World Bank guarantees for private projects

The World Bank has rolled out an enhanced guarantee program, building on 25 years of experience in issuing “partial risk” and “partial credit” guarantees.

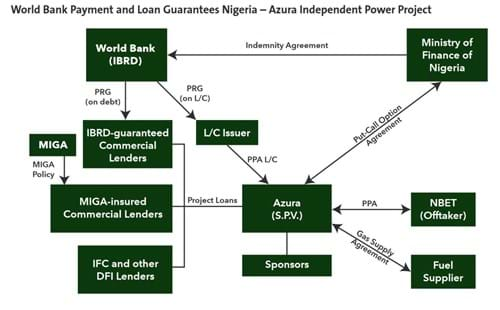

The enhanced guarantee program was recently showcased in the project financing of the 450-megawatt gas-fired Azura power project in Nigeria. This project reached financial close in December 2015 and was supported by two World Bank partial risk guarantees.

The bank’s pipeline of proposed guarantees is growing to unprecedented levels, with dozens of potential projects currently under consideration. That demand suggests that these products address real needs in the relevant markets.

This article summarizes the key features of the new forms of guarantees on offer and explores the potential impact on investment in emerging markets.

History

The World Bank was originally expected to make its primary activity guaranteeing repayment of commercial bank loans to governments in less developed countries and taking participations in such loans.

Contrary to expectations, the bank’s dominant activity since it was established in 1945 has been making direct loans to sovereigns or, subject to a sovereign guarantee, to sub-sovereigns. For a variety of reasons, guarantees have been used only sporadically. Bank guarantees traditionally have helped countries mobilize private financing by protecting private lenders against the risk of debt service default by the borrower as a result of a host government’s failure to fulfill its contractual obligations related to the project.

All World Bank guarantees require a sovereign indemnity of the bank in order to satisfy the bank’s charter obligation to take only sovereign credit risks.

The bank took a step toward issuing guarantees in 1983 by opening a B-loan program in which commercial lenders could co-finance projects with the bank by purchasing participations in certain World Bank loans. The bank suspended that program in 1988 because of concerns raised about certain risks in that structure, but that led in 1988 to the establishment of the “Expanded Co-financing Operations Program.” The revised program focused on using partial — versus all-risk — guarantees to mobilize private finance for public or joint public-private projects.

Shortly thereafter, in 1991, the bank broadened the program also to permit guarantees to support commercial financings for private sector projects. The trend at the time was toward greater private sector involvement in public infrastructure projects, and financings were being done on a limited-recourse project finance basis. The Hub power project in Pakistan was the first application of the guarantee to such a private sector project. The guarantees opened the door to a World Bank role in projects that would otherwise have had no access to traditional World Bank lending.

In 1994, the World Bank board approved the use of partial risk guarantees and partial credit guarantees.

A partial risk guarantee protects private lenders against debt service defaults on loans, normally for a private sector project, when the defaults are caused by a government’s failure to meet specific obligations under project contracts to which it is a party. Partial risk guarantees were available to both “IBRD-eligible countries,” which are the higher-income borrowing members of the World Bank, as well as to “IDA countries,” which are the lower-income members.

A partial credit guarantee protects private lenders against debt service defaults on a specified portion of a loan, normally for a public sector project, irrespective of the cause of the default. Partial credit guarantees were only available to IBRD-eligible countries.

While this World Bank guarantee program was an exciting development in theory, actual deployment of the guarantees was relatively limited for two reasons.

First, for the first decade of the program, the guarantees were offered only as a source of World Bank Group (IBRD/IDA, IFC and MIGA) support of last resort. Project developers were encouraged to seek debt from the International Finance Corporation and investment guarantees against political risk from the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency. Only if such support was unavailable, and only upon successful navigation of a host of other bureaucratic and policy barriers within and beyond the World Bank such as getting the host government to sign the required indemnity agreement, might an application for a World Bank guarantee receive serious attention.

In 2005, the World Bank decided to lower the barriers to entry into the partial risk guarantee program, recognizing that the guarantee can add value because the more conventional investment support programs through the IFC and MIGA might not address the sovereign risks of projects that depend on host government undertakings. The IFC, as a lender to private borrowers, can be deterred by the very risks of governmental breach that the partial risk guarantee program addresses. While MIGA insures against government misbehavior, it does so without a host government indemnity and without the heavy club of potentially cross-defaulting all of the host country’s outstanding World Bank loans. These two branches of the World Bank Group offer private investment support that can be complementary to the partial risk guarantee. The previous treatment of such support as substitutes rather than complements limited the availability and effectiveness of the partial risk guarantee program.

A second factor constraining host government demand for partial risk guarantees has been their accounting treatment at the World Bank. Originally, the face amount of a partial risk guarantee was fully counted against a country’s borrowing limit. In that case, if a host government were to accept a US$100 million partial risk guarantee, then it would have received no cash, only enhanced credibility permitting a privately-sponsored project to go forward. However, the ability of the host government to borrow from the Bank for public purposes, like schools and roads, was reduced by the full US$100 million. This rendered the program substantially useless for the poorest countries, which were inclined to allocate their borrowing capacity to actual borrowing rather than supporting the creditworthiness of private projects.

