California: The promised land for renewable energy?

By William Monsen, Heather L. Mehta, David Howarth and Robert B. Weisenmiller

A new mantra can be heard these days in California: renewable energy is good, and more renewable energy is better.

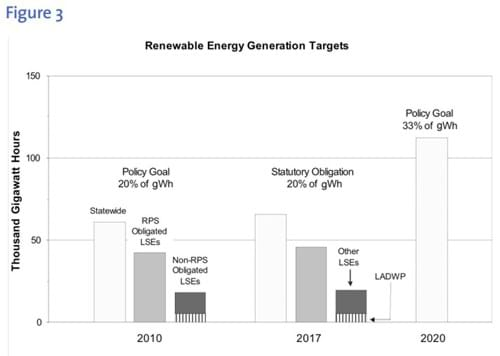

In California’s post-crisis energy market, there is nearly unanimous consensus that renewable energy should play a greater role. In 2002, the legislature passed Senate Bill 1078, which set a goal of obtaining 20% of the state’s electricity from renewable energy sources by 2017. Regulators pushed to advance the goal by seven years to 2010. More recently Governor Schwarzenegger challenged the state to raise the goal to 33% by 2020. Politicians and regulators now find themselves in an unlikely competition to be the strongest advocate for renewable energy, while both buyers and sellers of renewable energy are challenged to respond to this opportunity.

With the legislature’s passage of Senate Bill 1078, California enacted one of the most aggressive renewable portfolio standards in the nation. The statutory RPS mandate calls for certain types of electricity providers to meet 20% of their electricity load with eligible sources of renewable energy by 2017. Regulators and the state’s three major investor-owned utilities have committed to meeting that goal by 2010.

California is embarking on a path that could deliver a robust market for providers of renewable energy technologies and numerous project and financial opportunities to the investment community.

Nevertheless, California’s renewable energy goal — whether it be 20% or 33% — is a “stretch” goal for the utilities and the renewable industry. Before this promised land arrives, challenges must be met.

Progress over the past two to three years has been disappointing and is forcing some critical thinking about the regulatory framework being constructed to support California’s grand vision for renewable energy. Although there have been numerous workshops and regulatory proceedings to implement the RPS, relatively few contracts have been signed and approved. Many of those contracts are for projects that are turning out to be infeasible. Some form of mid-course correction is likely over the next couple of years. Achieving these goals will require a heady mixture of technology advances, economies of scale, high alternative fuel costs, and federal incentives. If achieved, the goals may prove to be a “tipping point” for renewable energy technologies and the industry.

Deep Roots and a Grand Future

California has long been at the forefront of promoting renewable energy technologies. Hydroelectric generation and the combustion of forest products for electricity generation date back many decades. Pacific Gas and Electric and Magma/Unocal pioneered the use of geothermal steam to produce electricity at the Geysers more than 50 years ago. In the late 1970s Governor Edmund G. (“Jerry”) Brown promoted energy efficiency, cogeneration and solar, wind and biomass technologies as alternatives to building more nuclear and coal-fired power plants. By the mid-1980s generous tax credits and standardized power sales agreements with the state’s investor-owned utilities had sparked a new phase of renewable energy development. Large-scale development of cogeneration and biomass combustion facilities, the commercialization of modern wind machines, the development of geothermal facilities using the Imperial Valley’s low-temperature and high-brine resource anomalies, and research into experimental facilities such as parabolic trough solar power plants and an integrated gasifier combined-cycle power plant all benefited from California’s support of renewable energy development.

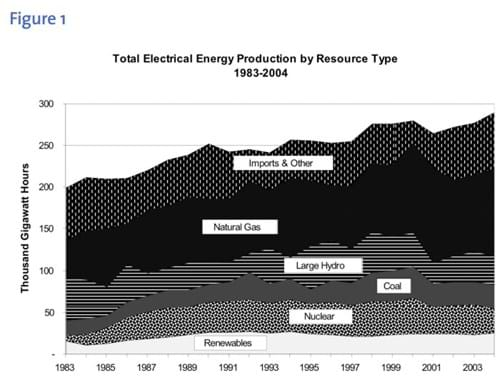

Renewable energy as a percentage of California’s overall electricity supply mix reached nearly 13% in 1993. (See Figure 1).

