South Africa: Lessons From Projects Financed To Date

By Yasser Yaqub

South Africa has gone through two rounds of procurements for renewable energy projects. Another two to three rounds are scheduled, with procurements for fossil fuel plants to take place in parallel. It is not too soon to take stock of lessons learned from the activity to date.

The renewables procurement program is being bid for in four to five phases, with the second phase of projects having achieved financial close in May and June 2013. The third phase is scheduled for later in 2013 going into 2014; preferred bidders for projects other than solar thermal were announced in November 2013 with document close in July 2014. The bid submission deadline for solar thermal projects is March 2014 with an announcement of preferred bidders in June 2014 and document close in February 2015.

Submission of bids for the fourth phase is tentatively scheduled for August 2014.

The procurements are for technologies as diverse as solar thermal, biomass, onshore wind, solar photovoltaic and small-scale hydro.

While the current procurement program focuses on renewable power, South Africa is also expected to develop fossil fuel plants, coal in particular, in order to try and meet the expected surge in demand of 50,000 megawatts by 2030.

The first two fossil fuel peaking power plants tendered on a competitive basis achieved financial close in September 2013, after considerable delay, clearing the way for additional independent fossil-fuel power projects.

Several issues have come up in the procurements to date that are specific to the jurisdiction. This article focuses on two such issues: first, the extensive economic development obligations that are placed on developers by the tendering authority, and second, changes in the financing security structure necessitated by South African law. Both points are likely to be relevant not just for power projects, but also for other infrastructure projects in South Africa in sectors such as transportation, hospitality and mining.

Local content and economic development obligations are not peculiar to South Africa, but the scope and extent of the obligations in South Africa are greater than in most other jurisdictions in the wider region. The obligations broadly fall into three categories: ownership, job creation and local content.

Ownership

Any developer setting up a project company must ensure specific levels of shareholding and voting rights for black people and local communities. For the renewables procurement program, these levels have been set at 30% shareholding and voting rights for black people with 5% shareholding and voting rights for local communities. A similar percentage applies to the “economic interest” to be held by black people and local communities. This has probably been put in place to protect against any subversion of the obligations where parties may implement the required shareholding and voting rights but contractually or otherwise siphon off the whole or a portion of the economic benefit attached to the shareholding.

For black people, shareholding is typically organized through the participation of what are referred to as black economic empowerment or broad-based black economic empowerment — BEE and BEEE for short — corporate entities in which the shareholding is held by persons of black, Indian or other colored racial make up. To qualify for BEE or BBBEE accreditation, requirements relating to ownership, management, employment equity, skills development, preferential procurement, enterprise development and corporate social investment must be fulfilled to minimum specified levels.

While BEE or BBBEE accreditation is not obligatory, only BEE and BBBEE accredited entities are entitled to do business with the South African government or state-owned entities.

The term “local communities” refers in the renewables procurement program to towns and villages located within 50 kilometers of the project site or the closest such settlements regardless of distance if there is none within 50 kilometers. A trust is usually set up for the benefit of the local communities, and it is the trustees who then participate in the shareholding of the project company and distribute dividends and administer other funds.

Apart from the logistics of organizing BEE and BBBEE entities and setting up local community trusts, the main issue with the involvement of such entities is one of money: they usually do not have the funds to make any capital contributions to the project company.

This issue has been addressed in a number of ways, a couple of which are the project sponsors provide the funds to the black and local community entities, and the funds are then paid back to the sponsors through dividends earned once the project starts generating revenue, or a development financial institution steps in and either guarantees any financing obtained by the entities or provides the financing required directly to such entities.

Under the first approach, the sponsors are spared having to introduce an additional layer of financing. However, in doing so, they assume a greater part of the risk by having to put in all the equity.

Under the second approach, the involvement of a development financial institution has time and cost implications with a whole layer of financing and security structure having to be negotiated and put in place subordinate to the senior debt. In the South African market, where projects are not necessarily friendly to foreign lending and local banks have firm notions as to the precedent to be followed in the financing documentation, the decision to opt for mezzanine-level financing should not be undertaken lightly.

The ownership obligations do not end at the project company. The renewables procurement program, for instance, specifies shareholding and voting rights requirements of 20% of the engineering, procurement and construction contractor as well as the operations and maintenance contractor.

In instances where foreign contractors are involved, it then becomes mandatory for them to set up a South African entity with the appropriate shareholding levels in order to be able to work on the project. This has tax implications that will add to the drag on the contractor’s return.

For management control, under the renewables procurement program, 40% of the “top management” of the project company must be black people. Members of the top management are those who have responsibility for the overall management and for the financial management of the project company and who are actively involved in developing and implementing the overall strategy of the project company.

Depending on the sector, it can be challenging to fulfill the management control obligations given the dearth of qualified and suitably experienced black personnel. However, the pool of candidates eligible for top management roles is expected to rise rapidly in the coming years.

Job Creation

Job creation obligations, while steep, are not exceptional in terms of their scope.