The World Bank in 2005 took several steps to enhance the availability of the partial risk guarantee program.

First, partial risk guarantees were no longer banned from IFC- or MIGA-supported projects.

Second, the bank around 2008 reduced the credit limit disincentives for host countries to use the partial risk product so that only 25% — versus the previous 100% — of the amount of a guarantee would count against a country’s borrowing limit.

Third, project sponsors (or lenders or host governments) were for the first time invited to approach the World Bank directly, without prior approaches to MIGA or the IFC, for an initial expression of the bank’s interest in supporting a project.

Finally, the bank announced that, going forward, guarantees could be available to support equity investors as well as lenders. This was a structural innovation rather than a formal change to the program. Equity could benefit from the partial risk guarantee through a letter of credit that is posted to guarantee performance of the host government’s obligations. If the government breach of its undertakings causes a loss, then the letter of credit can be drawn. The beneficiary of the letter of credit can be either a lender or equity investor. If the government does not reimburse the letter-of-credit bank within a certain waiting period, then the World Bank will do so, with recourse to the government pursuant to the indemnity agreement. Multiple deals were closed under this structure, including most recently the Azura power project in Nigeria.

Notwithstanding the 2005 enhancements and a record three partial risk guarantees closed that year, the bank reverted to its more usual pace in issuing partial risk guarantees over the following decade of about one partial risk guarantee a year. The bank decided that it could and should do better.

Motivation for Further Reform

More guarantee program reforms were introduced in 2013 in an effort to further enhance the guarantee to address several issues and opportunities.

More private capital is needed for public infrastructure projects. The financing needs of the developing world are large and growing. The gradual withdrawal of quantitative easing in high-income countries is leading to tighter credit conditions for developing economies. Even for developing countries that have made positive strides in market access, keeping the private financing flowing to support development is a challenge.

World Bank guarantees have not been used to their full potential. Limitations in access, policy constraints and gaps that lead to a perceived lack of clarity and added complexity by program participants have been obstacles.

Projects are increasing in size. The bank’s increasing capital constraints prevent it from participating in certain high-cost projects and programs that may be transformational and can have a significant impact on poverty reduction and shared prosperity. A more accessible and flexible guarantee policy framework helps to relieve those limitations.

More flexible and accessible guarantees allow the World Bank Group to work together more effectively to tackle client needs and catalyze private sector participation in member country projects.

The bank took a first step toward reforming the guarantee program on June 26, 2012 when it replaced its environmental and social safeguards policies with a new set of performance standards for financing of projects that are owned, constructed, or operated by the private sector. The previous dual system of the bank safeguards policies on one hand and the IFC/MIGA performance standards on the other had been a significant drag to joint World Bank Group support of public-private partnerships.

What’s New?

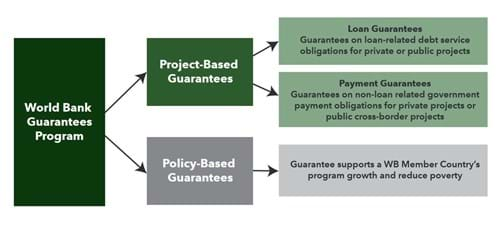

The reforms have introduced the following key updates to the prior program of partial risk guarantees and partial credit guarantees.

Under the previous policy framework, the World Bank only guaranteed commercial loans. To meet the needs of infrastructure projects where bankability is constrained by the credit risk of project counterparties, such as offtakers or, in the case of termination payments, local utilities and host governments, guarantees can now run in favor of the direct beneficiaries of a sovereign undertaking, such as the project company, rather than just being in favor of lenders.

The World Bank has traditionally offered partial risk guarantees to ensure repayment of draws on commercial bank letters of credit or by converting the host government payment obligations into a World Bank-guaranteed loan. While useful in some cases, this approach may add to the complexity and transaction costs of already complex project financings, adversely affecting client countries. Furthermore, clients are increasingly seeking World Bank guarantee coverage of non-debt-service-related government payment obligations not only in favor of private entities but also foreign public entities, where such payment obligations require credit enhancement if the project is to be bankable.

Under the prior policy framework, such guarantees could be designed in principle, but only through very complex structures that increased transaction costs and could deter their use.

The scope of bank guarantees has now been expanded to cover payment defaults in non-loan-related government payment obligations, where three things are true. The payment guarantees will help facilitate investment and serve clear development objectives under the same policy conditions that apply to bank loans. The guaranteed obligation is a direct payment obligation of a government or a state-owned entity. The guaranteed obligations would be subject to an adequate dispute resolution framework so as to avoid entangling the bank in the substance of a contractual dispute.