Readily available, low-cost natural gas, high-efficiency combined-cycle power plants and surplus power in the western US power markets eroded the competitive position of renewable energy in the 1990s.

Moreover, the public policy debate shifted focus to a reliance on market signals to lead development of new electricity supplies. As a result of these factors, renewable energy development experienced a setback in the mid-1990s. Efforts to revive renewable energy development began again in 1998 when the California Energy Commission launched its renewable energy program with funding derived in part from a public goods surcharge assessed on ratepayers’ utility bills. When the energy crisis rocked California in 2000-2001, renew- able energy generation accounted for approximately 10% of total generation, a three-percentage point drop in one decade.

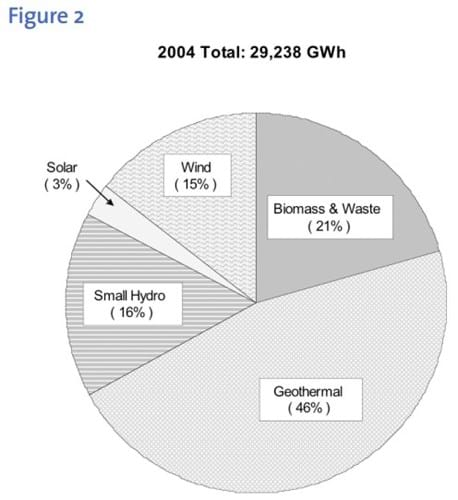

Soaring oil and gas prices, concern for climate change and lingering fears of adequate energy supply have led to renewed support for renewable energy. In 2004 California produced nearly 30,000 gigawatt hours of renewable energy. Figure 2 provides a breakdown of California’s renewable energy production in 2004 by resource type.

As one of California’s responses to the energy crisis, legislators and regulators have taken steps to increase the number of renewable energy resources that supply electricity to California. One of the most significant steps was the adoption of the 20% renewable portfolio standard in September 2002. The law requires that 20% of the energy supplied by certain retail suppliers to their electricity customers must come from renewable resources by 2017. (See the sidebar for an overview of the California RPS.) As an interim measure until the RPS legislation could be implemented, regulators ordered the investor- owned utilities to solicit contracts in 2002 for electricity generated by renewable energy resources.

Not content with the proposed pace of renewable resource development implicit in the RPS, the California Energy Commission, the California Public Utilities Commission, and the now-defunct California Power Authority authored an energy action plan in 2003 that established a more aggressive RPS target date of 2010 by which renewable energy would supply 20% of electrical load. (An updated energy action plan was released in 2005). Governor Schwarzenegger endorsed the accelerated schedule and also called for a statewide goal that 33% of the energy supplied should come from renewable energy resources by 2020. California’s RPS target is among the most aggressive targets adopted by any of the other 21 states and the District of Columbia that have adopted RPS mandates. The IOUs have publicly expressed their intention to meet the more aggressive target established in the 2003 energy action plan.

In addition to promoting the development of utility-scale renewable energy through implementation of the RPS, the California Public Utilities Commission recently authorized approximately $2.9 billion in funding for an initiative to install thousands of megawatts of roof-top photovoltaics throughout the state. This program is similar to the “million solar roofs” legislative initiative supported by Governor Schwarzenegger that stalled in the legislature. The goal of the CPUC’s program is to stimulate demand for photovoltaics through a subsidy with guaranteed funding for ten years. It replaces a smaller program administered by the California Energy Commission. The size of the new program and its regulatory stability is expected to support investment in manufacturing that may lead to a reduction in costs. Similar programs have been successful in reducing photovoltaic costs in both Japan and Germany. As the market grows and costs decline, the amount of the subsidy is reduced.

The program is expected ultimately to result in up to 3,000 megawatts of new roof-top solar capacity.

Renewable Energy Targets

The California RPS legislation established renewable energy targets for three classes of retail sellers of electricity: the investor-owned utilities, energy service providers — called “ESPs” — and community choice aggregators — or “CCAs.”

