Current Issues in Holdco Loans

Holdco loans are becoming an increasingly common strategy for financing renewable energy projects in the United States. Holdco loans are sometimes referred to as back-leveraged debt or mezzanine financing. Regardless of the nomenclature, these loans are not directly secured by the underlying project assets. They depend instead on the share of project cash flow that is distributed to the sponsor.

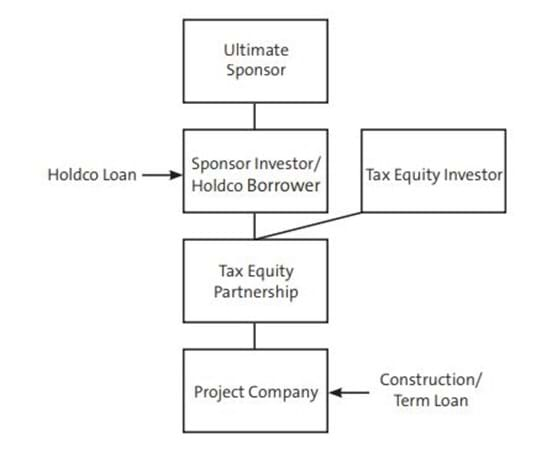

Most US renewable energy projects are financed with some combination of true equity, debt and tax equity. Holdco loans allow project sponsors to reduce the cost of capital by replacing some expensive equity in the project with cheaper debt.

Most holdco loans are entered into after construction of the project is completed.

This article focuses on a basic holdco loan structure and some issues to take into consideration when evaluating a holdco loan. It does not cover the many potential variations in structure, and readers may come across situations where holdco loans are entered into during construction or where holdco loans occupy a different space in the capital structure.

Most projects require construction financing to construct the project, and construction lenders typically rely on tax equity to repay a portion of the construction loan while the remaining construction debt converts into term debt. Because most tax equity investors are not willing to invest in leveraged projects, the portion of the construction loan that would otherwise convert into term debt, because it exceeds the tax equity available to pay down the construction debt to term, is repaid by debt that is structurally subordinate to the tax equity investor.

A simplified financing structure is shown in the figure below:

Loan Repayment

Because the holdco borrower is simply a holding company, it does not earn any revenue and must rely on distributions from its subsidiaries to pay its obligations. These distributions are often subject to claims by structurally-senior financing parties, such as a tax equity investor.

Virtually all funds that eventually are distributed to the holdco borrower originate as revenue from sales of electricity and renewable energy credits at the project company level. Funds remaining after paying operating costs are distributed to the tax equity partnership for distribution to the tax equity investor and the holdco borrower. The funds that flow to the holdco borrower will be the only funds available to repay the holdco loan.

The structural subordination of the holdco loan puts pressure on sizing the debt to take into account project performance and potential project underperformance. In addition, project-level cash flows are subject to cash traps, cash sweeps or other reallocations of distributable cash in favor of the tax equity investor in connection with indemnity claims or project underperformance. Such mechanisms prevent cash from being distributed to the holdco borrower and constrain the holdco borrower’s ability to pay debt service.

Holdco lenders will usually size holdco debt based on a scheduled amortization profile, but will often also have a target amortization profile and will sweep cash distributed to the holdco borrower for debt service in order to remain within the targeted amortization schedule. More aggressive lenders may forego such sweeps, giving the borrower more latitude on debt service, and their pricing will reflect the additional risk being taken by such lenders.

In situations where cash could potentially be trapped, swept or otherwise diverted before it reaches the holdco borrower, holdco lenders try to negotiate provisions that lead to greater cash-flow certainty. These could take the form of a limited distribution to the holdco borrower when needed to service debt, but such distributions are hard to sell to tax equity investors. In tax equity transactions in which the tax equity has the benefit of a sponsor guaranty backing certain obligations of the holdco borrower in its capacity as a partner in the tax equity partnership, holdco lenders will usually require sponsors to perform under such guarantees to prevent cash sweeps: for example, by contributing more equity to the project company to address issues that, if left unremedied, would lead to cash sweeps. In other cases, holdco lenders require that the sponsors provide acceptable credit support, often in the form of guarantees or reserves, that can be called upon if cash is swept before reaching the holdco borrower, introducing an element of limited recourse in what is otherwise a non-recourse transaction.

Change of Control

Change of control is another issue in holdco loan discussions. Holdco lenders typically receive a pledge of the equity in the holdco borrower. The holdco lenders may also receive a pledge of bank accounts, the interest that the holdco borrower holds directly in a tax equity partnership and any other assets. Most lenders focus on the equity pledge. A foreclosure on the collateral could constitute a change of control.

Most tax equity partnerships restrict changes of control in partners in the partnership. Holdco lenders must determine whether these provisions could prevent the holdco lenders from foreclosing on their collateral after a default. Even if the change-of-control provisions do not prevent the closing of the holdco loan, they could effectively prevent the holdco lenders from exercising their remedies under the holdco loan.

Holdco lenders will try to negotiate some flexibility around change-of-control restrictions with tax equity investors. These negotiations are sensitive and whatever agreement is reached is usually reflected in a separate consent between the holdco lender and the tax equity investor as opposed to being contained in the tax equity documents. The primary sticking points in these negotiations center around the ability to transfer the equity interests to third parties in connection with a foreclosure. This is separate from, and should not be confused with, the forbearance agreement that is common in tax equity deals where there is debt at the project company level. The senior lenders in such cases usually agree to forbear from foreclosing on the project or pushing out the tax equity investors for a period of time to allow the tax equity investors to reach a target yield.

It is also important to review the project documents, especially the power purchase agreement, for change-of-control provisions that could be implicated in connection with an exercise of remedies by the holdco lender.

Control Over Subsidiaries

Finally, two closely-related issues with holdco loans are the amount of control that the holdco lenders have over the project and the level of holdco lender consent required for certain actions by holdco borrower’s subsidiaries (like the project company).

Construction and term lenders at the project company level have significant consent rights and limits on the unfettered ability of the project company to act. In contrast, holdco lenders have limited consent rights and there are fewer restrictions on the project company and tax equity partnership actions. Sponsors focus on limiting the holdco lenders’ ability to block decisions that have been made or agreed to by financing parties who are structurally senior to the holdco lender while the holdco lender will want to protect its investment. Some holdco lenders approach decision making as if they are lending at the project level while others are very hands off and focus only on key matters. The differences in these approaches are, not surprisingly, reflected in pricing.