Islamic Bonds Go Mainstream

Sukuk or Islamic bond financing still has the reputation of being a niche product. Despite this, it is showing signs of becoming a mainstream option to finance infrastructure projects.

The origin of the niche product comes from the fact that sukuk are inherently an alternative. Sukuk permit bond-like financings to be structured in a way that is compliant with shari’a law. (The singular form is sakk, meaning certificate.) With the growth of Islamic finance generally, sukuk generated a significant amount of interest in the early to mid-2000s, but suffered a decline after the twin blows of the worldwide financial crisis and the influence of Islamic scholarship that criticized the structures used at that time for their lack of adherence to Islamic principles. As markets have slowly recovered, interest in sukuk is once again growing.

This article describes what sukuk are, who is interested in them, how typical sukuk that might be used in project finance are structured, some inherent risks and mitigation mechanisms and key trends to watch.

Among recent developments of note, a consortium of two Australian solar companies announced that it will fund the first 50 megawatts of a planned 250-megawatt solar project in Indonesia entirely through sukuk issued in Malaysia that will include construction financing. Also of interest to the market is the joint venture between Saudi Aramco and Total that successfully launched sukuk financing with a 14-year tenor for the greenfield development of the Jubail oil refinery in Saudi Arabia. In April this year, Sadara Basic Services Company issued 15.75-year sukuk that were equivalent to US$2 billion in size to finance part of the development of a chemical and plastics production complex in Saudi Arabia.

These changes come at an opportune time. The Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) nations have a large pool of underutilized sovereign capital. Islamic finance structures are an obvious fit for the region. There is a confluence of a generally-acknowledged need for infrastructure development and increasing political support for the development of Islamic finance as an alternative to conventional finance. The Emirate of Dubai in the United Arab Emirates has recently launched an effort to develop a vibrant sukuk market to rival those of financial centers with a longer track record of sukuk — particularly Malaysia and fellow GCC member Bahrain.

To date the absolute number of sukuk issuances remains a small proportion of bond issuances. But with some peaks and troughs, the trend is generally upwards. Issuers claim that recent sukuk issuances have been heavily oversubscribed — in some cases by as much as three and a half times — and that it is a lack of offerings that is holding up the market, not lack of demand.

Interest in Sukuk

Islamic investors with a mandate to invest in investment opportunities that comply with Islamic principles are the most obvious market for any Islamic product. But Islamic investors are by no means the only market for sukuk issuances. Issuers report that conventional investors have shown an appetite for sukuk. The most cited reason is that sukuk offer a means of diversification. Some conventional holders report being comforted by the fact that the Islamic banks who invest alongside them tend to hold their investments until maturity, creating a more stable investment for everybody else.

So-called ethical investors are an additional pool of liquidity that may be attracted by sukuk. Because of shari’a compliance requirements, sukuk can only be issued for projects that meet ethical standards including for purposes that include some degree of public good. While those standards are grounded in Islam, there is often a coincidence with the goals of more secular ethical investors. Another group who may become comfortable with sukuk are traditional project financers and developers.

Sukuk are an asset-based financing structure, so they share a risk profile that in certain respects is reminiscent of equity investments, including “tax equity” finance widely used in the United States. International investors will find them more familiar than might be expected.

A final point worth emphasizing is that there is nothing inherent in a sukuk structure that limits its application to countries with large Muslim populations or that have a tradition of Islamic law. These structures can be implemented for projects located anywhere.

What Sukuk Are

Like a bond issuance, sukuk are a way to securitize lending. In fact, the sukuk are only part of the overall structure. They are the part of a transaction that is used to securitize underlying Islamic finance structures. This is why sukuk come in a variety of flavors such as the ijara sukuk or musharaka sukuk described below. However, while it is common to call sukuk Islamic bonds, doing so can be misleading. There are similarities, but also a number of important differences between the two types of instruments.

In its simplest terms, a bond is a form of debt and represents a sophisticated IOU. In exchange for advancing a share of the principal, the bondholder is entitled to interest (the coupon) and also the repayment in full of the principal amount of the bond. Both the fact that a bond represents a debt and there is a payment of the coupon offend key principles in Islamic finance. Islam forbids treating money as a commodity with inherent value that can be traded at a profit. Rather, Islam regards money as no more than an exchange mechanism for other goods and services. Because of this, the payment of interest (the Arabic term is riba) and the selling of debt for interest are not permitted.

