Guarantees for investments in emerging markets

Emerging markets offer new and exciting investment opportunities, but risks accompany the potential rewards.

Guarantees from multilateral development banks, or “MDBs,” are an invaluable risk mitigation instrument that not only helps to cover perceived government-related risks, but also facilitates access to private sources of finance.

MDBs offer two types of guarantee products: credit guarantees and risk guarantees.

Credit guarantees cover all or part of a financial obligation (usually a loan or bond) and are triggered irrespective of the cause of the default — whether political or commercial — while risk guarantees also cover all or part of a financial obligation, but are called only when the government or government-owned entity fails to meet specific obligations under project agreements to which it is a party.

This article compares and contrasts guarantees offered at the following four major MDBs or MDB groups: the World Bank Group, the Inter-American Development Bank, the Asian Development Bank, and the African Development Bank Group. It is a complement to an article in the April 2016 NewsWire that focused on the World Bank’s enhanced guarantee program for private projects.

Guarantees explained

Guarantees are a specialized form of insurance that helps a borrower leverage external resources beyond the lending capacity of MDBs. The borrower can be a national or sub-national government, state-owned enterprise or private investor.

Most MDBs prefer to offer partial coverage guarantees that do not cover the entire amount borrowed. The rationale is that a “wall-to-wall” guarantee would generate moral hazard risks, as the guaranteed investor would have little incentive to conduct its own due diligence on the viability of the proposed project and would not be subject to market scrutiny. Partial coverage guarantees on bond issues also avoid the potential pitfall of contaminating the MDB’s market for its own bonds.

There are many benefits to using MDB guarantees over traditional loan financing operations. First, MDB guarantees are intended to be flexible, both in terms of the risk covered and the tenor of the guarantee. Guarantees can target specific classes of risks (for example, expropriation, political violence, currency inconvertibility, etc.), according to the terms of the underlying guaranteed financial obligation. MDBs have high bond ratings (AAA) that enable them to provide substantial credit enhancement to sovereign and sub-sovereign obligors.

Second, multilateral guarantees help to diversify funding options and catalyze private financial flows to emerging market countries by mitigating government performance risks that private lenders are reluctant to assume. This helps to create a more stable financing structure in emerging markets. The close association of MDBs with governments and preferred creditor status can open the investor base more broadly and mobilize resources well beyond the guaranteed amount. This is the so-called ‘halo’ or ‘crowding-in’ effect.

Third, MDBs determine country allocations according to their strategic objectives in their respective portfolios, the absorption capacity of each sector and region, and other internal policies. As discussed in more detail below, some MDBs analyzed in this article recognize commitments on guarantees as counting only toward 25% of the country’s lending envelope.

Last but not least, MDB involvement in MDB-supported projects provides a strong incentive to host governments and their state-owned entities to honor their contractual obligations. A government or state-owned utility’s failure to honor commitments under an MDB-supported project could trigger reimbursement obligations under an indemnity agreement from the host government and potentially jeopardize existing and future development financing to the country.

Practical obstacles

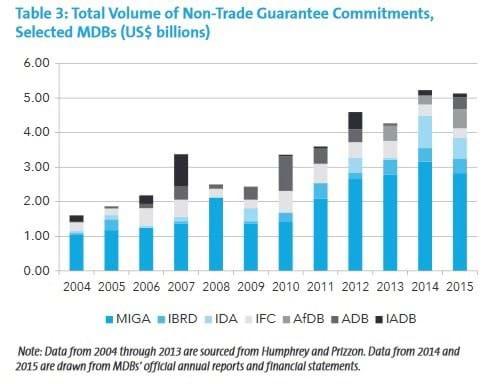

Despite these advantages, guarantees have been significantly underutilized to date compared to other forms of development financing. The MDBs considered in this article approved a total of US$40.17 billion in non-trade project guarantees between 2004 and 2015, which represents 4.4% of the total development financing over that same period.

There are several possible reasons for this apparent underutilization. MDBs face a number of major impediments to using guarantees more extensively, most notably linked to their risk capital allocation, costs, and lack of visibility.

Starting with risk capital allocation, MDBs book guarantees on the same basis as loans for the purpose of risk capital allocation. Booking guarantees 1:1 with loans discourages the use of guarantees because guarantees are treated as a loan exposure for 100% of the amount, despite the fact that guarantees are unfunded until called. The rationale is that MDBs prefer to err on the side of caution to safeguard their AAA-rated balance sheets and shareholder capital. In practice, there have been fewer guarantees called per dollar of exposure than defaults on loans. For example, there have been no calls on the World Bank’s partial risk guarantees for private or public projects since they were first issued in 1994.

