Partnership flips

Partnership flips are used to raise tax equity in the US renewable energy market. They are not the only structure for doing so, but they are the most common, and they are the only way to raise tax equity for wind farms and other projects on which production tax credits will be claimed.

This article describes how the structure works and current issues that are taking up time in partnership flip transactions.

The US government offers two tax benefits: a tax credit and depreciation. They amount to 44¢ to 49¢ per dollar of capital cost for the typical wind or solar project that was under construction in time to qualify for tax credits at the full rate. Few developers can use the tax benefits efficiently. Therefore, finding value for them is the core financing strategy for many US renewable energy companies.

Tax equity accounts for 65% of the capital stack for a typical wind farm, plus or minus 10%. It accounts for 35% for a typical solar project, plus or minus 5%. The percentages should increase if, as expected, Congress increases the corporate tax rate from the current 21% to between 25% and 28%.

The developer must fill in the rest of the capital stack with debt or equity.

More than 40 tax equity investors did transactions in the 18 months before the COVID-19 lockdowns started in March 2020. Many developers had a hard time finding tax equity during 2020, and 2021 is expected to remain a challenging year. Competition from $3-to-$6 billion offshore wind projects and from a potentially rapidly growing market for carbon capture projects that qualify for section 45Q tax credits is expected to add to the challenges.

Renewable energy tax equity was a $12 to $13 billion market in 2019. It was $17 to $18 billion in 2020. Two banks – JPMorgan and Bank of America – accounted in both years for more than half the market.

The renewable energy trade associations are urging Congress to allow owners of new renewable energy projects to apply for refunds from the IRS for the tax credits. Any such change would be part of a clean energy and infrastructure bill that is expected to move through Congress by early fall. If such a provision is enacted, developers are still likely to turn to the tax equity market for financing as they did during the period 2009 through 2016 when the US Treasury was paying the cash value of the tax credits as an Obama economic stimulus measure. Tax equity will still be needed to monetize tax depreciation on the projects, and the tax equity market acts as a source of bridge financing for the tax credits until the cash payments are received. Several large banks came back into the tax equity market during the Treasury cash grant era despite lacking tax capacity.

Simple Concept

Partnership flips are a simple concept. Tax benefits can only be claimed by the owner of a project. Partnerships offer flexibility in how economic returns can be shared by the partners. A developer finds an investor who can use the tax benefits. The two of them own the project as partners through a partnership.

All wind deals and about 80% of solar deals are yield-based flip transactions.

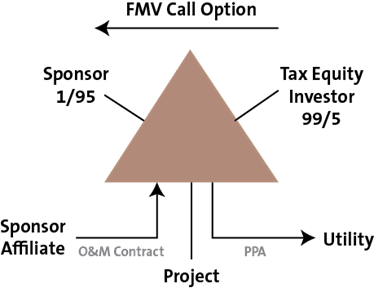

In the typical such transaction, the partnership allocates 99% of income, loss and tax credits to the tax equity investor until it reaches a target yield. Cash is shared in a different ratio. After the yield is reached, the investor’s share of everything drops to 5% and the developer has an option to buy the investor’s remaining interest.

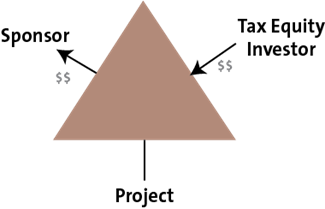

The typical structure is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Basic Yield Flip

Developers like partnership flips because they get back 95% of the project without having to pay anything for it.

In some deals, the investor takes as little as 2.5% of the cash after the flip, but this is uncommon.

The sponsor call option is usually for fair market value, although the IRS allows a fixed price that is a good faith estimate at inception of what the value will be when the option is exercised. Some developers require the investor to pay enough to avoid a book loss on sale. Sometimes the option can be exercised before the flip, but not before five years have run after the project is placed in service. Any option before the flip must pay the investor enough at a minimum to get the investor to its target yield.

The developer retains day-to-day control over the project. A list of major decisions requires consent from the tax equity investor. In some deals, the list is shorter after the flip.

Many investors use hypothetical liquidation book value, or “HLBV,” accounting to account for their investments. This requires tracking what the investor would receive at each year end if the partnership liquidated. The difference in amount from one year to the next is added or subtracted from earnings.