In contrast, instead of representing a debt, a sakk represents an undivided beneficial ownership interest in a physical asset being financed. Because a sakk is an undivided share of an asset, the holder of the sakk can receive a portion of the income generated by the sukuk asset as his return. This, rather than an interest payment, is the incentive to invest. This ownership should also be distinguished from equity financing. The sukuk holder does not own any part of a company, and neither are the sukuk assets available to be sold in the event of non-payment.

Other basic similarities between sukuk financing and conventional bond financing include the payment of principal at maturity (even though in a sukuk this may be achieved in a somewhat roundabout manner). Sukuk also feature issuing mechanics that are based on and in many cases are identical to conventional bond issuances.

A sukuk issuance will include a rating of the issuer, usually by a conventional bond rating agency using completely conventional bond financing methodologies. Like some bonds, overall rating of a sakk is generally the same as the ultimate sponsor since the sukuk are generally issued by a special-purpose vehicle that will not have an extensive operating history.

There will also be a prospectus that is little different from a conventional bond prospectus. Like a conventional bond issuance, there will usually be a roadshow by the issuer. Sukuk are typically listed in well-established bond markets such as London, Dublin or Luxembourg, although other jurisdictions such as Dubai would very much like to change this. Because of the strength of the Malaysian market in sukuk, it is common to see sukuk issued in Malaysian ringgits. Dollars are also common, but the currency used is deal specific and not critical. To the extent that sukuk can be traded on a secondary market, those trades will occur in a conventional manner. Finally, sukuk are subject to the same securities regulations that apply to conventional instruments issued in the same markets.

Although riba is not permitted, it is permitted for the sukuk holders to receive a return deriving from their beneficial ownership of the sukuk assets. The return paid to the sukuk holders does not have to be the entire income generated by the asset. The issuer and the holder can agree to send some of the income to the holder of the sakk, and some to the issuer. They can even agree to benchmark the return to some widely-known index such as LIBOR.

Permitting a benchmark is subject to some restrictions. The sukuk issuer may not promise to pay the entire benchmarked amount regardless of actual performance of the sukuk assets. If the income from the asset is insufficient, then the payment to the sukuk holder will not be the amount that might have been predicted. This may seem like a severe restriction that significantly increases risk to the holders. However, the restrictions placed on the certainty of a return have an inherently mitigated impact where the income of the project can be predicted with accuracy — for example, because the project is a power project with a long-term offtake agreement. In addition, many shari’a boards will permit mechanisms to a degree to enhance the credit of the issuance. These may include debt service reserve accounts that can be drawn upon in the event of insufficient cash from the sukuk assets to pay the return and sometimes also a payment guarantee, provided that the guarantor is a third party.

Perhaps surprisingly, sukuk usually provide for the payment of default interest just as would a conventional bond. The apparent contradiction is reconciled by provisions requiring that default interest that is charged will not actually be paid to the sukuk holders. Rather, it will be given to charity.

One addition to these largely conventional features is a feature unique to Islamic finance. Sukuk will be vetted by a shari’a board for compliance with shari’a principles. This board is appointed by the bank that is structuring the sukuk, and the composition of the board will be disclosed to investors. The shari’a board will examine the structure of the sukuk and opine on whether it meets that board’s shari’a compliance standards. This will include an examination of the nature of the underlying business or project being financed. Certain endeavors such as those involving alcohol, pork, gambling and obscenity may not be financed by sukuk — or any Islamic finance for that matter. The ethical goals of the sukuk will also be examined. Infrastructure projects often have a high degree of social utility and so they can be an excellent fit in this respect.

One problem of which an investor should be aware is that sukuk have been subject to different opinions among Islamic jurists about what is and what is not permissible within a structure. The Malaysian market has been criticized for what some influential scholars perceived as an overly liberal approach. An investor will want to examine the reputation of a particular board, and some investors may choose to conduct their own shari’a review. The shari’a board’s evaluation of an issuance does not form a part of the bond rating.