Up until the end of 2005, only California’s three major utilities — PG&E, Southern California Edison and San Diego Gas & Electric — had to comply with the state-mandated RPS target. The CPUC recently extended the RPS policies to ESPs and CCAs.

Publicly-owned utilities such as the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power are not required under the law to meet a specific renewable energy target, but they are required to develop their own RPS policies. Many publicly- owned utilities, including Sacramento Municipal Utility District and Silicon Valley Power, have aggressive renewable energy procurement policies in place. LADWP, under the new leadership of Mayor Villaraigosa, has also committed to increase its purchases of renewable energy significantly.

California’s electric loads are currently split about 70:30 between the investor-owned utilities that are regulated by the CPUC and publicly-owned utilities. Each of the IOUs’ customer bases includes bundled electric customers who procure their power from the IOUs, but also so-called direct access customers who buy their power from ESPs. In the near future, cities may begin to procure power for their residents and businesses, forming an entity known as a “community choice aggregator.” (San Francisco and Chula Vista are two cities pursuing this option.) ESPs currently provide electricity for about 13% of the IOUs’ loads; CCAs could serve another 5% by 2010.

Based on electricity demand projections made by the California Energy Commission, California’s total electricity demand in 2017 is expected to be approximately 330,000 gigawatt hours. If the 20% RPS target is achieved, renewable energy resources would be generating 66,000 gWh of electricity in 2017. Twenty percent of expected electricity demand in 2010 is 61,100 gWh, and 33% of expected electricity demand in 2020 is 112,700 gWh. Figure 3 provides a break- down of how the different targets for renewable energy translate into the need for renewable generation. (It uses the acronym “LSE” for load-serving entities.)

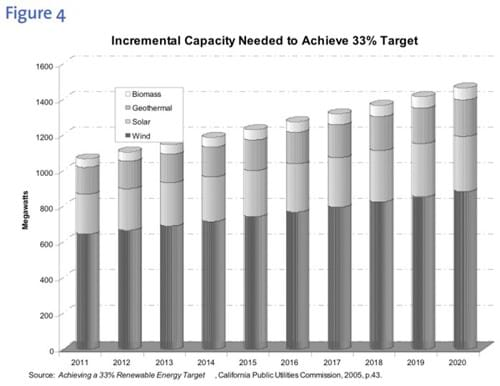

How the amount of needed renewable energy translates into the amount of new renewable generation capacity depends on which resources are developed and other factors. The key variable is the blend of the new renewable generation portfolio, since different renewable generators produce very different amounts of energy per unit of installed capacity.

Assuming that the energy targets for new renewables are met by a portfolio consisting of 50% wind, 30% geothermal, 10% biomass and 10% solar, we estimate that the state will require approximately 8,600 megawatts of additional renewable generation between now and 2010.

This would consist of about 5,200 megawatts from wind, 1,200 megawatts from geothermal, 400 megawatts from biomass and 1,800 megawatts from solar.

According to a study prepared for the California Energy Commission, a majority of this additional supply, roughly 6,000 megawatts, can be provided by resources located in California that can be delivered with little change to the existing transmission system. In order to meet the RPS target using in-state renewable resources, California will require investment in transmission capacity to enable delivery from additional resources.

Of course, the amount of new renew able generation capacity will also depend on a number of other factors, including load growth and the amount of existing renewable capacity that remains online after current contracts with the investor-owned utilities expire. Much of the IOUs’ current eligible renewable generation comes from “qualifying facility” projects, so a significant loss of these plants would result in the need for a much more rapid development of new generation, especially between 2010 and 2020, which is when most of the contracts with renewable energy QF resources expire.

To go beyond the 20% in 2010 goal to the much more aggressive target of 33% by 2020 would require a redoubling of new resource development and will require investments in transmission to access additional resources. Figure 4 presents annual capacity additions for a potential renewable development plan using the same assumptions for the new renewable portfolio as used above. As this figure shows, the state will require over 12,000 megawatts of incremental renewable capacity between 2010 and 2020 to achieve 33% renewable supply by 2020. California certainly has the technical potential to meet these targets using native resources; the California wind potential is estimated at over 15,000 megawatts with another 15,000 megawatts available from solar resources. However, given transmission constraints and other factors that limit the availability of cost-effective in-state renewable resources, the state may need to consider allowing out-of-state resources to be used to meet the 33% goal. It is important to keep in mind that the 33% target is only a policy goal at the present time and has not been fully defined. Shifting political winds, changes in fuel prices and the cost recovery associated with the state’s renewable program will all play an important role in whether the current policy goal persists over time.