The Internal Revenue Service published guidelines in 2007 for partnership flip transactions. The guidelines are in Revenue Procedure 2007-65. Some revisions were made two years later in Announcement 2009-69. Most transactions remain within the guidelines.

The individual guidelines that are most likely to come into play are that the tax equity investor must retain at least a 4.95% residual interest after the flip, the flip cannot occur more quickly than five years after the project goes into service, any option to buy the investor’s interest must be for fair market value or a fixed price that is a good-faith estimate at inception of what the fair market value will be at time of exercise, the investor must make at least 20% of its total investment before the project is put in service, and the investor cannot have a “put” to require the sponsor to purchase its interest.

The guidelines bar guarantees of production tax credits by anyone, including third parties, and the developer, turbine supplier and electricity offtaker cannot guarantee the output for the investor.

Most investors want to see at least a 2% pre-tax or cash-on-cash yield. The market treats tax credits as equivalent to cash for this purpose.

The IRS said in an internal memo released in June 2015 that the flip guidelines do not apply to solar projects or other projects on which investment tax credits are claimed. The memo said to apply general partnership principles to test whether the investor is really a partner. It is CCA 201524024. (For more detail, see “The Partnership Flip Guidelines and Solar” in the July 2015 NewsWire.)

The investor must not walk so close to the line as to be considered a lender or a bare purchaser of tax benefits. A lender advances money for a promise to repay the advance plus a return by a fixed maturity date.

Variations

There are several variations in forms of partnership flip transactions.

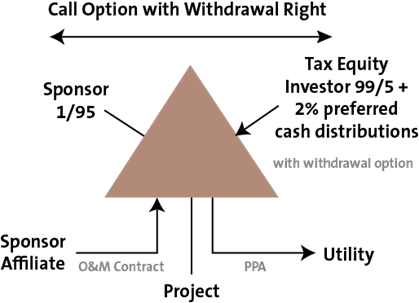

At least one major investor uses a fixed or time-based flip structure. The investor flips to a 5% interest on a fixed date, usually after five to five-and-a-half years. The developer has a call option. The tax equity investor has a withdrawal right six months to a year later if the call is not exercised.

The investor in a fixed-flip transaction receives preferred cash distributions each year equal to 2% of its original investment and some percentage of remaining cash. Developers like this structure because it lets them retain as much cash as possible. Developers would rather borrow against future cash flow at a lower debt rate than a tax equity yield.

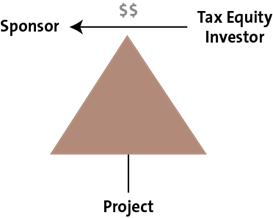

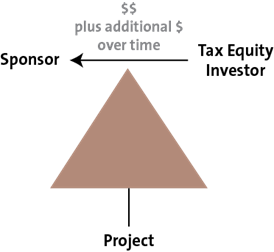

Figure 2: Fixed Flip

An area of tension in fixed-flip transactions is how quickly the partnership must pay the market value of the investor’s interest after it withdraws from the partnership. Most deal documents give the partnership two years. The withdrawal amount is paid out of partnership cash flow. If the full price is not paid within two years, then the investor can take the project. This can also create tension with any back-levered lenders who have made a loan to the developer against its expected cash distributions from the partnership.

Another source of tension is the developer ends up with a negative capital account because it keeps most of the cash. Many tax equity investors now require the developer to agree to put cash back into the partnership if the developer still has a negative capital account when the partnership liquidates.

Another common variation on the standard flip is a pay-go structure used in wind and geothermal deals with production tax credits. The investor makes 75% of its investment at inception or as a fixed amount over time, and the other 25% is tied to production tax credits the investor is allocated each year. The IRS flip guidelines limit the amount of investment that can be tied to output or tax credits to 25%. Investors were originally not keen on pay-go structures because they preferred to earn a return on the full investment from inception. However, they have gained in popularity as a way to mitigate operating risk and the risk that the tax law will change.

Most uses of the pay-go structure lately have been as a way for sponsors to get additional value for remaining production tax credits after the investor has already reached the flip yield. The pay-go payments are made in the post-flip period from the flip date through the end of the 10-year period for claiming production tax credits.