In some jurisdictions, prevailing tax treatment may make sukuk less tax efficient for the issuer than conventional bonds. This is because the periodic distributions under sukuk may be treated as non-deductable distributions whereas interest payments are generally deductible. A number of countries with vibrant financial centers have addressed this imbalance by legislation. These include the United Kingdom, Singapore and Luxembourg. A notable exception is the United States tax code, which has not been changed to accommodate sukuk.

There are a number of basic types of sukuk structures. Each of them is based on an underlying Islamic finance structure. The “sukuk” aspect is the element of securitization that is layered on top of one of these structures (or a hybrid of more than one). The structures are chosen depending on the nature of the activity being financed and to a large extent the preference of the issuer or the perceived appetite of the market. Within general parameters, significant degrees of innovation and customization are possible.

The most common sukuk that are readily adaptable to project finance are the ijara (or leasing) sukuk and the musharaka (partnership) structure. Of these, an ijara sukuk is the most common.

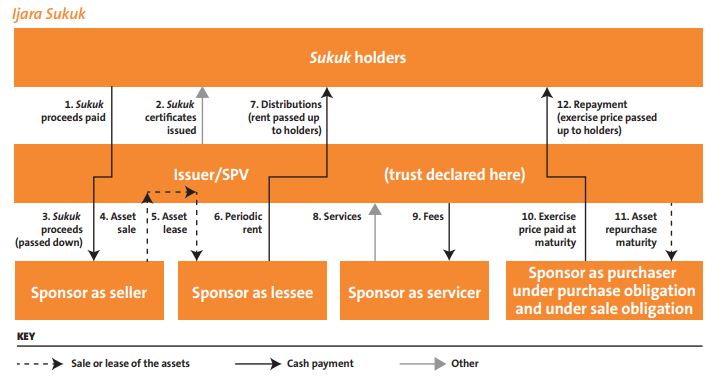

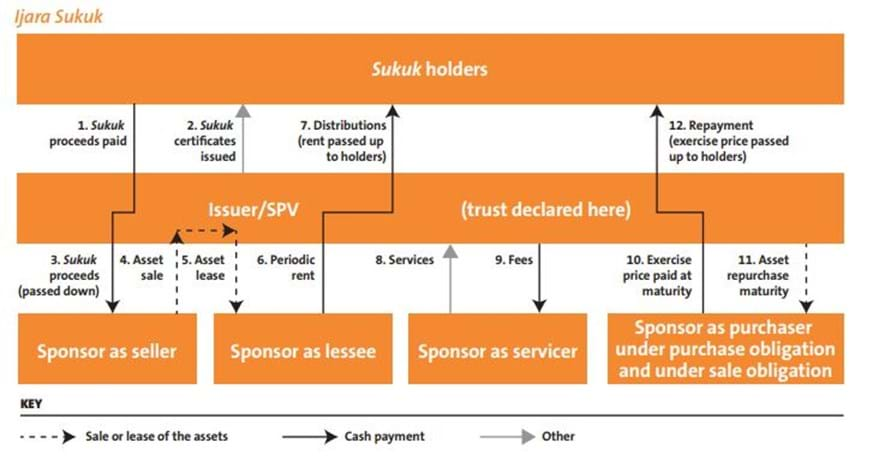

Ijara Sukuk

The basic steps and key documents for a typical ijara sukuk are shown in the diagram to the left.

A special-purpose entity or SPV is established, and each holder contributes cash to the SPV in exchange for its sakk.

The sponsor sells assets to the SPV and receives in return the proceeds of the cash contributed by the sukuk holders. The SPV declares a trust over the assets and becomes the trustee acting for the sukuk holders. The trust is typically granted under English law.

The SPV pays the cash to the sponsor as contribution for the purchase of the assets. The cash may be used for the purposes of the sukuk.

The SPV then leases the assets back to the sponsor.

The SPV enters into a separate purchase obligation agreement, a sale obligation agreement and an asset service agency agreement with the sponsor. These agreements have the following features.

The purchase obligation agreement obligates the sponsor to purchase the assets back at maturity or (at the option of the holders of the sukuk) on an event of default. The purchase obligation in the case of an event of default is in lieu of a direct right by the sukuk holders to liquidate the sukuk assets.

