California Generation: Valuable Assets or Fool’s Gold?

By Dr. Robert B. Weisenmiller, Steven C. McClary and Heather Vierbicher

One hundred fifty years after the first miners struck gold at Sutter’s Mill, companies rushed to cash in on California’s newest source of riches: power markets.

In the first half of 2001, power prices routinely landed within a range of $200 to $400 per megawatt hour. Proposals for power plants, already at record levels, surged, supported by favorable perceptions of supply and demand fundamentals. In October 2001, more than 10,000 megawatts of base load capacity awaited California Energy Commission approval or had recently been approved. Another 8,000 mws of capacity was under construction. Numerous entities claiming competence in the power area approached local governments, native American Indian tribes, and businesses with offers for co-development of power plants that would provide cost containment or be a source of revenue in exchange for exclusive development rights or payment of risk capital.

By May 2002, the heady days of California’s latest gold rush were already history. Current power prices have settled back down to a range of $20 to $40 per megawatt hour. Proposed new projects are being cancelled or delayed.

Financial markets are unlikely to provide substantial additional capital for power plant construction until power issues become less politicized, California’s utilities regain investment grade credit ratings, a consensus develops around a coherent vision of a Western wholesale power market, and there is a return to stable and predictable regulatory ground rules.

These concerns haunt both investors with operating California power projects as well as those market players who only recently arrived. None of these ingredients is present now, although some progress is visible.

Given the magnitude of California’s power debacle, it will take years to return to a stable, business-as usual-environment.

Election Year

California will hold elections for statewide offices this November, including the gubernatorial race and many legislative seats. The state must also address a staggering $24 billion budget deficit. (California’s total annual budget is $99 billion.) Closing the budget deficit for this year will require the right political mixture of creative accounting and painful spending cuts and tax hikes. The budget woes do not end there and will likely return next year. Moreover, the projected shortfall assumes that California will be able to sell $11.1 billion in bonds to cover outlays by the Department of Water Resources, or “DWR,” in 2001 to purchase power to keep the lights on. The state treasurer has struggled to align the Rubik’s cube of competing interests and political agendas to achieve such a massive bond sale. Originally projected for last fall, the bonds may go to the market this coming fall or winter.

Given the November elections, most observers expect more creative accounting gimmicks than courageous leadership to come out of Sacramento this summer. The assignment of blame for the budget crisis and the state’s electricity crisis last year will be a frequent refrain through the November elections. The patience of the California public and its politicians with energy issues appeared to have been exhausted by late 2001. However, Enron’s financial meltdown, the release of “smoking gun” energy trading memos, and the plunging confidence in power market trading companies have reignited deep outrage among the California public. These financial and ethical meltdowns have handed a well-televised platform to Governor Davis and other California Democratic leaders to attempt to shift public attention away from other issues.

Little change in California’s political leadership is expected to result from the November state elections.

Davis would like to run for president. Energy policy differences between President Bush and Governor Davis could resonate as campaign issues for the next two years through 2004. California energy policy issues could remain politicized for years as a result.

Lawsuits Abound

Since the electricity crisis erupted in California nearly two years ago, the search for a culprit — or culprits — has never ceased. California officials and regulators most frequently point fingers at the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission for inaction and at independent generators and electricity traders for manipulative behavior.

California has challenged FERC on numerous fronts. Lawmakers in California eliminated the independence of the governing board of the state’s independent system operator, or “ISO,” in a direct challenge to FERC policy on transmission operators. That policy calls for these entities to operate independently of any influence by state government and other “stakeholders.” (The ISO’s board of directors now serves at the pleasure of Governor Davis.)

California regulators and lawmakers are pursuing substantial refund claims through an aggressive political strategy. A year ago, the state demanded an $8.9 billion refund from electricity generators and power marketers. Governor Davis recently indicated state officials may ask for an even larger refund in light of “new evidence” of market manipulation, and some California officials have clamored for as much as $30 billion.