Absorption Problem

Almost all partnership flip transactions have an “absorption” problem. Each partner has a “capital account” and an “outside basis.” These are two ways of tracking what a partner put into the partnership and is allowed to take out.

Once the investor’s capital account hits zero, then its remaining share of tax losses shifts to the developer.

Once its outside basis hits zero, then any further losses it is allocated end up being suspended. They can be used only against future income the investor is allocated by the partnership. Any cash it is distributed is considered an “excess cash distribution” and must be reported as capital gain.

There are two ways to deal with an inadequate capital account. One is for the investor to agree to a “deficit restoration obligation” or “DRO.” This is a promise to contribute more money to the partnership when the partnership liquidates to cover any negative capital account. On that basis, the IRS will let the investor absorb more losses. However, the investor may still have too little outside basis to absorb them immediately. Suspended losses should not count toward the flip yield until used.

The IRS will ignore a DRO if there is a “plan to circumvent or avoid” the obligation to contribute more capital. There should be “commercially reasonable provisions for enforcement and collection of the obligation,” and the partner should be required to provide documentation regarding its financial condition. The practical effect is to impose a net worth test on the sponsor to ensure that it can satisfy the DRO. (For more details, see “Tax Equity and DROs” in the October 2016 NewsWire and “Deficit Restoration Obligations” in the December 2019 NewsWire.)

DROs today can reach 50% to 70% of the tax equity investment. Falling wholesale electricity prices are forcing them to these levels. Investors who agree to DROs usually want to be allocated income as quickly as possible after the flip to reverse the deficit and to be distributed cash to cover the taxes on the additional income.

Such post-flip measures could turn the original 99% allocations to the tax equity investor into “transitory allocations” if they are reversed within five years. The IRS does not allow transitory allocations.

An investor usually places a dollar limit on the DRO to which it has agreed.

Some investors wait to see how a year went and then increase the DRO after the year ends. Partnership allocations for a year can be adjusted retroactively up to the due date for the tax return for the year (not including extensions). In most deals, once the deficit starts to contract, the cap on the DRO goes down as well.

In fixed-flip deals where the developer ends up with a negative capital account, many tax equity investors require the developer to agree to a DRO. This makes the promise that the developer will be able to keep most of the cash somewhat illusory, since the developer may have to recontribute cash to the partnership. Special measures to reverse the developer deficit are rare.

Another way to address the absorption problem is to add project-level debt. This turns part of the depreciation into “nonrecourse deductions” that can be taken by partners even after they run out of capital account. The debt also increases the investor’s outside basis.

Partners taking nonrecourse deductions must be allocated an equivalent amount of income later as the debt is repaid, thus turning the nonrecourse deductions truly into a mere timing benefit. These later allocations are called “minimum gain chargebacks.” The partnership earns revenue from selling electricity. The partners must report the income. However, the cash goes to the lender to pay debt service, leaving the partners with “phantom” income: income but no cash distributions to cover taxes on the income. The minimum gain chargebacks are allocations of this phantom income. Chargebacks are not additional income, but rather an override on how some of the income the partnership is already allocating to partners must be allocated.

Almost all debt in the market today is back-levered debt behind the tax equity in the capital stack. If there is project-level debt, then the tax equity investor will demand a higher yield and require the lender to enter into a forbearance agreement. In contrast, lenders are not charging any premium to lend on a back-levered basis due to the intense competition among banks to lend.

A tax equity investor might take other steps to make it less likely that its capital account will go negative. These include reducing its share of income and losses in a solar deal from 99% to 67% in the year after the project is placed in service and then moving back to 99% in the year the partnership starts generating taxable income or taking depreciation on the project on a straight-line basis over 12 years.

The IRS requires that a third metric called “tax capital” be tracked and reported each year starting with K-1s sent to partners in 2021 for the 2020 tax year. This is a hybrid between capital accounts and outside basis. It is a way for the IRS to identify partners who may have taxable gains to report. Negative tax capital is a sign of a potential gain. (For more detail, see “Partnership ‘Tax Capital’” in the June 2020 NewsWire.)