The sale obligation agreement permits the sponsor to purchase the sukuk assets for an agreed price equivalent to the face amount of the sukuk certificate plus any remaining unpaid periodic distribution amounts upon certain events, which typically are tax events.

The service agency agreement provides for the sponsor to manage the sukuk assets and the trust. Insurance obligations may be shifted from the SPV trustee to the sponsor (as lessor of the assets) through the service agency agreement.

In some ijara sukuk, there may also be a substitution undertaking agreement to allow the substitution of sukuk assets that must be sold or that wear out. The replacement assets must have no less than the same value and ability to generate revenues.

During the rental period, the sponsor, as lessee, makes rental payments to the SPV rather as would be done in a conventional sale-leaseback. These rental payments are intended to be sufficient to pay periodic distributions to the sukuk holders. The payments flow through the SPV as back-to-back payments.

The end of the lease period and dissolution of the trust coincide with the maturity of the sukuk. The sukuk assets are purchased back by the sponsor pursuant to the purchase obligation agreement. The purchase price, which is generally the face amount of the sukuk certificate plus any remaining unpaid periodic distribution amounts, is passed on to the sukuk holders, repaying their principal.

For shari’a compliance reasons, the assets held in trust must generally both be existing assets and ones that will not be consumed during the lease period. If the assets cannot be identified at the time they enter the trust, then the sukuk will not be salable on the secondary market except at par. This creates a problem in projects that are in their construction phases. Some transactions have allowed an ijara sukuk to be combined with an istisna’a contract and have permitted trading on the secondary market once the percentage of identified assets reach some threshold — generally 30%. An istisna’a contract is a contract whereby a supplier or construction contractor agrees to manufacture certain identified goods (such as a project) in exchange for staged payments. (For further reading on istisna’a project financing structures, see Keenan, Richard, “Islamic Project Finance: Structures and Challenges,” in the February 2010 Project Finance Newswire.) Sakk in an ijara sukuk will be saleable on the secondary market for a profit once the asset becomes existent or identifiable.

With that tradability caveat, an ijara sukuk structure is sufficiently flexible to be used to finance a pool of assets acquired over a period of time, such as, for example, a pool of distributed solar projects where individual installations would be acquired over a period of time with periodic investments by the sukuk holders to finance the acquisition and installation of the projects as they enter the pool. This is done through a master ijara (or master lease) agreement where contribution, purchase and lease take place periodically as assets are acquired. This is very similar to master lease agreements that have been used in the United States as part of tax equity transactions for distributed solar projects.

Musharaka Sukuk

Another sukuk form is a musharaka, or partnership sukuk. Until a few years ago, this was a popular structure widely regarded as being particularly suitable for project finance because it closely replicated the risk profile of more conventional bond structures. Unfortunately, it so closely replicated them that it later came under severe criticism for being not shari’a compliant. Since that time, it has lost a great deal of the popularity it once enjoyed and is now much less likely to be used than an ijara sukuk. Nevertheless, certain recent transactions like the aforementioned financing of the Jubail oil refinery in Saudi Arabia have used this structure.