For instance, under the renewables procurement program, 80% of employees must be South Africans of whom 50% must be black. There is an emphasis on the use of skilled labor with 30% of all skilled persons employed for a project required to be black. Local communities must also contribute 20% of the work force. (This falls within the 80% requirement pertaining to employees having to be South Africans.)

Such job creation obligations are generally a positive force in the development of South Africa where black unemployment levels are still high at approximately 30%. In addition to simple job creation, developers must also pay attention to the levels of compensation and work-place conditions offered to black people as these have been a prominent source of friction with employers as in the case of the 2012 riots at South African platinum mines that led to dozens of casualties.

Local Content

Requirements as to local content and preferential procurement are fairly common in numerous jurisdictions in the wider region of Africa and the Middle East. The obligation to spend on local content is set as a percentage of the project costs, which in the case of the renewables procurement program is 18% of the construction costs of the project. Local content covers costs attributed as having been spent on South Africans or South African products, excluding finance charges, land fees, mobilization fees of the operations contractor and any imported goods and services.

In addition to local content, the project company must also give preference to suppliers with “BBBEE” recognition levels. In the renewables procurement program, at least 60% of the “total amount of procurement spend” must be with vendors who fall within one of the eight BBBEE recognition levels. The levels reflect different degrees of black economic empowerment compliance.

The “total amount of procurement spend” is the amount spent by the project company or its contractors on goods and services in undertaking the project, excluding imported goods and services, taxation, salaries and wages.

For a project using foreign vendors for high-value portions of the project such as wind turbines or solar panels, the vendors would then have to ensure that they manage to fall within at least one of the BBBEE recognition levels to enable compliance with the preferential procurement obligation.

Levels of Compliance

It is important to note that all the percentage figures quoted are merely recommended figures set out in the request for proposals for the renewables procurement program. Developers can propose their levels of compliance and will be evaluated accordingly.

Under the renewables procurement program, developers are also required to demonstrate the level at which they will contribute to enterprise development and socio-economic development, each expressed as a percentage of the revenue of the project. The project company and sponsors also have significant reporting obligations. The project company must ensure that it has a monitoring and compliance system in place in order to fulfill its many economic development obligations.

There are significant penalties for failing to reach the required levels of economic development.

The levels of economic development to be obtained are set out contractually within the implementation agreement. Non-compliance results in the accumulation of “termination points.” The accumulation of nine termination points in any consecutive 12-month period will allow the government counterparty (in this case the Department of Energy) to terminate the concession.

Termination is not always an ideal recourse for the government, especially since the primary objective of the public sector in projects such as the IPP procurement program is to harness the resources of the private sector for the creation of much-needed infrastructure. Many parts of South Africa still suffer from brown-outs during periods of peak demand.

A less severe and permanent recourse available under the current documentation is the system of deductions and credits based on an evaluation of compliance with the economic development obligations each contract quarter. The credits or deductions are based on specific formulas that take into account deviations from the contracted levels of development obligations. A reconciliation of all credits and deductions takes place at the end of the construction period and thereafter at the end of each contract year.

The economic development obligations emanate from the need to redress the significant socio-economic disparity among South Africa’s racial groups. However, the requirements can present significant challenges. They require careful consideration and planning.

Security Structure

A typical financing structure involves a security component that complements the financing documentation and provides support to the lenders should the project run into difficulty before the project company has paid off the debt.

While many of the project financings undertaken in Africa and the Middle East involve the use of English law as the governing law of the financing documentation, the security documentation is often governed by local law due to reasons of ease of enforcement or local law requirements over security granted by the project company as a local entity.

Notwithstanding scenarios where local law governs the whole or part of the security documentation, the project company is ordinarily able to establish a security structure involving the appointment of a person or entity as security trustee to hold in trust the various securities for the benefit of the lenders that is in line with what is practiced in English law project financings.

Security documentation for South African infrastructure projects is governed by South African law. This has been the case for each of the first two rounds of the IPP procurement program. There are a few exceptions where some of the security documentation has been governed by English law such as in relation to security over reinsurance proceeds or rights under contracts (such as construction contracts) that are not governed by South African law.

Having the security documentation governed by South African law can present issues to lenders who are used to dealing with the English law structure of security documentation. For instance, it is not clear under South African law whether a security trustee may hold security on behalf of more than one lender. There also does not appear to be any legislation that would govern the role of the security trustee within the context of a financing. Accordingly, the most common practice in South Africa in relation to power and infrastructure projects has been the creation of a special purpose vehicle (commonly referred to as the “debt guarantor” in the project documentation) for the handling of the security to be created.