Such guarantees can now be issued not only in favor of private entities, but also to foreign public entities in an effort to promote cross-border, public-to-public operations.

As already alluded to, to avoid entangling the bank in the substance of any contractual dispute, bank guarantee policy requires that a project contract supported by a guarantee contain appropriate dispute resolution procedures and, if a dispute arises as to the government’s obligations, then the bank’s guarantee is triggered only after the government’s liability has been determined in accordance with those procedures. The recent reforms have clarified that this latter limitation is subject to the caveat that, in some cases, payments under a guarantee can be triggered, notwithstanding an unresolved dispute, if there is a clear government payment obligation and adequate mechanisms exist to ensure that the government is reimbursed or otherwise properly compensated should a final decision determine that the amount of the partial risk guarantee payment exceeded the government’s liability.

Also, the prior program clearly distinguished between partial risk guarantees and partial credit guarantees as separate products. The bank sees a potential for partial credit guarantees and partial risk guarantees to be used in a variety of creative hybrid guarantee structures to attract new sources of financing such as local currency loans and non-bank lenders such as sovereign and pension funds. To encourage innovative uses of World Bank guarantees, the bank no longer retains the distinction between partial credit guarantees and partial risk guarantees and intends rather to differentiate project-based guarantees by the nature of the risks that they propose to cover.

Finally, unlike partial risk guarantees, partial credit guarantees were not available to IDA countries. This restriction limited the opportunities to help IDA countries mobilize financing for critical development needs. Now, all forms of guarantees are available to IDA countries, except for those under high risk of debt distress. Considerations of fiscal sustainability are particularly important for IDA countries given their relatively limited experience with commercial sovereign borrowing and vulnerability to shocks. Thus, access to partial credit guarantees is limited to IDA countries with low or moderate risk of fiscal distress.

World Bank, MIGA and IFC Compared

The World Bank guarantees play a different and yet complementary role to the support available through MIGA and IFC, sister agencies in the World Bank Group.

MIGA provides political risk insurance of cross-border direct investments for a wide range of offshore investors and sorts of projects. MIGA could not directly match the bank’s guarantee of government payment obligations to a project company. Also, MIGA’s breach of contract coverage, patterned after similar coverage available through the Overseas Private Investment Corporation, is typically restricted to standing behind arbitral awards. If a host government is not willing to submit to arbitration in a foreign tribunal (and some constitutions prohibit doing so), then MIGA coverage may not be an option.

The IFC provides credit guarantees, in addition to its traditional project loans, for private sector projects. Neither MIGA nor the IFC requires a host government indemnity against a loss.

Like IFC financing and MIGA insurance, World Bank guarantees also support private sector projects, but only by backstopping public sector obligations for which the member country is willing to provide an indemnity.

An example of natural convergence for World Bank support is the Azura power project in Nigeria, where IFC loans, MIGA political risk insurance and World Bank guarantees were all deployed together, as depicted in the preceding diagram.

Impact on Investment

Most major infrastructure projects include the host government in one or more key roles.

The project economics may depend on the government standing behind the terms of the concession, an offtake agreement or an agreement to supply fuel or facilities. The government may have guaranteed performance or payment by offtakers or suppliers whose own credit ratings are too weak to support the financing for a project of the size proposed.

A perennial question for both project developers and lenders, when considering an emerging market infrastructure project, has been how to be able to take such host government undertakings seriously, particularly where the government in question lacks a track record of performing such obligations, either because such project structures are new to that country or its prior performance record is spotty.

The World Bank guarantee program squarely addresses such risks. In supporting the Hub power project in the 1990s, the World Bank determined that, though it could not lend to private projects, it could, with much developmental benefit, guarantee commercial loans to such a project against the specific risk that the host government might fail to perform its contractual undertakings in favor of the project or its investors.

Conventional political risk insurance coverage against expropriation conceived of insured projects as being private businesses apart from the government. In contrast, the partial risk guarantee was invented with public-private joint ventures in mind. As such, these guarantees — which have now also been offered by the Inter-American Development Bank, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, the Asian Development Bank, and the African Development Bank — fill a large gap in the fabric of effective project risk mitigation.

With its recent enhancements, the partial risk guarantee program seems to be coming into its own. In stark contrast to the generally slow rate of issuance of partial risk guarantees over the past two decades, dozens of applications are currently under review at the bank. While not all those will reach financial close, a substantial uptick in both demand for, and the supply of, World Bank guarantees in support of privately-developed infrastructure projects is evident. These numbers are consistent with the bank’s plan for the enhanced guarantees program, which is to make its guarantees more easily available to developers, lenders and host governments.

The requirement of a host government indemnity will continue, so this product will still not fit every project. It will be appropriate only for those seen by host governments as being of such priority as to merit their entering into an indemnity agreement with the bank. For those priority projects, the new guarantee program could be a powerful tool for making important things happen.

By Anthony Molle with the World Bank and Kenneth Hansen with Chadbourne, in Washington