Ideas for cash investors in US solar projects

Private equity funds, pension funds and foreign investors have a hard time investing in US solar projects because they cannot use the tax benefits to which the owner of such a project is entitled.

Worse, their participation could cause the project to lose eligibility for most of the tax benefits.

Wealthy individuals, S corporations and closely-held C corporations also have a hard time investing in solar, but for a different reason. (A closely-held C corporation is a corporation in which five or fewer individuals own more than half the stock.) Their problem is that passive loss and at-risk rules make it hard for them to use the tax benefits.

However, there are still ways for such investors to participate.

US solar projects qualify for tax benefits worth 56¢ per dollar of capital cost. Few solar developers can use them. The benefits are a 30% investment tax credit and five-year accelerated depreciation. Most developers try to enter into complicated tax equity transactions to get value for them. A developer must have a significant amount of equity in the project before the tax equity market will be interested. This creates demand for cash investors to help put in equity.

This article discusses three financing structures that cash investors might use.

As a starting point, a cash investor must invest through a “blocker” corporation – a US entity treated as a corporation for tax purposes – if the cash investor is a government or tax-exempt entity or a partnership with any such entities as investors. This is to prevent its participation from denying the project the investment tax credit and accelerated depreciation. It must also be careful to ensure the blocker is not considered owned 50% or more by tax-exempt or government entities or the blocker will itself be treated as a tax-exempt entity.

Cash investors should understand how the tax equity works since they will be investing alongside it. It will also affect what the cash investor can get out of the deal.

Partnership Flip

Many solar tax equity transactions use a partnership flip structure where a partnership holds the solar asset, either directly or through a project company.

In a typical partnership flip, the sponsor forms the partnership with a tax equity investor. The partnership allocates 99% of the taxable income and loss to the tax equity investor until it hits a certain threshold, at which point the tax sharing ratios shift to a different ratio. The threshold can either be a fixed point in time, or a variable point at which the tax equity investor hits a target yield.

Cash can generally be distributed in any manner the parties wish, subject to one major caveat: the demands of the tax equity investor.

Tax equity will require enough cash to allow it to reach a minimum pre-tax yield. Most tax equity investors require at least 2%, treating tax credits as equivalent to cash. There will be additional cash flow requirements depending on the flip mechanics. In a yield-based flip, tax equity will need to get enough cash to allow it to reach its target internal rate of return by a specified deadline. If the flip is delayed, tax equity will want a greater share of cash until it reaches its target, up to 100%. In a time-based flip, the tax equity investor usually asks for preferred cash distributions ahead of the other partners.

Tax equity may require cash that the other partners would normally get to be diverted to it to cover indemnity payments or other obligations of the partners. A cash investor can expect to be subject to this kind of cash sweep in cases where it is affiliated with the sponsor. Otherwise, it should be able to avoid having its share of cash swept. The sweep will be an issue when the cash investor partners with the sponsor in an upper-tier partnership above the project-level partnership.

Potential demands on cash flow to cover sweeps lessen the appeal of a partnership flip from a cash equity investor’s perspective. The balance of this article discusses two alternatives to standard partnership flips. The structures are intended to maximize cash returns and minimize sweeps. The alternatives are inverted lease transactions and sale-leasebacks.

Inverted Lease

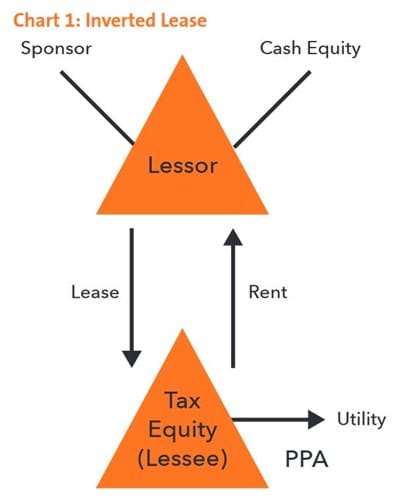

One alternative is an inverted lease. There are two types: a basic structure where the sponsor is the lessor and leases the project to a tax equity lessee, and an overlapping-ownership structure where the lessee is also a partner of the lessor. Only the basic structure would make sense as a cash equity investment.

In a basic inverted lease, the sponsor forms a lessor to own the project, and then leases the project to a tax equity investor and assigns it the associated customer agreements. The lessor makes a tax election to treat the lessee as if it had purchased the project from the lessor at its fair market value. The lessee is entitled to claim the investment tax credits. The lessee collects the revenue from the customer agreements and pays it to the lessor as rent under the lease. The lessor still owns the project for tax purposes, so it keeps the depreciation. The asset comes back to the lessor automatically at the end of the lease.