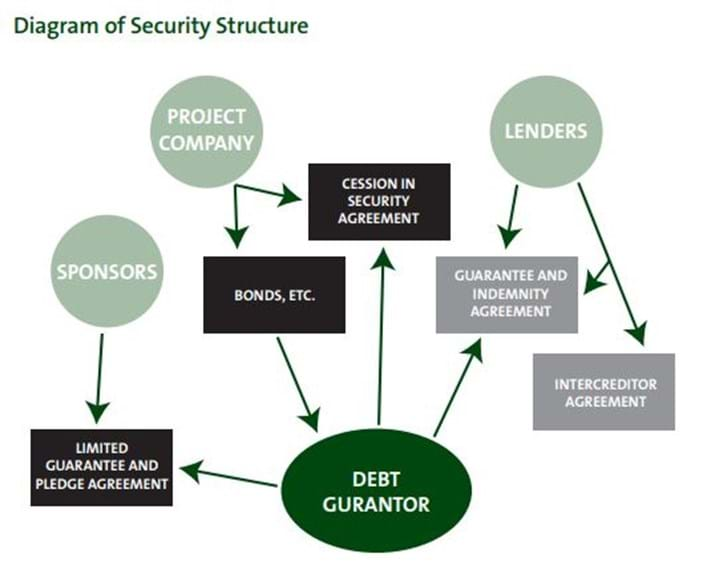

The diagram shows the contractual structures that the debt guarantor enters into with the various stakeholders in the project.

The debt guarantor is typically constituted as a proprietary limited company, which is a private company. Directors of the company are responsible for the management of the debt guarantor and are appointed with the approval of the lenders.

In order to ensure the integrity of the security that will be held by the debt guarantor, the debt guarantor is set up as a ring-fenced entity, and the only assets it holds are those related to the project for which it has been set up.

The actions of the directors of the debt guarantor are governed by the debt guarantor’s constitutional documents as well as the contractual arrangements into which it enters.

Documentation

The constitutional document of the debt guarantor is the memorandum of incorporation, which sets out the purpose, scope and powers of the debt guarantor and its directors. This document is finalized, and can only be changed, with the approval of the lenders to ensure that the debt guarantor only involves itself in business related to the project, does not jeopardize the security it holds and does not act contrary to the intent and provisions of the finance documentation.

The debt guarantor is given security over the main assets and rights of the project company and then, on a contractual basis, agrees on how it will administer the security.

The project company issues a series of bonds in favor of the debt guarantor conferring security over the project’s tangible assets (including land, plant and machinery) and also enters into a cession in security agreement that operates under South African law to cede the project company’s contractual rights under South African law-governed project documentation in favor of the debt guarantor. Any rights under English law documentation can be assigned in favor of the debt guarantor under a typical English law governed deed of assignment.

The two main documents that govern the contractual relationship between the debt guarantor and the lenders are the guarantee and indemnity agreement, or “GIA,” and the intercreditor agreement.

The GIA is used to have the debt guarantor guarantee the obligations of the project company under the finance documentation in favor of the lenders (including any hedging banks). In the event of a default by the project company, the lenders would be entitled to issue an enforcement notice to the debt guarantor requiring the debt guarantor to enforce the security it holds and make payment of realized amounts to the lenders. The intercreditor agreement operates in the normal manner in defining the relationship between, and priorities of, the various finance parties.

As a backstop to the guarantee and indemnity granted by the debt guarantor under the GIA in favor of the lenders, each sponsor is usually required to enter into limited guarantee and pledge agreement, or “LGPA,” with the debt guarantor. The sponsor guarantees the performance of the project company’s obligations under the finance documents. As security, each sponsor pledges its shares in favor of the debt guarantor. The liability of each sponsor under a LGPA is limited to the proceeds realizable from the rights attached to the shares that the sponsor holds or is otherwise entitled to, in the project company.

This form of limited recourse to the sponsors bolsters the security held by the debt guarantor, although it may not be palatable to sponsors who are not used to being subject to such recourse.

Related Concerns

Sponsors or lenders coming into the South African market will find that the finance and security documentation is to a large extent set in stone. There are a number of reasons for this.

First, the IPP procurement program has gone through the financial close of two rounds of projects and the precedents of the finance and security documentation are fairly well established. The South African finance market is a small one in terms of the number of lenders, and given the paucity of foreign lenders in the market, the South African banks have been able to establish and largely maintain a precedent that they are comfortable with and that some foreign sponsors may find too lender friendly.

While it may be possible for export credit agencies and other similar international financial institutions to get involved in lending on infrastructure projects in South Africa, the South African project finance market in general is not currently geared towards accommodating foreign lenders. For instance, it is a requirement of South African law that special permissions be obtained before security can be created over South African assets in favor of a foreign bank. Another example can be found in a clarification made by the Department of Energy during the second round of the IPP procurement program. It said termination amounts payable by the government to the project company under the project documentation exclude breakage costs payable in connection with hedging arrangements put in place to facilitate the servicing of principal and interest payments on foreign debt or to cover exchange rate fluctuations.

Given that the South African banks have so far been able to absorb the funding requirements of the IPP procurement program, there appears to be little appetite for facilitating the entry of foreign banks. This may change once we get to the third and fourth rounds of the IPP procurement program and other infrastructure projects come on line, saturating the primary and secondary finance markets in South Africa.