If not already clear, it is important to model what will happen inside the partnership. The business deal may be to allocate income, losses and tax credits 99% to the tax equity investor, but that is usually not what will actually happen. (See “Calculating How Much Tax Equity Can Be Raised” in the June 2008 NewsWire for help with how to model the deal.)

The amount of tax equity raised through a flip transaction is the present value of the discounted net benefits stream to the tax equity investor. The investor receives three benefits: tax credits, cash and tax savings from losses. It suffers one detriment: taxes have to be paid on the income it is allocated. It discounts these amounts using its target yield to a present-value number.

Putting the Structure in Place

There are three ways to put a partnership flip transaction in place.

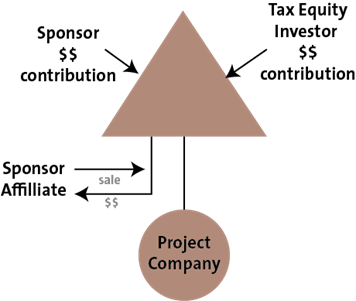

The most common approach today is a “project-company-sale model” where the developer sells the project company near the end of construction to the tax equity partnership. Both the developer and the tax equity investor contribute capital to the partnership to pay the purchase price. The project is sold for the appraised fair market value the project is expected to have at the end of construction.

In solar deals, the partnership usually pays 20% of the purchase price at mechanical completion before any part of the project is in service and the other 80% after the entire project is in service. This begs the question what happens if the conditions for the 80% payment are not met. In many deals, the partnership has a “put” to require the developer to buy the project back from the partnership for the 20% payment plus a return. However, the right to sell back lapses automatically once any part of the project has been placed in service. If the unwind right has lapsed, then the tax equity pricing model is rerun and the ratios for sharing economic returns inside the partnership between the developer and tax equity investor are adjusted because the investor will retain full ownership while having only made a fraction of its expected investment.

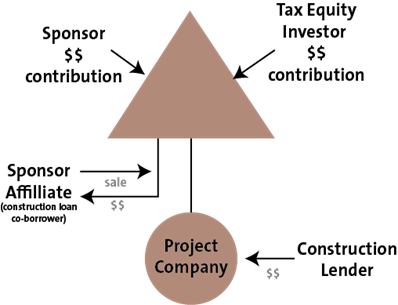

Figure 3: Project Company Sale Model

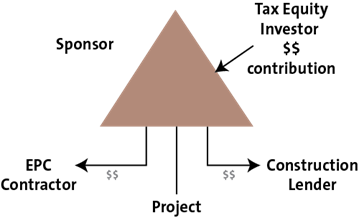

Another way to put the structure in place is a “contribution model” where the project company is already owned by the partnership and the tax equity investor makes a capital contribution to the partnership in exchange for an interest. The capital contribution may be used by the partnership to pay the EPC contractor or pay off construction debt, or it may be distributed to the developer.

Figure 4: Contribution Model

Figure 5: Contribution Model with Distribution Out

The developer may be able to pull out the tax equity raised as a tax-free return of capital. The key is to avoid having the distribution out labelled by the IRS as a “disguised sale” of the project to the partnership. It must fit in a “pre-formation expenditure” safe harbor that lets the developer be reimbursed for its capital spending on the project over the last two years.

The project cannot be worth more than 120% of the tax basis the developer has in the project when the partnership is formed to make full use of this safe harbor. If there is debt on the project when the tax equity investor makes its first capital contribution, then it will complicate the calculations to determine whether the safe harbor applies. (For a discussion about how the safe harbor works, see “Tax Triggered When Partnership Formed?” in the October 2016 NewsWire.) Any developer planning to use the safe harbor should make sure the partnership agreement says that the distribution of the tax equity contribution to the developer is a reimbursement of pre-formation expenditures within the meaning of section 1.707-4(d) of the US income tax regulations.

A third way to put the tax equity partnership in place is a “purchase model” where the tax equity investor pays the developer directly for an interest.

Figure 6: Purchase Model

In a pay-go variation on these structures, the tax equity investor pays an amount at the start to buy an interest in the project and makes additional payments over time that are a function of the output or tax credits. The contingent payments cannot be more than 25% of the total investment.

Figure 7: Pay-Go Structure

Back-Levered Tensions

There are a number of recurring issues in flip deals.