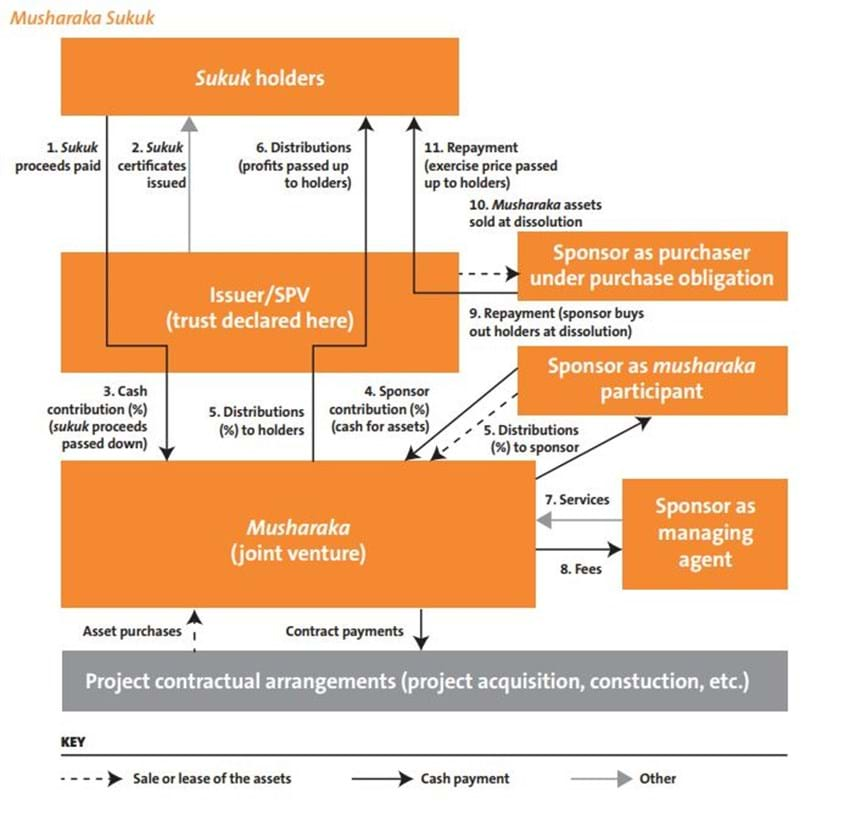

The basic steps and key documents of a typical musharaka sukuk are shown in the diagram above.

The venture is established as a musharaka, which is a joint venture typically between two parties — the trustee as partner and the sponsor as managing agent. A musharaka does not have to be (and frequently is not) a formal partnership entity. It can be established contractually. The sponsor generally manages the joint venture and can charge a management fee if there is a separate management agreement, although any such management fee is generally quite nominal.

An SPV is established to hold the sukuk holders’ interests in the musharaka.

Sukuk holders’ contributions come as contributions to the SPV in exchange for the sukuk certificates. The SPV declares a trust over the proceeds and any assets acquired with them. Like the trust in an ijara sukuk, the trust is conventional and is usually formed under English law.

The SPV contributes the proceeds from the sukuk to the musharaka. The sponsor also makes a contribution to the musharaka. The contribution cannot consist solely of debts. Each of the SPV and the sponsor receives a proportionate number of units of the musharaka in return. Their respective investments in the musharaka partnership are used for the purposes of the musharaka — for example, to construct, develop and own a project.

The musharaka can include contractual arrangements to construct a project. These would generally be Islamic compliant financing arrangements, such as an istisna’a contract arrangement.

The musharaka participants may make their contributions over time, for example, as phased payments to build a project.

The musharaka participants share profits of the musharaka in an agreed proportion. The agreed portion that is returned to the issuer SPV is usually calculated to be sufficient to pay the periodic distribution amount that is paid by the issuer SPV to the sukuk holders. The agreed proportion does not have to be the same as their contribution proportion.

In contrast to profits, losses are shared strictly in accordance with the amount contributed. However, a musharaka structure is like a partnership in that there can be circumstances where there is not enough profit generated to make this return guaranteed.

On maturity of the sukuk, or (at the option of the trustee acting on instructions of the sukuk holders) upon an event of default, the musharaka is dissolved. To provide for the return of the investment to the sukuk holders, the sponsor purchases the musharaka assets at an agreed exercise price.

Both the payment of distribution amounts and the exercise price for the repurchase option are at the heart of the controversy that has surrounded the musharaka structure.

A musharaka is explicitly a joint venture and so inherently it ought to be capable of losing money as well as earning money. This would not be the case in a conventional bond, and so structures were devised to remove this feature as much as possible. Prior to 2008, it was common for musharaka sukuk transactions to include a number of mechanisms that largely eliminated these risks so that the transaction behaved from the investors’ point of view very much like a conventional bond. The sponsor (as managers) committed to make interest loans to the investor partners at times when the venture did not have sufficient profits to pay the periodic distributions to the sukuk holders, thus protecting the periodic distributions from most shortfall events. The sponsors also committed to repurchase the sukuk assets at maturity for the face amount rather than the prevailing market price, which, in the case of a failing project, could be less than the amount of principal advanced by the holders.