Early Results

Implementation of the California RPS legislation has not proceeded smoothly, and initial timelines have been extended repeatedly to account for delays.

Regulatory proceedings to establish implementation policies have been fragmented and contentious. The CPUC has issued at least eight separate decisions over a three-year period that rule on key structural issues for implementing the RPS. Some elements of the RPS legislation are only now being considered, three years after the passage of the legislation. Moreover, unlike RPS statutes in other states, California’s

RPS legislation delegated regulatory oversight to two state agencies, the California Energy Commission and the CPUC. Utilities, project developers and other stakeholders must navigate a multi-year, dual-agency regulatory process in order to understand and comply with the California RPS.

Although the regulatory process has not been straightforward, the investor-owned utilities have completed several rounds of competitive solicitations for renewable energy since 2002. They have also negotiated bilateral contracts outside the solicitation framework. As a result of these efforts, the combined purchases of renewable energy for PG&E, Southern California Edison and SDG&E have increased from over 19,000 gWh in 2002 to just over 23,000 gWh in 2005.

Purchases of renewable energy in 2004 accounted for 13.9% of the three utilities’ combined load.

These initial results, while promising, may not be sufficient to keep the utilities on track to meet the 20% goal by 2010. In fact, PG&E under-procured renewable energy by 884 gWh relative to its procurement target in 2004 and by 1,177 gWh in 2005. Southern California Edison has also fallen short, missing its 2005 target by 274 gWh.

In addition, much of the purchases of renewable energy during the first three years of the RPS program came from existing renewable energy generation capacity. Thus, the early stages of the California RPS have not led to development of new renewable generation capacity, but rather have resulted in the diversion of sales from other buyers to the IOUs. As the annual incremental targets increase and other load-serving entities are brought in under the RPS umbrella, there will be greater dependence on new projects.

The bidding and contracting process has proven to be cumbersome as well. Early experience from the IOUs’ renew- able energy solicitations shows that it takes about two years between the time that a solicitation is held until construction on a project begins. A large portion of the delay can be attributed to utility administration of the procurement process rather than regulatory delay. For example, PG&E held a round of solicitations in July 2004 but only completed negotiations with bidders in April 2005. Southern California Edison did not complete negotiations with bidders following an August 2003 solicitation until 2005.

The California RPS legislation requires the use of a “least- cost, best-fit” criteria in the procurement of renewable energy resources. The CPUC defined “best fit” as the resources best able to meet the utility’s energy, capacity, ancillary service and local reliability needs. Because the least- cost, best-fit criteria is unique to each utility, the utilities have developed their own methodologies for how the criteria should be applied. However, the utilities provide only general, qualitative descriptions of their methodologies, creating a lack of transparency in the application of the criteria that has become quite controversial.

Contract failure is emerging as a potential major stumbling block to the achievement of California’s renew- able energy goals. Southern California Edison recently reported to the CPUC that at least six of eight projects that received contracts following its 2003 solicitation, and that were expected to be operational in 2006, may not achieve commercial operation until 2010. Additionally, a 5 megawatt solar project and a large biomass plant signed bilateral contracts with Southern California Edison, but then failed to gain regulatory approval. Given the likelihood of additional contract failures, it has been recommended that California regulators require that utili- ties contract for supplies in excess of their projected needs to ensure that the energy targets are met according to schedule and contract failure is not used as an excuse for failure to comply.

Transmission Expansion and Policies

Even if sufficient contracts for renewable energy are signed, delivering the energy and capacity from those contracted projects poses significant challenges.

Among the most critical challenges to overcome are transmission planning and permitting policies, transmission system expansion and transmission cost recovery policies. Achieving California’s renewable energy goals will require resolution of a variety of transmission bottlenecks in 2006.