Costs are another factor. An implication of the 1:1 treatment is that loans and guarantees are priced at the same level because MDB pricing is based in large part on the use of equity capital and cost of funding. MDBs rely on equity capital as money paid in to support their operations. The equity-to-loan ratio of most MDBs is in the 25% to 35% range, significantly higher than commercial institutions for which the ratio is nearer 10%. In practice, guarantees tend to have higher transactional costs than loans because of the need for a financier in addition to the MDB. All other things being equal, borrowers in these circumstances will be inclined to borrow through a single financier, rather than incur equivalent or higher costs in contingent loan instruments.

The last hurdle is lack of information and awareness of guarantees as a means of catalyzing private sources of finance. MDBs are essentially lending institutions and historically have prioritized their lending programs over their guarantee products. As a result, borrowers tend not to benefit from the full ambit of financing options that are at their disposal.

Major MDB guarantee operations

With these advantages and disadvantages in mind, it is important to understand the distinctions among the various development guarantees offered at the major MDBs or MDB groups selected for this article.

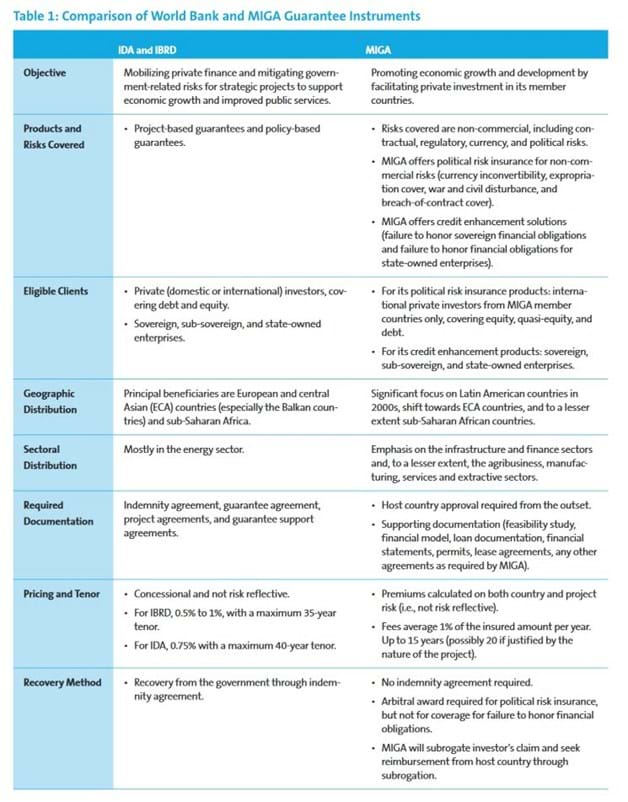

The World Bank Group, headquartered in Washington, includes the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD), the International Development Agency (IDA), the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA), the International Finance Corporation (IFC), and the International Centre for the Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID).

IBRD issues loans to governments of middle-income and creditworthy low-income countries on commercially attractive but non-concessional terms and provides both project- and policy-based guarantees. IDA issues concessional loans and grants to governments of the world’s 79 poorest countries and provides project- and policy-based guarantees.

Project-based guarantees are issued for the benefit of specific investment projects in countries seeking to attract private investment whereas policy-based guarantees support a World Bank Group member country’s policy and institutional actions through general balance-of-payments support.

MIGA provides political risk insurance or guarantees to public and private entities in order to promote foreign direct investment into developing countries against certain non-commercial risks to cross-border investments.

The IFC, the private-sector arm of the World Bank Group, issues long-term loans, equity, structured and securitized products, and advisory and risk mitigation services to private enterprises in developing and transition countries. Whereas IBRD can guarantee government obligations and seek reimbursement from the government if that guarantee is called under an indemnity agreement, the IFC is not allowed to make sovereign loans or accept sovereign guarantees as a basis for its financing. The IFC can provide guarantees against project risk and seek reimbursement from the project or the private parties if this guarantee is called, but cannot structure a guarantee with recourse against the host government.

The guarantee instruments offered by the World Bank Group can naturally converge in practice. For example, the 450-MW Azura-Edo power project in Nigeria benefited from IFC loans, MIGA political risk insurance, and World Bank partial risk guarantees or political risk guarantees to help mitigate risks. Last month, EMEAFinance magazine awarded the 2015 African public-private partnership prize to the Azura-Edo power project for its multi-sourced financing.

