Huge potential new demand for power

Community choice aggregators (CCAs) could displace as much as 20% to 40% of electricity load in California. They are a new kind of offtaker of renewable power.

The utilities are bracing for the loss of so many customers and charging exit fees for customers that leave the utilities for CCAs to cover their stranded costs. There is controversy surrounding the calculation of the exit fees. CCAs must take the exit fees into account when figuring out how much they can charge customers for electricity and still have an economic proposition.

This article explains how exit fees are calculated, what issues have been raised about the current methodology and proposals for reform.

What is a CCA?

A CCA is a legal entity, usually a joint powers authority, formed by one or more counties, cities or towns for the purpose of purchasing power on behalf of the residents and businesses within their boundaries. The incumbent utility, which no longer provides the electricity, still remains responsible for transmitting and distributing the power, as well as for billing, collections and other customer services. Laws enabling this structure have been passed in California, Illinois, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, Ohio and Rhode Island.

In California, CCAs are subject to the same renewable procurement targets as investor-owned utilities under the state renewable portfolio standard program. At least 50% of retail electricity sales must come from qualifying renewable sources by 2030. However, in reality, CCAs strive for even higher levels of renewables by offering customers the option to purchase electricity that has a 100% renewable energy content. The default power mix offered by IOUs is currently around 29% renewable.

The focus on renewable energy makes CCAs a significant new class of offtakers, and the power purchase agreements they sign can provide the basis for financing new projects. (For a further discussion of the financeability of PPAs with CCA offtakers, see Another Potential Offtaker: Community Choice Aggregators.)

CCAs in California

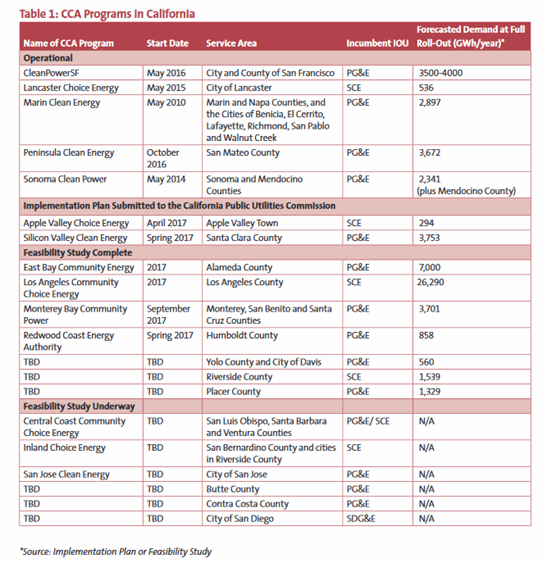

Although community choice aggregation is legislatively enabled in seven US States, California has seen the most traction. Table 1 provides an overview of operational and emerging CCA programs within the state.

There are now five operational CCA programs in California, and at least 15 more are in various stages of planning, all together covering 23 counties.

Of the planned programs, Los Angeles County and San Diego City are ones to watch. If all eligible cities participate in LA County’s program, at full enrollment it will account for approximately 40% of Southern California Edison’s total load. (SCE itself accounts for about 27% of aggregate state load.) San Diego City accounts for roughly 44% of San Diego Gas and Electric’s total load. Pacific Gas & Electric has already begun to reduce its annual procurement targets to account for existing CCAs within its service territory as well as large planned programs like the one in Alameda County. PG&E’s latest procurement plan forecasts an incremental loss of 15,444 gigawatt hours in 2017 due to CCAs, the equivalent of 21% of its 2016 load.

Exit Fees

As scores of communities in California explore the idea of forming CCAs, IOUs are facing the prospect of substantial stranded costs and the need to recoup these costs by charging departing customers large exit fees.

Exit fees are designed to cover costs of power procurement investments made by utilities on behalf of customers who later switch to CCAs or other alternative electricity suppliers. These costs would have been recoverable through electricity rates but become stranded when the customers leave. Exit fees are also referred to as non-bypassable charges because they cannot be bypassed by switching service providers.

The policy underlying exit fees has its roots in legislation passed in 2002 as part of electricity restructuring. When the electricity markets were restructured, the California Public Utilities Code was amended to provide that each retail end-use customer should bear a fair share of electricity purchase costs and obligations incurred by utilities on behalf of those customers and that there should be no shifting of costs from exiting customers to remaining customers. This policy was affirmed in S.B. 350 enacted in September 2015, which provides that bundled retail customers of an electrical corporation shall not experience any cost increase as a consequence of implementing a community choice aggregator program.