The regulatory responsibility for transmission planning, permitting and ratemaking is spread across federal and state agencies and at the state level among a number of state energy agencies. In California, three state agencies have various responsibilities for transmission planning and permitting. The California Energy Commission conducts resource planning studies that identify the potential need for and size of transmission upgrades. Under its Federal Energy Regulatory Commission-approved tariffs, the California ISO has jurisdiction to approve any needed transmission projects. The CPUC has jurisdiction over the siting of transmission lines and must issue a certificate of public convenience and necessity for any California ISO-approved project that is not exempted from siting requirements. Finally, FERC must approve the inclusion of a transmission project’s costs in transmission rates. Concerns about under-investment in

California’s transmission infra- structure have led to consideration of jurisdictional reform and public disagreements between the California Energy Commission and the CPUC about the need for such reforms.

In December 2005, Southern California Edison reported to the CPUC that although its baseline renew- able energy position in 2003 was about 18%, it was unlikely to meet the 20% by 2010 goal because licensing and constructing new transmission facilities necessary to inter- connect new renewable generation projects likely would not be completed in a timely manner. According to Edison, many generation projects are located in the California ISO interconnection queue ahead of eight renewable energy projects with which Edison has signed contracts.

The typical length of time from when a generator applies to the California ISO for interconnection to the completion of the transmission upgrade ranges from approximately five to seven years.

In late January, the investor-owned utilities filed supple- mental material with the CPUC concerning the implications of transmission issues for successful implementation of their renewable plans.

Southern California Edison’s quandary may have shocked California policymakers, but they should not be surprised about the pivotal role that transmission infrastructure will play in achieving the state’s renewable goals. For example, SDG&E has frequently said in filings before regulatory authorities that significant new transmission capacity in its service area is needed to achieve the 20% renewable goal. All three IOUs may need to expand transmission capacity into areas with substantial renewable resources.

A significant amount of California’s renewable energy potential exists in areas far from the transmission system. In order for the state to achieve its aggressive renewable energy goals, at least some portion of this geographically remote potential must be tapped. However, expanding the state’s transmission system within the proposed RPS timeframe is a formidable challenge.

A number of transmission projects that would tap into California’s diverse mix of renewable resources have been proposed, including the following:

Tehachapi Transmission Plan: An area of California known as Tehachapi contains the largest wind resources in the state. Existing wind facilities have a total capacity of about 645 megawatts. The California Energy Commission estimates that the area’s undeveloped wind potential totals 4,500 megawatts (peak capacity) or 14,000 gWh per year. A group known as the Tehachapi Collaborative Study Group that includes representatives of PG&E, Edison, developers and regulators has been attempting to develop and to implement a consensus transmission plan for the Tehachapi resources. The CPUC concluded that a traditional “application-based” approach to siting transmission lines for individual projects in the Tehachapi area would not be cost-effective nor would it likely yield the level of infrastructure needed to take full advantage of Tehachapi’s wind resources. The CPUC encouraged Southern California Edison to apply to FERC for innovative rate treatment of a comprehensive approach to transmission needs for this area, but Edison received only partial approval from FERC. Consequently, Edison has applied for CPUC approval only for a first phase project known as the Antelope transmission project.

Imperial Valley Transmission Upgrade: California’s Imperial Valley contains sizable geothermal and solar resources. Existing geothermal generation capacity totals about 450 megawatts. Developers estimate there is potential to develop an additional 1,350 to 1,950 megawatts over the next 15 years. Large-scale solar thermal electric projects have also been proposed in the Imperial Valley. A group known as the Imperial Valley Study Group, comprising the Imperial Irrigation District, LADWP, SDG&E, developers and regulators is studying options for developing transmission capacity that could deliver up to 2,200 megawatts of geothermal and solar generation output to electricity customers. Plans to expand transmission access in this region have proceeded along two independent but closely linked paths.

One is the “green path project.” In November 2005, Los Angeles Mayor Villaraigosa announced that the city had entered into a partnership with the Imperial Irrigation District and the non-profit organization Citizens Energy to build the “green path” project. The project seeks to upgrade existing transmission lines and create new interconnection points that will enable LADWP to tap into the Imperial Valley’s renewable resources at the Salton Sea. The green path project would make a substantial contribution to the mayor’s goal of LADWP supplying 20% of its power from renewable energy in 2010.