IBRD and IDA

The IBRD Articles of Agreement had envisaged IBRD to be a guarantee institution at the end of World War II; however, this proved to be impractical when the New York financial community became vocal about its suspicion that World Bank guarantees could “contaminate” the market for the Bank’s bonds. As a result, the World Bank Group shifted its focus to loans rather than guarantees. It was during the debt crisis of the 1980s that the World Bank decided to revisit the issue of guarantees as an alternative means of attracting more foreign direct investment into emerging markets.

By 2014, the World Bank adopted a new strategy that seeks to leverage private capital and expertise through expanded use of its risk mitigating instruments. It launched a comprehensive modernization of its guarantee policy and instrument. In brief, the reform marks a shift from defined structures (political risk guarantees and partial credit guarantees) to more flexible structures (project-based guarantees and policy-based guarantees).

The new policy also makes no distinction between countries under the non-concessional window (IBRD) and countries under the concessional window (IDA). Previously, IDA-only countries were offered political risk guarantees, but under the new policy, IDA-only countries have access to all types of guarantees (except for countries under certain fiscal or debt distress). To date, the World Bank guarantee program has seen 63 guarantee operations, with guarantee commitments valued at US$5.1 billion, spanning 45 countries. These guarantee commitments were able to mobilize a whopping US$21.7 billion in private capital.

The new World Bank project-based guarantee covers two types of risk: loan guarantees and payment guarantees. Loan guarantees cover loan-related debt service default for public or private projects whereas payment guarantees cover default of government payment obligations unrelated to loans for private projects only. The new policy-based guarantees support a World Bank member country’s program to promote growth and reduce poverty where that country already has an adequate macroeconomic policy framework in place.

As for pricing, IBRD and IDA guarantees carry the same commitment fees and commitment charges as apply to IBRD loans and IDA credits, respectively, and, in terms of the Bank’s financial exposure on the guarantee, they are booked on the same 1:1 basis that applies to loans. Pricing includes up-front fees that may be paid by the implementing entity or the private project in the case of project-based guarantees, or directly by the government in the case of policy-based guarantees. Once the guarantee fees are fixed, they remain unchanged for the life of the guarantee. In addition, commitments on IBRD and IDA guarantees count only as 25% of the country’s allocation envelope.

MIGA

Since its inception in 1988, MIGA has issued more than US$33 billion worth of guarantee commitments in more than 750 projects across the world. In 2015 alone, MIGA issued a total of US$2.8 billion in guarantees for 40 projects in MIGA’s member countries.

MIGA was established to encourage the flow of foreign investment to developing countries by providing political risk insurance, which is conceptually similar to a political risk guarantee, to cover an investor’s equity or debt exposure, or both, in a qualifying investment. Over time, MIGA’s activities became more focused on equity investments than debt obligations.

The holder of a contract can insure a government’s commitments through a MIGA political risk insurance policy covering one or more of the following non-commercial risks: currency inconvertibility, political violence and expropriation risks, breach of contract (arbitration award defaults and denials of justice) and the failure to honor financial obligations.

MIGA provides coverage for up to 15 years and, in some cases, 20 years if justified by the nature of the project.

For equity investments, MIGA can guarantee up to 90% of the investment. For loans and loan guarantees, MIGA generally offers coverage of up to 95% of the principal (or higher depending on the project).

MIGA coverage is made available to investors only if the financial payment obligation is unconditional and not subject to any defenses for non-payment from the sovereign, sub-sovereign or state-owned entity.

Just as the World Bank did, MIGA fine-tuned its insurance products in response to market demands. MIGA’s coverage for failure to honor financial obligations is the latest, non-traditional MIGA insurance product that is Basel II compliant and designed primarily to provide capital relief to commercial lenders lending to public-sector entities in a MIGA member country. Such coverage protects the guarantee holder against losses resulting from a failure of a sovereign, sub-sovereign government or qualified state-owned enterprise with satisfactory credit ratings to make a payment when due under an unconditional financial obligation or guarantee related to an eligible investment and not subject to any defenses.

In contrast to MIGA’s breach-of-contract coverage, the coverage for failure to honor financial obligations does not require the investor to obtain an arbitral award in order to file a claim for compensation with MIGA. Rather, a mere certificate is sufficient to file a claim for compensation. Among other benefits of the coverage is the timeliness of the claims determination period and the certainty of the date of payment of the claim.