In 2008, both of these mechanisms were criticized for being inconsistent with the concept that a musharaka is a joint venture. Loans that guaranteed the periodic distribution regardless of profitability made a musharaka indistinguishable from a bond with interest payment obligations that do not depend on profitability. A binding promise by the sponsors to repurchase the sukuk at the face amount rather than the prevailing market value also removed functional risk of loss of principal. This criticism had an immediate practical effect because spearheading it was the chairman of the Islamic board of the Bahrain-based Accounting and Auditing Organization for Islamic Financial Institutions, which is usually abbreviated to AAOIFI and happens to be the organization that accredits many sukuk. With these mechanisms no longer permitted, interest in the structure plummeted.

One form of musharaka that is still commonly used is the diminishing musharaka. To date, this structure is mostly confined to the residential housing market, but it could be applied in project finance. In a diminishing musharaka, the sponsor party makes periodic payments to the sukuk holders over the life of the sukuk. In this way, the ownership of the sukuk assets by the holders diminishes steadily with each payment, rather than all at once on a maturity date as in a conventional musharaka. Unlike conventional lending, however, the obligations and benefits with respect to the sukuk assets also shift along with the shifting ownership. Thus, the return that is paid in the form of periodic distributions will diminish as the holders’ stake in the assets that generate the return reduces.

Mitigating Risks

Like conventional bonds, sukuk holders may not be comfortable taking construction risk. Therefore, sukuk are sometimes created as refinancing arrangements for a project that was financed conventionally during the construction phase. On the other hand, some recent sukuk have financed construction using risk mitigation such as robust EPC arrangements and guarantees by third parties. However, these guarantees have been limited to those provided by governments.

The fact that the market still desires a government guarantee is perhaps more a feature of the relative immaturity of the market than anything inherent to sukuk as a structure. As the market develops, it can reasonably be expected that other third party guarantees will be accepted. Regardless of who gives them, these third party guarantees should be carefully distinguished from the guarantees of return by the issuer that were a problem in musharaka sukuk. The issuer cannot guarantee the return of the sukuk investors because such an undertaking would be economically identical to a promise to pay interest regardless of the performance of the project being financed. But it is possible for a bona fide third party to do so, provided that the guaranty obligation is separately documented and voluntary in nature.

Just as in conventional project bonds, a practical issue that makes construction phase sukuk financing difficult is the higher likelihood that a project will need to obtain covenant waivers. Bonds and sukuk holders equally are traditionally reluctant to get involved in day-to-day issues, and obtaining consents can be difficult, especially when the project may need a rapid response. This can be mitigated by carefully drafting covenant packages to account for issues that may emerge during construction and providing more leeway for a single agent to make decisions without requiring the full holder group to issue the waiver or consent.

Other issues to be aware of are somewhat unique to sukuk. These are flagged in the prospectus just as would be done in conventional bond financing. Prospectuses will caution that the returns generated by the sukuk are generated by the sukuk assets and, therefore, if the assets do not generate income (for example, because they are destroyed), no return or periodic distribution may be forthcoming. Prospectuses also generally caution that a secondary market may not be available, so sukuk holders may not be able to liquidate their positions as readily as they could on the conventional bond market.

There are two issues at play here. One is mainly a function of the relatively small size and novelty of the sukuk market and, in time as new listing venues appear, this may diminish. The other is that, in some cases, shari’a compliance rules would forbid the trading of sukuk. Such restrictions should be disclosed in the prospectus.

A more significant market problem that has hindered the use of sukuk for project finance, but that will not be identified as risks in the prospectus, is that sukuk have typically had a maturity that has typically hovered around five to seven years. This is not a theoretical limit; it has simply been the longest maturity with which investors have previously been comfortable. However, it is usually not a good fit if the project being financed has a power purchase agreement with a typical 20-year term. Conventional loan financing has long been comfortable with tenors that more closely approximate the income generating life of the project, and so this makes sukuk less attractive. Happily for those interested in financing using sukuk, there are market indications that this barrier is increasingly being broken with some sukuk issuances having tenors as long as 15 years. It is not unlikely that longer tenors will emerge if perhaps initially only for the more robust projects and issuers.