The other option is the “Sunrise power link.” SDG&E recently proposed a new 500 kV transmission line, known as the Sunrise power link, to connect its service territory to the Imperial Valley. SDG&E has not determined the specific location the transmission line would travel, and the earliest projected in-service date is 2010. SDG&E contends this new transmission line is necessary in order for the utility to access much of the renewable resources that it has under contract and also to meet its RPS obligations of 20% in 2010. SDG&E has advocated use of renewable energy credits as another way for it to meet its RPS obligations, but this proposal is controversial.

Out-of-State Renewable Resources: PG&E has advocated that California evaluate its need for transmission infrastructure based upon resource availability throughout the west. Governor Schwarzenegger has led efforts by the Western Governors’ Association to plan and develop energy resources on a regional basis. PG&E is concerned that California’s efforts to find transmission solutions to access its remote renewable resources in the Tehachapi area and Imperial Valley may lead to suboptimal transmission investments relative to a plan that considers transmission solutions across the western United States. The Northwest Transmission Assessment Committee has identified large amounts of renewable resources outside California. Thus, PG&E’s ratepayers may find enhanced transmission capability to the pacific northwest more attractive than upgrades south to the Tehachapi area. In November 2005, PG&E announced a partnership with Sea Breeze Pacific West Coast Cable to study a 650-mile undersea high-voltage direct current cable that would connect the San Francisco area with the Portland area in Oregon.

The final issue that must be addressed in order to ensure needed transmission investments are made is cost recovery. Historically, federal and state policies concerning cost responsibility for transmission upgrades have laid the burden on the developer whose project causes the need for an upgrade. This first developer ends up footing the bill for a transmission upgrade that subsequent developers can utilize for their projects. This cost responsibility policy traditionally was not a problem because developers of large- scale fossil-fueled projects generally had the financial resources to absorb the costs. Developers of smaller-scale renewable energy generation projects may not have the financial wherewithal to fund a needed transmission system upgrade to accomplish project interconnection. Moreover, a series of incremental interconnection projects may have a relatively high cost relative to a comprehensive approach.

In March 2005, Southern California Edison proposed a new type of transmission line that it called a “renewable- resource trunk line.”

As proposed, the trunk line would have interconnected about 1,100 megawatts of mostly wind plants located in areas remote from major load centers. Costs of constructing the trunk line were to be recovered through general transmission rates. Although the trunk line was proposed by Edison, the line would have been operated by the state’s transmission system operator, and utilities other than Edison would be able to use the trunk line to tap renewable resources to meet their RPS goals. California’s regulators supported the proposal, but FERC did not approve the trunk line. Instead FERC provided Southern California Edison with advance cost recovery assurances for the Antelope transmission projects portion of the more comprehensive transmission plan for the Tehachapi. According to California regulators, FERC’s rejection of the proposed trunk line removes “the primary instrument the state could have used to address transmission constraints for renewables.”

The experience with Edison’s proposed renewable resource trunk line illustrates not only the challenge that cost recovery policies pose to transmission system development, but also how competing jurisdiction over transmission planning, policies and rates acts as a roadblock to achieving California’s RPS goals.

Other Implementation Issues

There are many issues that threaten to slow if not derail California’s progress toward its RPS target.

Renewable energy credits are in use elsewhere in the US, but their role in California continues to be hotly debated. Uncertainty over future extensions to federal tax incentives will continue to plague project development. Land use and other environmental quality issues may emerge during the permitting process as the number of projects seeking permits escalates. Supplies of renewable energy equipment could tighten as other states and countries step up their own efforts to develop renewable energy projects.

