes a capital contribution to the lessee partnership, and the lessee partnership contributes it to a lessor partnership that is owned 51% by the solar company and 49% by the lessee partnership. This structure raises more tax equity because the tax equity investor claims not only the investment tax credit, but also 49% of the depreciation.

For more detail on inverted leases, see "Inverted Leases" in the June 2017 NewsWire.

Structures Compared

The three structures vary in terms of the amount of capital raised, risk allocation and the timing of when the tax equity investor must invest. The solar company must turn to other sources of capital (debt and equity) to raise the rest of the project cost.

Focusing on risks, in a sale-leaseback, the solar company has a hell-or-high-water obligation to pay rent and must indemnify the tax equity investor for loss of tax benefits and any acceleration of rental income due to a solar company breach of a representation or covenant. In a flip, the tax equity investor's return turns on how well the project performs. The tax equity investor's protection is it sits on the project at a 99% level until it reaches a target yield. The risk allocation in inverted leases is closer to the allocation in sale-leasebacks.

The principal business risks in any transaction are weather, technology, vacancy risk, curtailment risk, electricity basis risk and offtaker credit.

Turning to timing, the tax equity investor must be a partner in a flip deal before the project is placed in service.

In most solar transactions, the tax equity investor contributes 20% of its total investment after the project reaches mechanical completion, but before it is placed in service, contributes the rest after construction has been completed. Inverted leases must be done before assets go into service. A sale-leaseback can be done up to three months after the asset is put in service.

In many deals, the tax equity investor has an unwind right to get back its 20% investment if the conditions to make the remaining 80% investment are not met: for example, because project completion is delayed beyond the outside commitment date for the tax equity investment. Such unwinds take various forms depending on the preference of the tax equity counsel.

Risks

A central challenge in all solar deals is how to get a step up in tax basis so that the tax benefits are calculated on the fair market value of the project rather than its cost. The market has been watching two key cases moving through the courts. A wind developer lost two key developer fee cases (California Ridge and Bishop's Hill) in 2020 before a US court of appeals. (For more detail, see "California Ridge: Developer Fees Struck Down—Again" in the May 2020 NewsWire.) A basis allocation case (Alta Wind) is headed to retrial in late 2022 or 2023, and another case (Desert Sunlight) that may also shed light on basis issues is headed to trial in 2022.

Tax basis risk tends to be borne by the solar company, although this has been true only since 2010. Tax risks about which the solar company has special insight are borne by the solar company. An example is whether the project was under construction in time to qualify for tax benefits. Tax risks into which both the solar company and tax equity investor have equal insight are borne by the tax equity investor: for example, whether the structure works to transfer tax benefits to the investor. Risks over which neither has special insight are jump balls. An example is change-in-law risk.

Many tax equity investors are limiting the percentage markup they are willing to see in fair market value above cost. Some are requiring tax insurance to cover basis risk. Premiums on tax insurance run generally 2.5% to 3.5% of the maximum potential payout.

Cash sweeps are another source of tension in deals. Solar companies want to retain enough cash to cover debt service on back-levered debt. Many tax equity investors agree to limit sweeps to 50% to 75% of cash or, in some cases, to prevent the sweep from reaching cash to cover principal and interest on the debt.

In most deals, a section 6226 "push-out election" is made to address the risk of a back tax assessment at the partnership level. The IRS audits partnerships, but has grown tired of chasing partners for their shares of any back tax assessment. Congress gave it the right starting in 2018 to collect back taxes from partnerships directly. A push-out election is an election to push out any back tax liability to persons who were partners in the year under audit. If such an election is made, the partners must pay 2% extra interest on the back tax liability.

Property taxes are an ever-present issue in transactions involving solar equipment in California. Any change in ownership of solar equipment after initial installation will trigger a property tax reassessment. A new bill signed at the end of September (SB 267) makes clear that the initial investment by the tax equity investor and later flip are not considered changes in ownership. (For more detail, see "Partnership Flips and California Property Taxes" in the December 2021 NewsWire.)

Higher Tax Credits

The "Build Back Better" plan that passed the US House of Representatives just before Thanksgiving would restore renewable energy tax credits to the full level and extend deadlines to qualify. It would also provide a direct-pay option to receive cash payments from the IRS in place of tax credits.

Any project in a census tract where a coal mine has closed since 1999 or where a coal-fired generating "unit" has been retired since 2009, or in an adjacent census tract, qualifies potentially for an extra 10% investment tax credit or 1.1 times the production tax credits for which the project would otherwise qualify.

The restored tax credits will come with two bits of fine print.

The same Davis-Bacon wages that the US government pays on federal construction projects must be paid to mechanics and laborers during construction and for the five or 10 years after construction on alterations and repairs. Apprentices must be used on 10% to 15% of total labor hours.

The wage and apprentice requirements do not apply to any project on which construction starts no later than 59 days after the IRS issues guidance.

The other fine print is all steel, iron and manufactured products must be made in the United States.

The domestic content requirement is a carrot and a stick. The carrot is up to an extra 10% investment tax credit or 1.1 times the production tax credits for which the project would otherwise qualify. The stick is inability to receive a full direct cash payment for projects that start construction in 2024 or later.