REC market update

By James Scarrow

State programs to promote the development of renewable energy continue to multiply and evolve, presenting challenges, opportunities and some unexpected consequences for the US power market.

Background

At last count, 20 states and the District of Columbia have established renewable portfolio standards — called “RPS” — requiring electric utilities to supply a specified minimum percentage of their electricity from renewable fuels, such as wind, biomass and small-scale hydropower.

Although each state RPS program is unique, each program addresses six core issues. They are: what qualifies as a renewable fuel, the goal (frequently expressed as a percentage of the state’s total retail load), a phase-in schedule, the manner in which electricity retailers are allocated responsibility for achieving the goal, whether a utility that does not want to generate electricity from renewable fuels can satisfy its obligations by purchasing “renewable energy credits” from other, renewable generators, and the penalties for noncompliance and alternative methods for achieving compliance, such as making payments to a state’s renewable energy trust fund.

Some states have tiered RPS programs in which certain types of renewable resources are valued more than others, or in which the program has specific goals for certain types of renewable resources, such as solar energy.

The Union of Concerned Scientists estimates that RPS laws will support approximately 31,000 megawatts of new renewable power by 2017. The RPS standards in California, Texas, New York, New Jersey and Pennsylvania make them the five largest markets for new renewable energy growth. Of the 20 states with some form of RPS program, seven (plus the District of Columbia) adopted their programs since 2004. These are Delaware, Hawaii, Maryland, Montana, New York, Pennsylvania and Rhode Island. In addition to the new state RPS programs, a number of states with existing RPS programs have been ratcheting up their program goals.

On April 12, 2006, the New Jersey Board of Public Utilities approved an increase in the state’s goal for “class I” resources (which include solar, wind, sustainable biomass, landfill methane and certain fuel cells) to 22.5% by 2021, up from the previous requirement of 4% by 2008. On March 17, 2006, Wisconsin Governor Jim Doyal signed into law an increase in Wisconsin’s RPS requirement such that, by 2015, 10% of the state’s electricity will be generated from renewable sources. (The prior requirement, enacted in 1999, required that 2.2% of the state’s energy be from renewables by 2011.) In August 2005, Texas increased the goal of its RPS program from 2,880 megawatts by 2009 to 5,880 megawatts by 2015. In June 2005, Nevada raised its goal to 20% of sales by 2015, up from 15% by 2013.

Renewable Energy Credits

Renewable energy credits — called “RECs” — are a mechanism that can be used in some states to comply with the RPS requirements, and they are potentially an additional source of revenue for independent generators in such states.

Fifteen states currently use, or are intending to phase in, REC trading programs. Under these programs, a generator of renewable electricity earns one credit for each megawatt hour of electricity that is generated. RECs can then be bought, sold or accumulated and used to achieve compliance in that same year or to meet future year compliance requirements. The rules for earning and transferring RECs vary from state to state, but the building blocks of a REC program are certification and distribution of the RECs by the administering authority to generators, a tracking system and a sunset date at which time the REC expires unless used.

Through state REC programs, the renewable attributes of energy are unbundled from the electricity commodity. This has several important implications. First, because RECs are credits rather than physical commodities, the transfer of a REC from a seller to a buyer does not occur over transmission lines but rather as an accounting entry. Second, renewable electricity generators can, in theory, have two separate revenue streams — one from the sale of commodity electricity and one from the sale of RECs — allowing generators to seek the maximum sales price for each individual stream. (In practice, various states have proceedings underway to decide who owns the RECs in cases where the electricity is sold by an independent generator to a utility. Utilities argue the RECs convey with the electricity.) Third, the market forces can be harnessed to help ensure that a state’s RPS goals will be achieved in an economically-efficient manner.

In order to ensure that an individual REC is not used more than once to meet RPS compliance requirements, it is necessary to have a REC tracking system. REC tracking systems give unique identification numbers to each unit of renewable energy generated, which allows the RECs to be tracked from generator to subsequent owners until the REC is used by a utility for compliance. There are now five REC tracking systems in operation or planned. They cover 1) Texas (managed by the Electric Reliability Council of Texas, also called ERCOT), 2) 11 western states (managed by the Western Renewable Energy Generation Information System and expected to launch in 2007), 3) the states in the New England power pool, 4) the mid-western states (to be managed by the Midwest Renewable Energy Tracking System) and 5) for the states within the “PJM” region (including Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Maryland, Virginia and Delaware) (managed by the PJM Generation Attribute Tracking System).

According to a 2005 study by Ed Holt & Associates, the 2004 market for RECs was about 10 million megawatt hours. This year, that number will be closer to 15 million.