PCIA

In 2006, the California Public Utilities Commission established a special kind of exit fee known as the power charge indifference adjustment, or “PCIA,” that applies to CCA customers and customers of other non-utility energy providers under the California “direct access” program. A different non-bypassable charge applies to customers of municipal utilities. The objective of the PCIA is to ensure that the remaining utility ratepayers remain economically indifferent, meaning no better or worse off as a result of customers switching from IOUs to CCAs.

The prevailing PCIA rate charged by PG&E is between 2.072¢ and 2.363¢ per kilowatt hour for residential customers, who make up the bulk of CCA customers. (The range is due to different vintage years.) For a typical residential customer using 500 kWh of electricity per month, PCIA charges will amount to about $11 a month. Because CCAs only offer generation services, the difference between their generation rates and the utilities’ generation rates is the only basis upon which they can compete with utilities. The PCIA, which is assessed on a customer’s bill as a generation charge, therefore directly cuts into a CCA’s competitive margin. To remain competitive, the CCA must procure power at a rate that is lower than the retail rate charged by the local utility plus the PCIA.

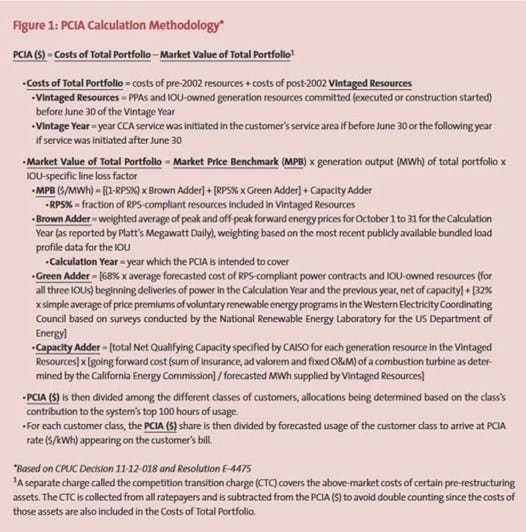

Figure 1 shows how the PCIA is calculated.

The PCIA is determined on an annual basis by comparing the actual costs of the utility’s portfolio of assets to the market value of those assets. Utilities cannot recover the entire cost of procurement, only the uneconomic portion, the idea being that they should mitigate losses by selling excess energy and capacity into the market.

The market price benchmark is a proxy for the market value of electricity. It is made up of a brown adder, green adder and capacity adder. These adders are estimates of the market value of fossil-fuel energy, RPS-compliant energy and resource adequacy (grid stability) obligations respectively.

If the total portfolio cost exceeds market cost, then the difference represents the uneconomic costs. If the costs of a portfolio are below market costs, then the difference is negative and effectively represents a credit due to the CCA customers. Negative amounts are “banked” or carried forward by the utility and used to offset the next year where there is a positive difference.

A customer is responsible only for net costs of commitments that were made before the customer departed utility service. The year the customer departed utility service is known as the customer’s vintage year. The rule is that the customer is responsible for resources committed by the utility prior to June 30 of the customer’s vintage year. Power contracts are considered committed when the contract is executed and physical resources are considered committed when construction begins.

Issues

There are three main issues with the PCIA.

First, the PCIA has a potentially unlimited duration. This follows from a 2004 CPUC decision allowing utilities to recover stranded costs associated with renewable contracts over the entire term of the contract. By contrast, the recovery period for fossil-fuel contracts is limited to 10 years.

This means that liability for PCIA fees ends only after the last renewable energy contract in a utility’s portfolio expires. PG&E has indicated that customers who switched to CCA service in 2012 and later could continue to see PCIA charges until 2043 due to three renewable contracts signed in 2010 that expire in 2043. Whether customers end up in fact paying a PCIA charge depends on whether the contract prices are above-market in any given year.

The CPUC’s 2004 decision was supposed to encourage utilities to contract for renewables on a long-term basis, thereby supporting renewable energy development. The renewables industry has since matured and CCAs have argued to the CPUC that the recovery period for all resources should be limited to 10 years.