The state also has asked FERC to reopen for negotiation long-term power contracts executed last year during the power crisis, challenged FERC’s policies on RTOs and standardized market redesign, and enacted legislation that challenges FERC’s jurisdiction over exempt wholesale generators and the wholesale market.

Independent generators have not escaped the state’s blame game. The state attorney general, a state Senate committee chaired by Senator Dunn, and the California Public Utilities Commission are all conducting multiple investigations to find support for lawsuits against generators.

For example, the attorney general has filed one lawsuit that challenges a number of short-term power transactions on grounds that power marketers violated federal law (section 205(c) of the Federal Power Act) by not filing rates in advance. In a separate lawsuit, the attorney general is seeking up to $2 billion from four companies for allegedly violating California’s unfair business practices law by selling power at rates above levels FERC had previously established as reasonable. A third lawsuit alleges various power marketers “gamed” California’s wholesale market. A number of class action suits have also been filed, including one by the city and county of San Francisco.

The unfortunate consequence of all the finger pointing is twofold. First, the investment climate may suffer a long-term loss of confidence and trust. Second, any efforts to move beyond the crisis are viewed as partisan maneuvering rather than valid policy positions.

A Muddled Future

While Governor Davis, the state attorney general, the legislature, and the CPUC are unanimous in their belief that California’s energy woes are the result of market gaming by power generators and trading companies and inaction by FERC, these same parties (and others) are far from agreement on how to move beyond the electricity crisis and prevent another one from happening.

One vision for California’s future electricity market is a greater role for public power, possibly by combining the newly established California Power Authority with local municipalization efforts. The California Power Authority was established in April 2001 with the passage of Senate Bill 6X as a sort of insurance policy against future crises. When the power authority began operations in August 2001, the state treasurer, Phil Angelides, characterized public power as “a birch rod” that should only be used when scolding no longer works, a reference to public power’s role as a constraint on market excesses. The power authority can issue up to $5 billion in revenue bonds. However, in reality this additional tranche of bonds is in the queue behind the pending sale of DWR revenue bonds and the need to finance loans to cover at least part of the state budget deficit.

The power authority is on a public quest for a mission. Initially, the agency wanted to contract for peaking capacity for the summers of 2002 and 2003. However DWR, reeling from criticism of the long-term contracts it signed in early 2001, was unwilling to put state credit behind any power contracts negotiated by the power authority. In February 2002, the power authority submitted an investment plan to the legislature that focuses on renewable energy and demand-side management, but again neither DWR nor any of the regulated utilities was interested in assuming any obligations to support the power authority’s activities.

A second vision for the future sees the CPUC resuming its historic regulatory role of overseeing vertically-integrated utilities. The regulatory agency is most aggressively pursuing this vision in the current examination of generation procurement policies for the state’s three investor-owned utilities. (The IOUs were unable to procure power in the market after their credit ratings fell below investment grade during the recent electricity crisis.) The CPUC is seeking to return the utilities to the procurement — and possibly generation — role by January 1, 2003.

The utilities have asked the CPUC to establish some form of up-front reasonableness standards or a review process to remove any disincentive for entering into long-term contracts. When California restructured its electricity industry in the late 1990s, the utilities were encouraged to divest their generating assets and were required to procure power from a state-established spot market called the Power Exchange, or “PX.” Utilities’ purchases from the PX were deemed by the CPUC to be per se reasonable, while any other power procurement potentially faced a retrospective reasonableness review by the CPUC. The CPUC will consider the utilities’ proposals for consistent reasonableness standards during the current procurement proceeding.

The CPUC has a number of difficult questions to answer during the procurement proceeding. They include the role of the new power authority in relation to California’s regulated utilities. Procurement issues require a number of difficult decisions. How much additional power does California require in the next five to 10 years? What is the mix of required power among baseload, peaking and ancillary service contracts? How much of California’s successful demand-side management activities last summer will persist over the next five to 10 years? How many of the DWR contracts will survive regulatory challenges? How much additional renewable power should California commit to buy? What is the future of direct access or local municipalization in California? What will the ISO’s redesigned markets look like? What is the optimal portfolio strategy considering risks and price?

