Holdco loans: Trends and issues

Most renewable energy projects in the United States are financed with a combination of equity, tax equity and debt. Increasingly, the debt is holdco debt (also called back-levered debt), meaning the borrower is not the project company but rather an entity higher up in the corporate structure.

For some time, holdco debt was only term debt and the construction debt remained at the project company. However, the structures have evolved so that, in many transactions today, even construction debt is at the holdco level for simplicity of documentation and structuring.

Such debt is structurally subordinate to the tax equity financing, creating issues for lenders.

This article addresses trends and issues that have emerged recently in negotiating holdco loans.

Structures

Holdco loans can take more than one form.

When holdco loans were first starting to be used, there were usually different loan agreements at the project company level and the holdco level. A construction loan agreement and separate holdco loan agreement were sometimes signed at the same time. Funding under the holdco loan agreement was delayed until commercial operations, at which time the construction financing was paid off and the tax equity investor made its full tax equity investment. The holdco borrowing and the tax equity investment were used to repay the construction loan.

A variation on this early structure is sometimes still used. For example, if there is no tax equity commitment in place at financial close either because the construction period is too long for tax equity to commit or the sponsor has simply not been able to obtain a tax equity commitment, the construction financing will be at the project company level. Once tax equity is found, the holdco borrower enters into a new holdco loan agreement or the existing loan agreement at the project company level is assumed by the holdco borrower. A number of issues arise when deciding how to alter or move the debt from the project company to the holdco borrower. They include fees, continuity of security and how the lenders’ commitments are booked internally.

Another reason the early structure may still be used is to get around a tax problem created in situations where the sponsor has to guarantee repayment of the project debt. Under US tax law, when that sponsor enters into a partnership with a tax equity investor to own the project, the fact that the project debt is guaranteed will require an amount of depreciation on the project roughly equivalent to the debt to be allocated to the sponsor. This could also drag tax credits with it to the sponsor. It undermines the tax equity financing because there are fewer tax benefits to allocate to the tax equity investor. Moving the debt to the level of the sponsor partner after the project has been placed in service avoids the problem.

In order to streamline the documentation, most recent deals put both the construction and term debt at the holdco level. This reduces complexity because only one set of financing documents is required and there is no need to work through issues surrounding moving the debt from the project company level to the holdco level.

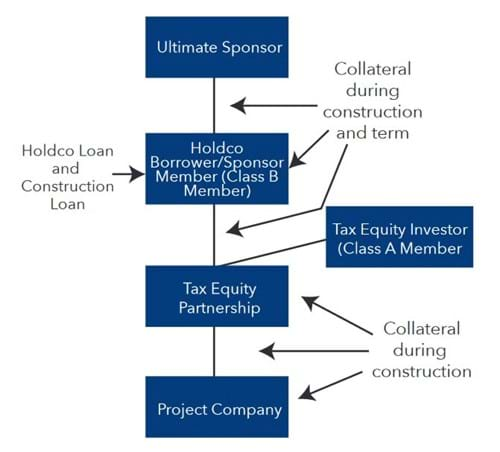

This structure still provides the lenders with typical construction loan-type collateral. During construction before the tax equity fully funds, the lenders have security in all assets of the project company, the entity that is or will become the tax equity partnership and holdco borrower and a pledge of the equity in the holdco borrower. Upon commercial operation (and repayment of the construction loan and conversion to the term loan), the collateral at the tax equity partnership and project company level is released so that the term lenders have a lien solely on the assets of the holdco borrower (meaning its interest in the tax equity partnership and all bank accounts) and the equity in the holdco borrower.

This structure is shown below.

Holdco loans emerged primarily because market terms for forbearance between project-level lenders and tax equity investors fell apart, forcing virtually all term debt to be junior to tax equity. There has been some movement in the market back toward leveraged tax equity transactions where the term debt is ahead of the tax equity in the capital stack. However, such transactions still remain rare.

Whether the debt is ahead of or behind the tax equity requires negotiation of inter-creditor issues. In cases where it is ahead of tax equity, the tax equity requires the lenders to agree to forbear from foreclosing on the project assets before the tax equity investor has had a chance to reach its target yield. The lenders can step into the sponsor role as managing member of the tax equity partnership in the meantime. In cases where the debt is behind the tax equity, then a consent will have to be negotiated governing terms for the lenders to be able to foreclose on the sponsor interest in the partnership. This is needed because the tax equity partnership agreement will restrict changes in control of the sponsor partner without tax equity consent. In some transactions, the equivalent of a consent is negotiated in the partnership agreement. Another issue is there are usually situations where the tax equity investor can sweep cash at the partnership level, leaving too little cash to pay debt service on the holdco debt.

Issues

Holdco loans raise issues that are not present with loans at the project company.

For example, if the project requires letters of credit such as the credit support required under a power purchase agreement and the LC is part of the holdco loan arrangements, then repayment of any loan resulting from a draw on the letter of credit should receive priority repayment. Sometimes the repayment will be classified as an operating and maintenance expense. The reason is that, despite technically being a financial obligation of the holdco borrower, it is in reality an operation and maintenance-type obligation of the project company and should be repaid senior to the payment of any amounts due to the tax equity investor.