Many developers, particularly in the solar market, use back leverage to borrow against their shares of partnership cash flow. A back-levered loan is a loan to the developer against its share of cash flow from the partnership.

This creates tension between the back-levered lender and the tax equity investor, particularly over any cash sweeps at the partnership level that could divert cash needed to pay debt service on the back-levered debt. Cash sweeps may come up in two contexts. One is where an indemnity has to be paid by the developer. The other is some tax equity investors have a cash sweep to get back on track, in a deal that is falling behind, to reach the target yield on the date originally projected.

Many investors are agreeing to limit the percentage of cash to 50% to 75% that can be swept in order to mitigate the risk to the lender. Some agree not to sweep an amount of cash equal to scheduled principal and interest payments on the debt.

Change-in-control issues also come up. The lender wants a right to foreclose on the developer’s partnership interest after a debt default. The tax equity investor wants an experienced renewable energy operator as its partner and may impose net worth and experience requirements on any subsequent transferee of the interest. It would be a good idea for sponsors to get agreement from the tax equity investor on the terms of a consent by the tax equity investor to such a foreclosure and subsequent sale of the sponsor interest when the flip partnership closes, if the back-levered debt will be added later, to avoid costly and time-consuming negotiations later.

Other Recurring Issues

Developer fees are out of favor after the US Court of Federal Claims prevented Invenergy from adding $50 to $60 million developer fees to tax basis in two wind projects. The court said the fees were merely circled cash. (For more details, see “California Ridge: Developer Fees Struck Down – Again” in May 2020 NewsWire.)

Most audit activity in the solar market has been around the tax bases claimed in tax equity deals. Many tax equity investors limit the markup they are willing to allow above construction cost to 15% to 20%, although these limits are hard to enforce in practice. The IRS tends to focus on where the final basis per watt lands in relation to what it sees generally in the market.

Some tax equity investors are requiring tax insurance to cover basis risk in the residential rooftop market. Premiums on tax insurance generally run 2% to 3% of the potential payout.

Another issue in deals is how the construction debt converts into back-levered term debt. If the project company and an entity above it that sells the project company to the partnership are co-borrowers under the construction loan and the partnership buys the project company subject to the construction loan, the partnership may not be able to include the loan in tax basis if the seller remains liable for the debt. The seller should be released from the debt in order for the partnership to be able to treat it as having been assumed as part of the purchase price.

Figure 8: Project Company Sale Model

The market is wrestling currently with how to address risk of a change in tax law. Many deals require a repricing to reflect any change enacted through the end of the 117th Congress that runs through 2022. The tax equity investor does not have to fund unless any proposed adverse tax law change is reflected in the pricing. If the change is not ultimately enacted, then the investor may have to make an additional capital contribution. In some deals, the tax equity investor has a cash sweep to get back on track if any adverse tax law change delays the projected flip date by more than a year. The parties debate how far a proposed adverse tax law change needs to have advanced in Congress before the tax equity investor can use it as a reason to stop further funding.

A tax rate increase would mean more tax equity will be raised on future projects. It could delay or accelerate the flip depending on when during the life of the project it occurs. A rate increase shortly after a project is put in service would increase the value of the tax depreciation. A rate increase later in time will only increase the taxes that the tax equity investor must pay, thereby delaying the flip and increasing the cash the investor will take over time to get it to the flip yield. A higher tax rate could also ultimately increase the supply of tax equity, although how much is unclear. Tax equity yields are a function of demand and supply.

The tax equity investor bears the risk of tax law change in a fixed-flip structure. When Congress was considering reducing the corporate income tax rate in 2017, at least one fixed-flip investor asked developers for an indemnity to cover any loss in value of tax losses.

Tax equity investors have had little interest in the past in taking the 100% depreciation bonus on offer currently from the US government because they want to spread their scarce tax capacity over more deals. With the corporate tax rate expected to increase, developers are likely also to want to push depreciation into 2022 or later when it will be taken against the higher tax rate.

Investment tax credits must be shared by partners in the same ratio they share in “profits” in the year a project is put in service. The word “profits” in this context means income. The tax credits claimed by a partner will be recaptured if the ratio in which income is shared by partners leaves that partner with more than a one-third reduction in its share of profits during the first five years after the project is put in service.