There is an investment opportunity at the lessor-level. A cash equity investor could form the lessor as a partnership with the sponsor. The sponsor would be responsible for managing the entity. The lessor could be structured either as a partnership flip or with fixed cash and tax sharing ratios. The cash investor can negotiate to get as much cash as it can out of the lessor. The sponsor can keep most of the depreciation. The sponsor could also receive an option to purchase the cash investor’s interest after it hits a target return, and get the asset back from the lessee at the end of the lease term.

The structure is shown in chart 1.

For cash investors, this structure avoids a direct partnership with tax equity and any associated cash sweeps. Like a back-leverage lender, the cash investor is investing against a share of the sponsor’s cash flow, with the added benefit that it will receive some share of depreciation. It can negotiate for as much cash as it can get without having to pay for unwanted tax benefits.

This structure is also attractive for sponsors in need of additional funds in the capital stack. Basic inverted lease transactions usually only raise a portion of a project’s cost, in part because the sponsor cannot monetize the depreciation. Other sources are needed to build the project. Sponsors often seek back-leverage loans that are repaid from the sponsor’s cash flow. The loans are typically secured by the sponsor’s equity interest in the lessor and the assets. From the sponsor’s perspective, an upfront investment by a cash investor in exchange for a share of the cash flow is functionally similar to back-leverage financing, and the sponsor avoids having to pledge its equity interest as collateral.

The structure is essentially the same as a standard inverted lease for the tax equity investor. The investor receives the investment tax credits and a step up in its tax basis for calculating the tax credits from cost to fair market value.

Sale-Leaseback

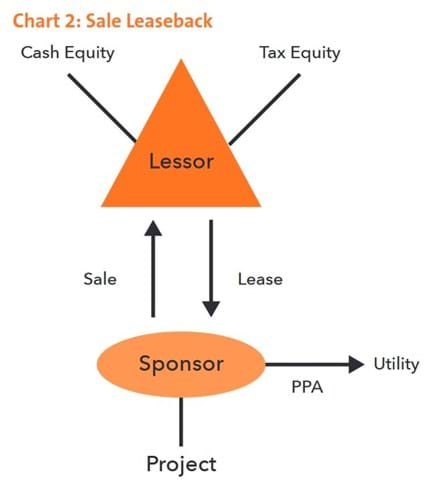

Another option is a sale-leaseback. In a typical sale-leaseback, the sponsor sells a project to a tax equity investor for its fair market value, and the investor leases it back to the sponsor. The tax equity investor keeps all of the tax benefits, and receives cash from the sponsor in the form of rent paid under the lease. The sponsor has taxable gain on the sale to the extent the value of the property exceeds what it cost to build.

The lessor position in a sale-leaseback is not usually appealing to a cash-focused investor. It might make sense, however, if the cash investor can bring in another investor with a greater appetite for the tax benefits. The cash investor could purchase the project, lease it back to the sponsor, and then sell a portion of its lessor interest to a tax equity investor before the project is placed in service. The cash investor can negotiate to keep a percentage of cash flow and depreciation as a syndication fee. The cash investor would recognize taxable gain to the extent it charges a premium on the sale of its lessor interest.

Chart 2 illustrates the structure after the cash investor has sold a portion of the lessor interest.

The main benefit of the structure from a cash investor’s perspective is flexibility. It acquires the project prior to tax equity coming on to the scene. Cash equity is in a position to negotiate to sell as much or as little of an interest in the lessor as it wants, and retain as much of an interest in the cash flow as it can get. If cash equity has some appetite for tax benefits, but not enough to justify being a full tax equity investor, then this structure allows it to retain tax ownership to the extent needed to claim the tax benefits that it can actually use. Like a standard partnership flip, however, the tax equity investor would have certain cash flow requirements that would need to be met. There would also be some time pressure to find a tax equity partner before the project is placed in service for tax purposes.

From the sponsor’s perspective, this is just like a typical sale-leaseback. Sale-leasebacks are attractive to sponsors because they offer 100% financing for a project. The sponsor bears operational risks and offtaker credit risks. A downside compared to an inverted lease is that the sponsor has to pay fair market value for the project to get it back at the end of the lease term. The investor’s initial purchase price may also not capture as much residual value as the sponsor would like.

This structure is not ideal from a tax equity investor’s perspective. Tax equity investors usually have up to three months after a project is placed in service to buy it and lease it back in order to claim an investment tax credit. The three months would not be available in this case. The tax equity investor would have to become a member of the lessor before the asset is placed in service, and would therefore have to take on some degree of construction risk. Other than the three-month rule, however, this is similar to the lessor position that tax equity would hold in a standard sale-leaseback.