With regard to pricing, MIGA prices its guarantee premiums on the basis of country, sector and transaction risks. Fees amount to approximately 1% of the insured amount per year, but can vary significantly.

Fees apply to the three different phases of the underwriting process. First, the definitive application fee amounts to US$5,000 for cover of less than US$25 million and US$10,000 for larger amounts. Second, a processing fee may be incurred where the project is complex and requires additional due diligence steps (for example, arranging a site visit). Last but not least, a syndication fee applies when MIGA secures a project’s total insurance requirements through reinsurance.

IFC

The IFC adopted an official policy on guarantee instruments in 1988, six years after issuing its first guarantee in 1982.

The IFC only issues flexible partial credit guarantees that cover non-compliance with a financial obligation (loans or bonds) up to a predetermined amount, irrespective of the cause of default. The guarantee holder is not required to obtain a sovereign counter-guarantee in order to be eligible for coverage.

In practice, IFC guarantees range from 25% to 50% of the amount of a bond issue rather than a full “wall-to-wall” guarantee.

The partial coverage guarantee avoids moral hazard risks and encourages the market to make its own appraisal of the issuer and mobilize additional funds in local markets and in local currencies, without relying exclusively on the international capital markets.

With respect to pricing, guarantee fees are consistent with IFC’s loan pricing policies. As of end of FY2015, US$3.168 billion in guarantees were outstanding (US$3.679 billion as of end of FY2014).

IADB

The Inter-American Development Bank was established in 1959 and is headquartered in Washington. It has 26 member countries located in Latin America and the Caribbean.

The IADB launched its policy on guarantees consisting of political risk guarantee and partial credit guarantees to both sovereign and non-sovereign borrowers. Sovereign borrowers are obligated to provide a sovereign counter-guarantee whereas non-sovereign borrowers are not required to do so.

The IADB’s guarantee program was originally geared toward the private sector and that continues to be the case today. No guarantees with sovereign counter-guarantees were approved by the IADB in 2013 or 2014. By contrast, non-trade related guarantees are used minimally. In 2015, only two non-trade related guarantees without sovereign counter-guarantees were approved for US$112 million (four for US$33 million in 2013 and five for US$146 million in 2014).

IADB political risk guarantees offer political risk coverage for debt instruments for breach of contract, currency convertibility, and transferability, among other risks.

IADB partial credit guarantees can extend up to 50% of project costs with a cap of US$150 million. By contrast, IADB partial credit guarantees cannot exceed 25% of total project costs with a cap of US$200 million. As for smaller economies with limited capital market access, the IADB can guarantee up to 40% of projects or US$200 million, whichever is less.

ADB

The Asian Development Bank is headquartered in Manila and is owned and financed by 67 member countries. The ADB’s financing instruments include loans, guarantees, and other risk mitigation instruments.

The ADB only issues guarantees to public and private entities out of its non-concessional Ordinary Capital Resources window, but it has discretion to direct guarantees to its lower-income concessional Asian Development Fund window.

The ADB offers political risk guarantee and partial credit guarantee instruments. While the political risk guarantee instrument is similar in scope to MIGA political risk insurance, the partial credit guarantee covers sovereign payment risks through its guarantee covering failure of a sovereign to honor financial obligations. ADB partial credit guarantees are predominantly applied in the financial services, capital markets and infrastructure (for example, power, transportation, water supply, waste treatment, telecommunications) sectors.

Unlike the World Bank Group and African Development Bank guarantees, ADB guarantees can cover up to 100% of principal and interest in special cases; however, this is not done in practice due to moral hazard risks.

The volume of guarantees approved by the ADB jumped from US$20 million in 2014 to US$341 million in 2015. However, the dollar exposure on guarantees was down in 2015 compared to 2014. As of December 31, 2015, US$809 million in non-trade related partial credit guarantees and US$73 million in political risk guarantees were outstanding compared to US$903 million in non-trade related partial credit guarantees and US$114 million political risk guarantees as of December 31, 2014.

As for pricing, the ADB uses a similar price structure as the African Development Bank for guarantees. ADB political risk guarantees require a front-end fee, a guarantee fee, and a standby fee. By contrast, ADB partial credit guarantees require a front-end fee, a guarantee fee, and a commitment fee. Policy-based pricing applies for guarantees that benefit from a sovereign counter-indemnity.