These questions will have to be answered against a backdrop of conflict. Political, jurisdictional and personal conflicts erode much of the potential for reestablishing a stable investment environment based on clear and predictable market rules.

Fight Over DWR Contracts

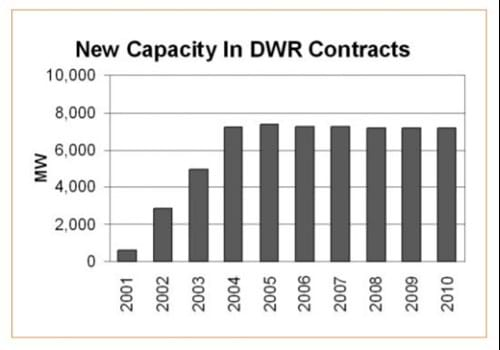

The story of how DWR became the only game in town has been recounted many times. On the positive side, the 57 long-term contracts DWR negotiated reduced credit risks for operating projects, reined in a runaway spot market, and potentially provided credit support for new projects (see chart). Governor Davis hailed the contracts on March 5, 2001, as the “bedrock of a long-term energy solution” for California.

However, DWR negotiated most of these contracts at the height of the electricity crisis when power prices were soaring. As wholesale electricity prices dropped, the DWR contracts became extremely controversial. California is now saddled with contracts that will cost an estimated $43 billion over the next ten years.

California’s state auditor performed a detailed review of the contracts and concluded that DWR had assembled a suboptimal power portfolio. The state auditor criticized the DWR portfolio for lacking sufficient peak-demand energy. In addition, many of the contracts are nondispatchable or required insufficient commitments and milestones for new construction. And the portfolio includes too many contracts where the power is delivered in southern California but cannot be sent north because of transmission bottlenecks. In the early months after signing the contracts, the agency frequently was forced to sell power at a loss during off-peak periods even while it remained obligated to purchase additional power on peak.

Concerns have also emerged that DWR may have used consultants who had conflicts of interest to negotiate the contracts. However, investigations have so far failed to turn up any evidence to corroborate these charges.

The Center for Energy Efficiency and Renewable Technologies, a nonprofit group advocating greater reliance on alternative energy, became concerned that the DWR contracts would foreclose for years to come the building of additional renewable energy projects in California. It began a broad-based campaign to force renegotiation of these contracts. The CPUC and the legislature agreed.

The CPUC is fighting the contracts before FERC. In February, the CPUC and Electricity Oversight Board filed a “section 206 complaint” at FERC against all the contracts. FERC has since decided to act as a referee for negotiations between DWR and suppliers who signed long-term contracts with the agency. In agreeing to oversee negotiations, FERC noted that neither the CPUC nor the Electricity Oversight Board has met the standard for FERC to vacate the contracts unilaterally. The negotiations began in mid-May; if they are unsuccessful, FERC will permit the adjudication of the California complaint.

California officials announced on April 22, 2002, that they have successfully renegotiated five long-term power purchase agreements entered into by DWR with Calpine, Constellation Energy, and three other developers. The restructured agreements will save the state $3.5 billion from the original $15 billion value of the contracts. As part of the deal, the CPUC voted to drop its complaint asking FERC to declare these particular contracts illegal on grounds that the companies manipulated the electricity market.

The long-term viability of the DWR contracts is based on the $11.1 billion bond issuance, which has been delayed by legal challenges and other issues. DWR is prohibited by law from contracting for electricity after December 31, 2002. DWR may continue to administer pre-existing contracts and sell electricity after that date. The new California Power Authority has volunteered to administer the contracts. Pacific Gas and Electric, Southern California Edison and San Diego Gas & Electric have said they do not want to assume the responsibility for administering these contracts.