Another unique feature of holdco loans is the insurance provisions. Lenders usually want to control whether and how a project is rebuilt after a casualty or whether insurance proceeds should be used instead to repay the debt. However, the tax equity may not see why a lender who is subordinate to it in the capital structure should have a say in such decisions.

The tension spills out in a number of ways. The holdco lenders will not want the tax equity investor to be named as a loss payee on the insurance policies to ensure any insurance proceeds are not paid directly to the tax equity investor. The lenders will want the project company or the tax equity partnership to be named as sole loss payee.

If the tax equity partnership agreement specifies when insurance proceeds will be used to rebuild the project, then the holdco lenders will want to be comfortable that the rebuilt project will still be able to service the debt and, if the project is not rebuilt, enough insurance proceeds will be distributed to the sponsor partner to pay off the outstanding holdco debt. The lenders will almost never find it acceptable for there to be a flat requirement to rebuild the project. Any discretion the sponsor partner has, as managing member of the partnership, whether to rebuild will need to be subject to the approval of the lenders.

Cash sweeps

Because holdco loans are structurally subordinate to the tax equity, potential cash sweeps and cash diversions at the tax equity partnership level are of the utmost importance to the lenders.

The most common cash sweep is for unpaid indemnity claims. The market has generally moved toward a 50% or 75% cash sweep for unpaid indemnity claims. This means that 50% to 75% of the cash that would otherwise be distributed to the sponsor partner would instead be swept to the tax equity investor to cover any unpaid indemnity claim. However, some tax equity investors still require a 100% cash sweep. The risk profile of a given project may also lead to a high cash sweep percentage.

A 100% cash sweep is never acceptable to the lenders because this could leave the sponsor partner with no funds to service the holdco debt. If the cash sweep percentage does not leave enough money to service the debt, then there must be another feature to protect the lenders, which can come in the form of a guarantee from the sponsor if the sponsor is creditworthy, another form of credit backstop, or a cash-backed letter of credit that can be drawn by the lenders.

Another cash sweep that has become more important since the November election is a cash sweep for failure to flip by the target flip date. This would only occur in a partnership flip transaction that is yield based rather than time based. If the flip does not occur by a target date, then most or all of the cash after that date may be swept to the tax equity investor. If the debt matures before the target date, then this cash sweep only concerns the lenders to the extent there is a chance the project will underperform and the debt maturity will be extended past the target flip date.

Transfer restrictions

The lenders’ most important collateral during the term loan is the interest the sponsor partner holds in the tax equity partnership. Consequently, the ability to foreclose on and subsequently transfer this collateral is extremely important because the sale of this collateral may be the only way for the lenders to recover their investment after a default.

Tax equity partnership agreements restrict changes in control of the sponsor partner without tax equity investor consent. There are extensive transfer provisions in every partnership agreement with which lenders must comply in a foreclosure or subsequent transfer after foreclosure.

Tax equity investors generally take one of two approaches with respect to lender transfer provisions. The first approach is to view lender transfers no differently than any other transfer of the sponsor interest in the tax equity partnership. Under this approach, lenders generally have to satisfy the same requirements that the sponsor would have to satisfy if it were to transfer its interest in the tax equity partnership. Some tax equity investors will make minor accommodations for the lenders.

The second approach is to write a separate set of transfer provisions specifically governing a lender foreclosure and subsequent transfer. Under this approach, the transfer restrictions are generally relaxed for a lender foreclosure and subsequent transfer compared to other transfers of the sponsor interest in the tax equity partnership.

There are still extensive negotiations around the details in either case. In situations where there are no special lender transfer provisions written into the tax equity documents, a smart sponsor usually insists that the tax equity investor consent in advance to a change in control after a default on the holdco debt. The main issues come down to the financial tests that must be satisfied by the entity the lenders use to foreclose and any subsequent transferee as well as what experience the subsequent transferee must have operating the types of projects involved.

Forbearance

Even with a holdco loan, there may still be forbearance issues between debt and tax equity if the lenders expect to retain project-level collateral until the project reaches commercial operation.

The tax equity investor must be a partner for tax purposes before the project is placed in service in order to share in any investment tax credit on the project. A utility-scale project is usually considered placed in service when it reaches substantial completion under the construction contract. Tax equity investors in solar projects, on which investment tax credits are claimed, usually stage their investments. They invest 20% before the project is placed in service and 80% after.

The lenders may still be holding a security interest in the project directly until the 80% investment is made.

Some tax counsel may not allow the lenders to hold a security interest in the project directly during this interim period because it looks like the sponsor to still treating the assets as if it owns them directly.

If the lenders still have a direct security interest in the project assets, a debt default could lead to the lenders taking the assets. This possibility leads to a tense negotiation over whether tax equity has the ability to cure the debt default and under what circumstances and for how long the lenders must forbear from exercising remedies.