California does not permit unbundled, or tradable, renewable energy credits to be used by a retail seller of electricity to meet an RPS target. (A renewable energy credit, or “REC,” represents the environmental attributes of the electricity produced. An unbundled REC separates these environmental attributes from the underlying electricity, allowing the environmental attributes to be sold, or traded, separately from the electricity.) The ability to use tradable RECs to meet an RPS target could ease the pressure for transmission investments and would make meeting RPS targets easier for ESPs and CCAs. But RECs have limitations as well. Because RECs are generally traded in short-term markets, they may not provide the type of long-term financial surety that renewable energy generators historically have needed. SDG&E has sponsored controversial legislation to allow RECs to be used to comply with the RPS requirements as part of a package to move the statutory RPS date from 2017 to 2010. Governor Schwarzenegger wants to broaden the eligibility for out-of-state renewables, while consumer advocates have been concerned that REC trading would expose California ratepayers to future market abuses by REC traders akin to the electricity crisis market manipulation allegations.

An obstacle to using tradable RECs to satisfy California’s RPS targets is the current lack of a REC verification and tracking system. California’s energy agencies are collaborating with other states in the West to establish the Western Renewable Energy Generation Information System (WREGIS). The system, which is expected to be operational in 2007, would serve as an independent data clearinghouse to facilitate verification, tracking and trading of RECs.

Even if a tracking system such as WREGIS was in place, there is debate within California as to whether the RPS legislation permits trading of unbundled RECs. New legislation may be required to provide the clear statutory foundation for using unbundled RECs to meet the RPS goals.

Production and investment tax credits provide critical financial support for renewable energy technologies. In 2005, Congress approved an extension of the 1.9 cent-per- kilowatt-hour tax credit for electricity generated with wind turbines over the first ten years of a project’s operations. Without these financial incentives, the cost-effectiveness of some renewable energy projects would suffer. Congress periodically reviews these incentives and has approved extensions, but not without bruising political battles first taking place. These incentives have very specific eligibility requirements, so it will be crucial for developers to have competent tax attorneys.

A provision in the federal tax code concerning eligibility to receive the federal production tax incentive has become a major stumbling block to repowering. A repowered wind facility with a pre-1987 standard offer contract cannot receive federal tax incentives without a contract amendment. Current short-term avoided costs are much lower than many existing contract prices. Thus, wind facilities have little incentive to repower. According to the California Energy Commission, up to 1,000 megawatts of wind facilities in the state are candidates for repowering.

Most of California’s new renewable projects will be located in relatively remote locations, which may simplify land use and permitting issues compared to more urban environments. However, renewable developments in these remote locations may well have significant adverse environmental impacts, so that land use planning and environmental mitigation issues are likely to become more widespread as renewable development expands.

A related issue is the high level of bird mortality associated with the operation of wind facilities. Research suggests that bird deaths would be reduced if older, smaller wind turbines were replaced with fewer, larger wind turbines. Local officials in the Altamont area in northern California are particularly concerned with this issue and have limited the number of permits they will issue for new and repowered wind facilities.

The markets for renewable energy technologies are global and thus will be subject to the pressures of supply and demand in markets throughout the world. High oil prices have motivated many countries to push the development of renewable energy projects, resulting in a shortage of and increasing prices for certain equipment such as wind turbines. Promotional programs in certain markets may pull

critical supplies from other markets. For example, the photovoltaics market has been strong in Japan and Germany in recent years as a result of government support for this technology.

Conclusions

Implementation of the California RPS legislation has not proceeded smoothly, and initial timelines have been extended repeatedly to account for delays. Regulatory proceedings to establish implementation policies have been fragmented and contentious. The IOUs have increased purchases of renewable energy, but their solicitations have not yet generated substantial new project development

activity.

In short, the initial exuberance that led policymakers to propose the “20% by 2010” target has given way to growing concerns that procurement of renewable resources is taking too long. Patience may be the key. California has significant, untapped renewable energy resources, so while the 20% by 2010 or 33% by 2020 goals are big, they are not unachievable. Planning for the necessary transmission upgrades is ongoing, so although the timing may not be optimal, transmission lines should eventually get built. The RPS framework needs fine-tuning, but it provides a regulatory push to develop renewable energy projects. As buyers and sellers

gain experience with the RPS procurement process, they should be able to anticipate problems better and develop workable solutions. Finally, when a broad view is taken of the long-term social and environmental benefits of a greater reliance on renewable energy, California needs the RPS program to succeed.