REC Prices

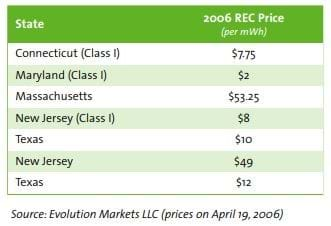

The markets for RECs vary from state to state and are driven by the specific regulatory requirements of the respective RPS programs and the laws of supply and demand. While some states have experienced relatively stable REC pricing, others have seen drastic fluctuations.

The most dramatic price swings have occurred in the Connecticut REC market. Connecticut belongs to the New England Power Pool (NEPOOL), along with Massachusetts, Maine, New Hampshire, Rhode Island and Vermont. Of these six states, four — Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts and Rhode Island — have RPS programs that allow utilities to satisfy their RPS requirements by purchasing RECs from generators anywhere within NEPOOL, including generators located in New Hampshire and Vermont, which do not have RPS programs. In 2003, the Connecticut legislature increased the state’s requirement for the use of renewable energy. Connecticut REC prices promptly spiked from $1 to $40. At the time, experts anticipated that the demand for Connecticut RECs would continue to outpace supply by as much as 50%, presumably resulting in stable or escalating prices. Instead, the opposite happened because of an oversight by such experts on how class I RECs were defined under the Connecticut RPS regulations.

Specifically, class I renewable resources were defined in the regulations to include eligible biomass facilities constructed on or after July 1, 1998; however, an eligible biomass facility constructed before July 1, 1998 can also qualify as a class I renewable resource if the facility was re-tooled to incorporate certain emission control technologies. As a consequence, when a number of re-tooled biomass facilities in Maine and elsewhere in New England came on line in 2005, the Connecticut REC market was flooded and REC prices crashed from approximately $35 to $40/mWh in June 2005 to $5 to $6/mWh in November 2005. The price of Connecticut RECs today is about $7/mWh.

In contrast to the dramatic swings in Connecticut REC prices, in neighboring Massachusetts, REC prices have continued to bump up against the RPS program’s alternative compliance payment price of $50 per megawatt — that is, the payment a utility can make into the state’s renewable energy trust fund as an alternative method of achieving RPS compliance. The consistently high price of RECs in Massachusetts may be due in part to the challenges of permitting new projects in the state, such as the proposed Cape Wind project off Cape Cod, but are primarily due to the state’s relatively narrow definition of what qualifies as “renewable energy.”

Massachusetts officials appear mindful of the depressing effect that a broadening of the definition of qualifying renewable resources could have on REC prices. Thus, in October 2005, the Massachusetts office of consumer and regulatory affairs and business regulation issued a policy statement clarifying that, in contrast to the Connecticut RPS program, re-tooled biomass facilities would be qualified to produce Massachusetts RECs only to the extent that the energy produced by the re-tooled facility represented an increase over its historic generation rate and not for each megawatt of energy produced by such re-tooled facility. By making this clarification, Massachusetts in effect supported the prices of its own RECs while adding continued downward pressure on the price of Connecticut RECs because re-tooled biomass facilities located in New England can qualify for Connecticut RECs but not Massachusetts RECs.

In Texas, REC prices have not experienced the wild swings seen in Connecticut, but they have not been as robust as many had predicted. Under the Texas RPS program, each electricity retailer in Texas is allocated a specific number of megawatt-hours of renewable energy for which it is responsible, based on the retailer’s share of the statewide electricity retail market. The allocations were originally made assuming a capacity conversion factor of 35%. (The capacity conversion factor represents the actual output from a facility relative to its maximum potential output over the same period of time. Because of the intermittent nature of wind, a capacity factor of 35% for a wind farm may be typical, whereas a gas–fired plant might have a capacity of 90%.) For example, the statewide RPS requirement of 1,400 megawatts of new renewables capacity for calendar year 2002 translated into 1,226,400 mWhs of load that were required to be supplied with qualified renewable energy for that year (i.e., 400 mws x 8,760 hours/year x 35%). REC prices in Texas have hovered in the $11 to $14 range for the past few years even though Texas significantly increased its RPS goals in 2005. In conversations with the NewsWire, people who are active in Texas renewables expressed some disappointment that prices have not risen. One reason cited for depressed Texas REC prices is ERCOT’s downward adjustment of the capacity conversion factor from the original 35% to 27.9%. The effect of this adjustment has been a 20% decrease in the megawatt hours of RECs that utilities would otherwise have to buy for any given RPS annual requirement.