One approach taken in some deals is for the lenders to be given the right to buy out the tax equity by repaying the tax equity the amount of their investment. However, this may be viewed as an unwind that calls into question whether the tax equity investor is really a partner during the period its investment may be unwound in this fashion. In some transactions, the tax equity investor proceeds have been placed into an escrow account and can be used to repay the tax equity when it is bought out by the lenders. Any such escrow would have to belong to the sponsor and the interest earned on the account reported by the sponsor as income. Even then, the arrangement may be viewed as not a real investment by the tax equity investor until the escrow is released. Other steps can be taken to reduce this risk.

Tax reform

Congress is expected to reduce the corporate income tax rate and make other changes in the US tax code, although when this will happen is unclear.

There are two potential effects on holdco loans.

One is the effect on the actual tax benefits claimed in renewable energy projects, like tax credits, depreciation and interest deductions.

The other effect is a change in the federal corporate income tax rate.

The timing of any tax reform complicates any analysis.

Most of the market believes that Congress is unlikely to alter the current timetable for phasing out production tax credits and investment tax credits for renewable energy projects. Production tax credits are already being phased out and the investment tax credit for solar is scheduled to start phasing out after 2019. (For more detail about the phase outs, see “Tax Credits Teed Up For Extension”.)

If the tax credits were to be changed before the tax equity funds, then it could be grounds for the tax equity not to fund or lead to a lower tax equity investment. Either way, there would be a hole in the capital structure that would have to be filled. If the sponsor does not contribute additional equity, then there would be a default on any construction debt.

A reduction in the future value of production tax credits, which are claimed over 10 years, could reduce the amount of the term loan if production tax credits are taken into account in sizing the term loan. To the extent the tax equity investor does not have tax credits to help it reach its flip yield, then it will need to draw on more cash to do so. Many term lenders are not sizing debt based on potential tax changes.

A reduction in the corporate tax rate would have two effects on holdco lenders.

The first is an effect on the broader renewable energy financing market. If corporations in general are required to pay less in taxes, this could lead to a smaller tax equity market, which could lead to increased tax equity yields and fewer projects getting financed. However, a reduction in tax rates would probably not reduce the amount that the largest tax equity investors have available to invest.

The more immediate impact on holdco lenders is a reduction in the value of depreciation deductions that are a significant portion of the tax equity return. A dollar of depreciation is worth 40% more at a 35% tax rate than at a 25% tax rate. This affects both production tax credit and investment credit deals because both types of transactions rely on depreciation as a source of tax equity return.

The timing of a change in corporate tax rate is important. A change in the tax rate before or soon after a project is placed in service is more likely to reduce the amount of tax equity financing that can be raised. A change after a project has been operating for a while is more likely to accelerate the flip date and leave more cash to service back-levered debt. (For a more complete analysis, see “The Market Reacts to Possible US Tax Reforms” in the February 2017 NewsWire.)

A separate tax change issue that occasionally comes up during negotiations is a provision that increases the amount of cash distributed to tax equity if there is a change in tax law that slows future depreciation. This is not a common provision and is the result of a proposal by former Senator Max Baucus, who stepped down as chairman of the Senate tax-writing committee to take up the post of US ambassador to China in February 2014, to move to “pooled” depreciation. Under pooled depreciation, all equipment would be put into one of four asset pools. Each year, a company would deduct a fixed percentage times the aggregate unrecovered cost of assets in the pool. Any new capital spending on equipment during the year would be added to the pool. The change would have affected existing assets.

The Baucus bill would have slowed depreciation. Senator Ron Wyden (D-Oregon), who replaced Baucus as the senior Democrat on the tax-writing committee, introduced his own pooled depreciation bill in 2016 that would have accelerated depreciation of renewable energy projects. (For earlier coverage, see “US Tax Changes Start to Take Shape” in the December 2013 NewsWire and “Wyden Proposes Depreciation Revamp” in the June 2016 NewsWire.)

Other items

The US government will move to assessing partnerships directly for any back taxes the partners are found to owe after a partnership audit starting in the 2018 tax year. The Internal Revenue Service is tired of chasing partners for these taxes.

Holdco lenders are interested in how the IRS implements the new system. In particular, partnerships can elect one of three or four alternative procedures under the new rules. If the tax equity partnership is responsible for paying taxes that the tax equity investor should have paid directly, it would reduce the amount of cash available for distribution to the sponsor partner and potentially leave too little cash to service the back-levered debt.

Many lenders require the partnership “push out” any tax liability to the partners directly by making an election under section 6226 of the US tax code. The election causes audit adjustments to be the responsibility of persons who were partners in the tax equity partnership during the tax year under audit.

Most Holdco loans have a tenor of around seven years, but tenors can range from five to 10 years.

Some holdco loans fully amortize. Others have a bullet payment due on the maturity date, which would typically require a refinancing. In all cases, these variables are determined by the financial model.

The pricing of holdco loans is mostly in the range of LIBOR plus 2% to 3% currently. The variations in pricing are typically based on the perception of risk, which includes variables such as sponsor experience, counterparty default risk and the result of negotiations with tax equity. Some start as low as LIBOR plus 1.75%, but this requires an exceptionally strong financial profile. In addition, the margin typically increases between 12.5 and 25 basis points every three or four years to encourage repayment as quickly as possible.