The second issue is that the rate is volatile. As part of its 2016 energy resource recovery account application to establish 2017 rates, PG&E is proposing to increase the PCIA by 24% to 2.937¢ per kilowatt hour for customers with a 2012 vintage year. In 2016, the PCIA rate for residential customers rose by as much as 95% compared to the previous year’s rates, depending on vintage year.

PG&E has said the increases are due to reasons outside its control, such as lower market prices for both natural gas and renewables. As discussed earlier, the PCIA represents the above-market portion of generation costs, so when market prices fall, the PCIA increases.

To counteract volatility, CCAs are proposing that the market price benchmark for fossil-fuel energy be based on a five-year forward price instead of the current one-year spot price. Utilities, on the other hand, are pushing for changes to the renewable energy and capacity components of the market price benchmark, though not for reasons of volatility. They argue that the market prices yielded by the current methodology are too high, resulting in an underestimation of uneconomic costs. As shown in Figure 1, the market price benchmark for renewable assets is determined in part based on the average cost of RPS-compliant resources coming on line in the current year and the previous year. According to utilities, many contracts starting deliveries in real time were signed many years earlier when prevailing prices for renewable power were significantly higher than what they are now. They are calling for the present formula to be replaced with market indices for California RECs, such as those published by Platts.

The third issue is a lack of transparency around PCIA inputs. Without visibility into the pricing, volumes and terms of the utility contracts that underlie the annual calculation, CCAs are finding it hard to predict values and plan around potential changes to the rates.

As shown in Figure 1, the market price benchmark for renewable energy is based on the average cost of renewable resources in all three IOU portfolios that are starting deliveries in the year in question and the next year. This information is submitted by the IOUs in October each year and used by the CPUC to establish market price benchmark values for rates that take effect on January 1 of the following year.

The information is confidential under CPUC rules. CCAs can gain access through the use of arms-length “reviewing representatives,” who sign non-disclosure agreements with the IOUs limiting what they can reveal to the CCAs. CCAs are finding it hard to find consultants who qualify and are willing to act as reviewers, leaving them to resort to other methods, such as data requests and discovery, meet and confer sessions and motions to compel. The IOUs want to maintain tight confidentiality requirements because they say this information gives away their dispatch strategies, contract terms and load requirements to CCAs that are competing with them for market share. The CCAs have pointed out that they do not sell power to utilities and so cannot use price and contract information to utilities’ or bundled customers’ disadvantage. In addition to advocating for more relaxed data access rules, CCAs have also asked that IOUs provide 10-year forward forecasts of total portfolio costs and portfolio mix as these factors also influence the annual adjustment.

Reform

In its 2012 decision establishing the current PCIA methodology, the CPUC explicitly left open the possibility for reform. The commission said it would be willing to modify the calculation methodology and process based on changed circumstances in order to ensure that community choice aggregators can compete on a fair and equal basis with IOUs. Indications are that the CPUC will be receptive to proposals to reform the methodology.

In March 2016, the CPUC’s energy division held a workshop bringing together IOUs, CCAs, representatives of direct access consumers and other stakeholders to discuss PCIA reform. Proposals ranged from what can be considered granular revisions to the methodology to more fundamental, structural changes to the utility model.

One of the more fundamental proposals is to replace the annually adjusted PCIA with an up-front, fixed valuation for each vintage year. The valuation would be negotiated and agreed in a formal settlement between each CCA and the relevant IOU, and be subject to approval by the CPUC. CCAs want the flexibility to pay the fixed fee on a lump-sum basis and recover the cost from their ratepayers or amortize the payment over a period so as to cap annual increases at a fixed level.

Los Angeles County is proposing more structural changes in light of the large departure of load that would be caused by its anticipated CCA program. It argues that the appropriate way to allocate procurement costs is to transfer power contracts from the IOUs to CCAs, replace IOUs with CCAs as providers of last resort and grant CCAs reciprocal powers to charge exit fees to departing customers to recoup uneconomic generation costs. (Los Angeles County is different from the City of Los Angeles, which has its own municipal utility.) The CPUC may not have jurisdiction to require transfer of contracts, however, so this proposal may require legislative action that is not considered likely. Furthermore, the question of which contracts will be subject to assignment and whether counterparties will agree to assignment are issues that would need to be worked out.

Following the workshop, the energy division issued a report summarizing the discussions, but declined to adopt any of the proposals. Instead, it has invited stakeholders to petition the CPUC for the changes they would like made.