REC Ownership

Where the power purchase contract is otherwise silent on the issue, disputes have arisen over whether utilities that purchase electricity through long-term contracts are entitled to the RECs associated with that electricity.

Under PURPA (the acronym for the “Public Utility Regulatory Policies Act of 1978”), utilities are required to buy power from two types of independent power plants (so-called “qualifying facilities” or “QFs”) at the “avoided cost” the utility would have to pay to generate the electricity itself. Most power purchase agreements between utilities and independent power producers were entered before enactment of state RPS programs and, therefore, do not address the question whether the power purchaser from a QF is entitled to any RECs associated with the electricity being sold.

States that have determined that RECs convey to power purchaser for existing and (where indicated) new QF contractsConnecticut (existing), Colorado (existing), Maine (existing), Minnesota (existing), North Dakota(existing and new, with compensation), New Jersey (existing), New Mexico (existing and new), Nevada (existing), Texas(existing), Wisconsin(existing).States that have determined that RECs are retained by the QF for new contractsColorado, Nevada, Oregon, Rhode Island, Texas and Utah.States with ongoing proceedingsArizona and Pennsylvania.

|

A recent study by Ed Holt & Associates identified 16 states in which QF REC ownership had been addressed by states. In each of these states, other than New Mexico, the determination of REC ownership was determined by regulation rather than legislation. In some states, the determination of REC ownership has hinged on whether the underlying power purchase agreement pre-dated a specified regulatory determination or regulation in that state. States have consistently awarded REC ownership to the utility power purchaser in the case of pre-existing contracts. However, several states have awarded RECS for new contracts to the QF even if the contract was silent on REC ownership.

Prospects for Long-Term REC Contracts

REC purchase agreements have held out the possibility of providing a second potential revenue stream for renewable energy projects. However, to date, creditworthy REC purchasers have been reluctant to enter into REC purchase agreements for terms longer than five years. As a result, the revenue streams from REC sales have generally not been able to support long-term financings, which can have 10- to 15- year terms.

One of the reasons that long-term REC purchase agreements have been rare is because of the way electricity markets have been restructured. In many restructured markets, such as the New Jersey market, electricity distribution companies bid out their basic generation services through an auction process. Through this process, the winning bidder provides generation services — including compliance with New Jersey RPS requirements — for a specified portion of the overall load and typically for a period not exceeding three years. Because the winning bidders provide those services for a relatively short period, they are unlikely to enter into long-term REC purchase agreements.

The price volatility seen in markets such as Connecticut, coupled with the regulatory uncertainty inherent in the rapidly evolving patchwork of RPS programs, has further dampened enthusiasm for long-term REC contracts.

According to Andrew Kolchins, director of environmental markets at Evolution Markets LLC, while a limited number of long-term REC contracts have been entered to date, hedge funds and other potential investors have been showing increased interest in taking speculative REC positions. Such interest may signal the next step in the maturing of REC markets.

“White Tags”: the New Certificate

Even as the REC markets experience some growing pains, states continue to push forward with new market-based innovations to encourage sustainable energy projects. So-called “white tags” are a new form of energy certificate in which each “tag” represents one mWh of energy savings measured against a specified baseline. The idea is to encourage capital expenditures on energy efficiency projects, with the resulting white tags being fungible with RECs as an alternative way to satisfy RPS requirements. White tags can be sold in a similar manner as RECs and reward those who have instituted energy efficiency improvements as demonstrated through established criteria. Three states have included white tags as part of their RPS programs — Connecticut, Nevada and Pennsylvania. In 2007, the Connecticut program will be the first one to go on line. It is expected that white tags will fetch the same price in the market as RECs, since a single white tag will “buy” the same amount of RPS compliance as a single REC.

Issues to Watch

As regional REC tracking systems establish themselves, planning is proceeding in earnest on how the various tracking systems might be harmonized to prevent double counting and create a “common currency” for renewables. The effort is being led by the North American Association of Issuing Bodies, a voluntary association of certificate tracking systems, regulators and other interested parties. Another development to keep an eye on, according to Ed Holt, president of Holt & Associates, is the way in which state and federal governments will resolve potential conflicts between the objectives of REC programs and air emission cap-and-trade programs. Specifically, how will states seek to harmonize REC tracking systems and the separate tracking systems currently in place for air certain emissions cap and trade programs? Holt notes that absent coordination between REC and emissions programs, the development of renewable energy generation may not result in their full “advertised” environmental benefits since these projects will not reduce the emission caps under clean air programs and the price of emission credits will be unaffected or even reduced by the expansion of renewable energy resources.