PG&E Reorganization Plan

PG&E filed for bankruptcy in April 2001. On September 20, 2001, PG&E proposed a plan of reorganization that would enable PG&E to pay all valid creditor claims in full and to emerge from chapter 11 bankruptcy proceedings. The plan reorganizes Pacific Gas and Electric Company and PG&E Corporation into two separate, stand-alone companies that would no longer be affiliated with each other. The reorganized Pacific Gas and Electric Company would continue to own and operate the existing retail electric and gas distribution system, regulated by the CPUC. The electric generation, electric transmission and gas transmission operations will be reorganized as new businesses under PG&E Corporation and be regulated by FERC. The new entities will have the ability to issue debt. That debt, combined with new financing by Pacific Gas and Electric, $3.3 billion in cash on hand, and the restructuring of certain existing debt would be used to pay off PG&E’s creditors. The creditors would receive a total of about $13.5 billion from cash and long-term notes.

The CPUC and the state attorney general oppose PG&E’s plan. The bankruptcy court judge, Judge Montali, let the CPUC propose an alternative plan. Under the CPUC plan, PG&E would remain subject to all applicable state laws and CPUC regulation. PG&E’s shareholders would be required to contribute $3.35 billion to the creditors, including $1.6 billion of the utility’s return on equity for the years 2001, 2002 and 2003, plus $1.75 billion from the sale of additional stock. Additional cash would come from the sale of $3.9 billion of new debt and the reinstatement of $4.3 billion of long-term debt.

Creditors will be provided the opportunity to vote on these two reorganization plans starting about mid-June. Lively confirmation hearings should follow this ballot. Judge Montali has rejected PG&E’s plan for express pre-emption — a ruling that PG&E appealed — and ordered an unsuccessful mediation effort. While PG&E would like to emerge from bankruptcy by January 1, 2003, it is unlikely to do so unless there is a settlement between PG&E and the CPUC.

While PG&E filed for bankruptcy, Southern California Edison struggled along the precipice. PG&E’s filing for bankruptcy jolted the governor into negotiating a memorandum of understanding with SCE. Later, PG&E’s bankruptcy plan motivated the CPUC to negotiate a settlement with SCE that resolved the financial crisis. The CPUC’s agreement with SCE was negotiated as a settlement to pending litigation in federal court between the CPUC and SCE, and it has withstood the initial legal challenge. However, an appeal filed by an advocacy group in the US court of appeals is still pending. Despite these maneuvers, SCE is still rated below investment grade, and Standard & Poor’s has indicated that it is awaiting “concrete evidence of supportive ratemaking decisions [by the CPUC] made independently of actions mandated by the [SCE] settlement agreement.” Edison has proposed to the CPUC that it be allowed to negotiate additional long-term contracts that would rely on DWR’s credit until it returns to investment grade.

Valuable Assets or Fool’s Gold?

Just as the gold miners of years past sifted tons of dirt hoping to find nuggets of gold and most often found fool’s gold, power developers and financiers must sort through many complex issues in the California power market that potentially hide worthwhile market opportunities. There are some niche opportunities where the balance of financial risks and returns is attractive.

California’s dysfunctional power market costs Californians billions of dollars. This crisis quickly became a major public policy challenge, highlighting a dysfunctional regulatory system and forcing the bankruptcy of one of the nation’s largest utilities. The billions of dollars in dispute have sparked costly litigation and investigations. As with the original gold rush, the benefactors are often not the miners but service providers. For example, bankruptcy attorneys have had a banner year.

Even though 2002 may be an election year, it is also the year when California must begin to reassure the financial markets that the state can return to political and regulatory stability. California faces a number of financial challenges. It hopes to issue the largest municipal debt sale in US history, organize a plan that resolves PG&E’s bankruptcy, and return its major utilities to investment-grade ratings, all while addressing a massive state budget deficit. Moreover, it will need to reestablish a favorable climate for infrastructure investment. If it cannot, then it will have to choose between potential power shortages reemerging in the 2004 to 2005 period or the diversion of limited financing capability from other needs to power plants. While the worst of California’s energy crisis is past, the state has a limited period of time to construct a workable energy future.