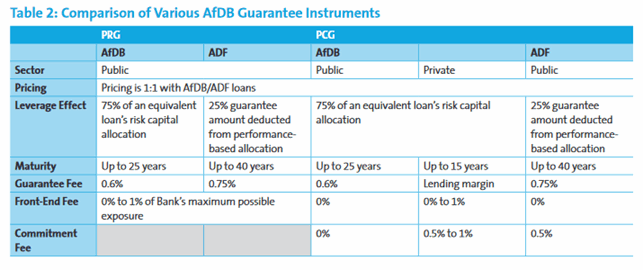

AfDB

The African Development Bank Group is headquartered in Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire. The AfDB Group’s regional member countries benefit from funding from the following three windows: the AfDB, the African Development Fund (ADF), and the Nigeria Trust Fund (NTF).

The AfDB window is used for non-concessional loans to creditworthy members while the ADF window is used for long-term low-interest loans and grants to the least developed members. The NTF window is used for financing at below-market rates for the poorer regional members.

As with other MDBs, the AfDB Group’s financial products have evolved over time, mostly in response to market demands. In addition to loans, the AfDB also issues guarantees and other risk management products. A formal guarantee policy was launched in 2004, and a political risk guarantee was subsequently issued in 2012.

The AfDB Group issues two categories of guarantees: political risk guarantees and partial credit guarantees. The AfDB guarantees share many similarities with World Bank guarantees, including the requirement of an indemnity agreement between the regional member country and the AfDB. Moreover, ADF political risk guarantees count only as 25% of the country’s performance-based allocation, which is the equivalent of the World Bank’s country allocation envelope described earlier. By contrast, AfDB political risk guarantees count toward only 75% of book value for purposes of capital risk allocation.

Table 2 shows the principal differences among the AfDB’s public and private political risk guarantees and partial credit guarantees.

The AfDB has issued very few guarantees over the past few years. In 2014, the AfDB approved only five guarantees with an approved value of US$250.7 million in total. In 2015, the total number of approved guarantees increased to seven, with a cumulative value of approximately US$965.7 million. Although the AfDB’s guarantee usage has been minimal, the Bank’s ADF political risk guarantee was used in the Lake Turkana wind power project in Kenya, Africa’s biggest wind power project, which went on to win the 2015 African deal-of-the-year award.

Trends, recap and recommendation

Table 3 shows the volume of non-trade guarantee commitments by the MDBs or MDB groups that are the focus of this article. The data spans the period 2004 through 2015 during which US$40.17 billion in non-trade guarantees were issued across the MDBs or MDB groups. It represents a mere 4.4% of total development lending by the MDBs over the same period.

As can be seen from the data, MIGA has issued the most guarantees compared to other MDBs, which is hardly surprising, given that MIGA’s mandate is tied to the issuance of guarantees. It is also apparent from the data that the global financial crisis in 2008 saw a downturn in guarantee issuances, in light of the lack of available credit in the international markets at the time.

Going forward, MDBs need to take steps to address this apparent underutilization of guarantees. As previously mentioned, guarantees face three major practical impediments: risk capital allocation, costs, and lack of visibility.

First, in terms of risk capital allocation, there are proposals to establish set-aside funds for guarantees so that their usage is marked against the set-aside fund and not their country allocations. There are also recommendations that MDBs should consider reducing the equity capital allocation for political risk guarantees because they are less likely to be called compared to partial credit guarantees.

Second, regarding costs, guarantees are currently booked 1:1 with loans despite the fact that guarantees are unfunded at the outset. The pricing for guarantees should be reduced, and loan charges should be increased, in order to stimulate greater use of guarantees, especially in the public sector, in light of their importance in achieving important developmental objectives.

Last but not least, MDBs, potential guarantee users and beneficiaries, and the wider project finance legal and financial community should promote greater awareness of guarantees and organize training programs on the technical aspects of these guarantee instruments.

This article reviewed various guarantee instruments offered across four major MDBs, giving details of the different options that eligible clients may take into consideration or MDB groups when applying for a guarantee. As discussed, the various MDBs have been compelled to fine-tune their guarantee instruments, and broader risk mitigation products, in order to adapt to modern trends and create new opportunities to mobilize additional funds in more effective ways.

To date, guarantee usage has been minimal in contrast to other forms of MDB development financing. More robust institutional and operational incentives should be adopted by MDBs in order to promote guarantee usage as an effective means of achieving important developmental objectives in emerging markets.