Some investors reduce their share of losses to 67% after year one until the first year there are profits, when the percentage goes back to 99%. This puts less pressure on the investor capital account. The standard partnership agreement says that once a partner runs out of capital account (plus any DRO), then its remaining share of losses will be diverted automatically to the other partners. Many tax counsel believe such a loss shift will drag production tax credits in years when losses shift to the sponsor; the tax credits are shared in the same ratio that losses end up being allocated in fact in such years.

Some counsel worry that unvested investment tax credits may also be recaptured in years that losses shift if the tax equity investor ends up in fact with more than a one-third reduction in its share of losses in such a year. This position is not shared by most tax counsel. Many tax counsel are uncomfortable with a shift down that occurs quickly after assets are put in service. Thus, for example, in a deal where a solar project is put in service on December 28, many tax counsel will not want to see the tax equity investor reduce its share of profits to 67% on January 1. Most prefer to wait at least six months.

Many investors insist on holding the 99% income share for at least one full year — and sometimes for two years — of meaningful income lest the IRS say the first-year 99% allocation used to send 99% of the investment tax credit to the investor was illusory because it changed by the time there were profits.

Partnerships that generate and sell electricity must use the “inventory method of accounting.” This means they can only allocate net income or net loss. They cannot disaggregate the elements that go into the calculation of net income and loss and allocate them differently. Income and loss from rooftop solar equipment that is leased to customers can be disaggregated and allocated differently.

Taxpayers cannot claim losses on sales to related parties. This means that a partnership cannot claim net losses in years when electricity is sold to a partner. In some partnerships owning merchant power projects, the developer must put a floor under the electricity price to finance the project. Any contract between the partnership and the developer should be a swap rather than a power purchase agreement, at least during the first few years before the partnership turns tax positive.

Some developers approach inappropriate parties as tax equity investors. Passive loss and at-risk rules make it hard for individuals, S corporations and closely-held C corporations to use tax benefits on renewable energy projects. A closely-held C corporation is one where five or fewer individuals own more than half the stock. Stock held by family members is combined. An investor who is subject to the passive loss rules can use tax credits and depreciation to shelter income from other passive investments, but what is considered passive income is limited. Interest received on debt instruments and dividends received on stock are not considered passive income for this purpose.

The IRS started making back tax assessments at the partnership level in the 2018 tax year. The IRS will be able to collect back taxes directly from the partnership.

Some partnership agreements direct the managing member to elect to “opt out” of audits at the partnership level, meaning that any audits of 2018 or later tax years would be of the partners directly. Developers dislike this option because they will remain on the hook for tax indemnities, but lose the ability to handle the IRS audits that may lead to an indemnity.

In many deals, a “push-out election” is made to push out any such liability to persons who were partners during the year under audit. However, partners will have to pay 2% extra interest on the back taxes if this is done. It is important in such cases to make clear that the back taxes will be pushed out to partners in a ratio that reflects how they agreed to share the tax risks giving rise to the back tax liability.

Some recent partnership agreements leave any liability for back taxes by default at the partnership level, meaning that the economic burden to pay these taxes will fall on persons who are partners years in the future when the partnership is audited. This may be after the flip. The partners should agree to make capital contributions in a ratio that reflects how tax risks were shared by the partners and to indemnities if one of the partners is no longer a partner by the time the audit adjustment occurs. (For more detail and what options partnerships have available to them, see “US Partnerships Get a Makeover” in the November 2015 NewsWire.)

Property taxes are an ever-present issue in transactions involving solar equipment in California. Any change in ownership of solar equipment after installation will trigger a property tax reassessment. The amount could be substantial. The flip in a partnership flip transaction can trigger a reassessment if it transfers control back to the developer. A partner has control if it owns more than a 50% profits and capital interest in the partnership. The focus is on whether the developer is acquiring control rather than on whether the tax equity investor is losing it. If the tax equity investor gets control at the outset, then a reassessment will be triggered by the flip, assuming the investor has less than a 50% capital interest by the flip date. If the investor still has a 50+% capital interest, then control will transfer when the capital interest drops below 50% after the flip or, at the latest, when the developer exercises its option to buy the investor interest.

A bill has been introduced in the California legislature to prevent flips from being considered a change in control.