Another issue that a prospectus will not mention is that sukuk have also been criticized for being somewhat document intensive. To some extent, this is unfair. For shari’a compliance purposes, some obligations of a sukuk structure are broken out into separate undertakings, frequently of a unilateral nature. This adds some apparent complexity, but it may not actually add significantly to the true complexity of a transaction. Nevertheless, it remains fair to say that, as a relatively new structure with complex requirements, issuers are more likely to find themselves breaking new ground in a sukuk than a conventional structure such as an interest-bearing loan. This can result in somewhat higher transaction costs. Over time, it is expected that documentation and shari’a board requirements will both become more standardized and this will inevitably bring transaction costs down.

Security issues in sukuk are much closer to a bond than a conventional loan, and the assets on which the sukuk have an undivided beneficial interest cannot be foreclosed upon. For this reason, sukuk are said to be asset based, but not asset backed. The holders’ remedies for non-payment are limited to guarantees that may have been provided and to contractual remedies. On the other hand, the fact that sukuk assets are held in a trust by a special-purpose entity means that those assets are protected from bankruptcy claims against the sponsor, giving a somewhat lower risk profile than a conventional corporate bond issuance.

A related issue is the need for the holders to protect the assets. Without assets, the sukuk will generate no revenue. Insurance is therefore critical just as it is in project finance generally. This could be conventional insurance, but conventional insurance is not favored in Islam because it is considered to be a species of gambling (more technically called gharar, which conceptually refers to excessive risk). Therefore takaful Islamic insurance products may be used in preference to conventional insurance. A takaful insurance product is a cooperative risk allocation pool where members donate to a fund from which payments can be made when a member encounters a defined loss. It, therefore, provides a means for compensation without the speculative element that makes conventional insurance repugnant to Islamic finance principles. As in project finance, the obligation to procure insurance can be shifted first to the SPV, and then it can be further shifted to the sponsor.

In theory, if a transaction is declared to be not compliant with shari’a law, the transaction could be considered void from an Islamic point of view even if the closing of the transaction has occurred. However, even if this happens, the contracts that make up a sukuk structure will not be invalidated, and the deal itself will not be unwound. The contracts that make up a sukuk transaction are generally governed by a well-established body of law such as that of England or New York, and contract interpretation and enforcement are no different from any other contract under those bodies of law.

Trends to Watch

At the present time, sukuk are far from being the default financing mechanism in any market, but sukuk are already an available alternative. In any growing financing market, the volume and size of deals are trends that are important to watch as an indication of market trajectory. However, perhaps an even more important measure of the development of this market is who is doing the issuing. As the sukuk market matures, we would expect to see a shift from issuances almost exclusively by large governmental or quasi-governmental entities to smaller or more purely private sector issuers. We can anticipate that this will begin first with international project developers with a strong track record. There are some indications that this is beginning, and from the perspective of international developers and potential investors alike, it is a key issue to watch.

A second trend to watch is the increasing maturity of issuances. As maturities extend, sukuk become increasingly suited to finance projects. Until maturities routinely approach those of conventional loans, many projects will be unable to finance using sukuk structures.

Another trend worth monitoring is the increase in political support for sukuk issuances. Some of this has already occurred. Malaysia has been the most aggressive jurisdiction in fostering a vibrant sukuk market, followed closely by Bahrain. The willingness of countries with influential financial centers such as the United Kingdom to adjust their laws to level the playing field between sukuk and conventional bonds is a significant indication that sukuk are taken seriously in those countries. Dubai’s announced goal of becoming a global center for sukuk represents another significant development. Many believe that a regional market would make it easier to attract capital from other Gulf states. It is also hoped that these trends will increase standardization of sukuk issuance rules.

This brings us to a final trend to watch, and it is one that is maybe a little counterintuitive if you read the press releases that often follow a successful closing. Highly bespoke and difficult transactions make for good war stories, but they are a barrier to the expansion of the sukuk market as a whole. As sukuk become more common and more familiar, we can look forward to more frequent and routine transactions that break less ground and generate less fanfare.

In the meantime, sukuk are already a practical alternative financing technique that can attract significant pools of liquidity. Perhaps they are a niche now, but the signs are sukuk are going mainstream in the project finance market.